The smallest country in South America, particularly its capital of Montevideo, became an important destination for German-speaking Jewish émigrés to Latin America during the 1930s and 1940s. The country’s comparatively welcoming immigration laws and tradition of liberalism enabled around 10,000 German-speaking Jews to find refuge in Uruguay. The locals’ tolerant attitude to the refugees gave rise to various institutions, which paved the way for the newcomers’ integration into Uruguayan society. Some of these institutions still exist today.

Uruguay was not the destination of choice for most Jews fleeing Nazi Germany after 1933. They came there, simply enough, because the small Latin American country had granted them entry visas. Many had never even heard of Uruguay before. Given the shortage of basic information and news, German Jews had assorted preconceptions about this country of refuge. For example, the director and screenwriter Peter Lilienthal (1927–2023), who escaped Berlin with his mother at the age of eleven and arrived on a tourist visa in early 1939, had expected not only palm trees and the ocean, but also crocodiles, snakes, and elephants.

To enter Uruguay legally, a foreigner needed a travel permit or visa issued by a Uruguayan consulate, a certificate of good conduct from the police, a certificate of good health, and proof of funds amounting to 600 Uruguayan pesos, to be deposited at the national bank. After three years in the country, immigrants could apply for entry visas on behalf of their children, parents, and siblings – a provision that would save many lives.

Most émigrés were pleasantly surprised by Uruguay’s temperate climate. Montevideo, home to about 750,000 people at the time, was the urban center of a sparsely populated country with a total population of roughly two million. The structure of the city, with its irregular grid layout, well-developed infrastructure, and manageable size, made it easy for newcomers to get their bearings.

The lion’s share of residents were of Spanish or Italian descent, but there were also immigrant communities from nearly every European country – including Ashkenazi Jews from the (erstwhile) Russian Empire and Sephardi Jews from the Mediterranean region. Montevideo was also home to a ‘German colony’ numbering around 6,000 to 7,000 people. The Deutsche Schule Montevideo (German School of Montevideo) was founded as early as 1857. Uruguay had longstanding economic ties with Germany: its consulate general in Hamburg dated back to the mid-nineteenth century, and the Montevideo branch of the Deutsche Ueberseeische Bank (German Overseas Bank) predated the First World War.

However, Uruguay also felt the impacts of the global economic crisis of 1929. One reaction to the circumstances was the tightening of immigration regulations, which, unlike those of neighboring Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina, never explicitly discriminated against Jews. Another reaction was the coup d’état of 31 March 1933, led by the politician Gabriel Terra (1873–1942), which established a dictatorship with Terra as the new president. Ties to the Axis powers tightened: German companies such as Siemens were awarded major contracts in Uruguay and a branch of the NSDAP Auslandsorganisation (the Nazi Party/Foreign Organization) was established, attracting considerable support within the small German community. Only a few non-Jewish Germans sought contact with the Jewish refugees who shared their native language. Among them were the brothers Karl and Gustav Stapff (?–?), originally of Weimar, who jointly operated Carlos Stapff & Compañía, a business specializing in laboratory equipment. Gustav Stapff and his family had only arrived in Uruguay in 1936.

The Spanish Civil War of 1936 to 1939 changed the political climate in Uruguay. The seasoned politician Alfredo Baldomir (1884–1948) demonstrated political acuity by promising to restore democracy as a presidential candidate in 1938 and distancing the country from the Axis powers.

Passenger manifests from transatlantic ships show that around 250 émigrés entered the country in 1933 and 1934, including Fritz Rawak (1905–1975?), a young doctor from Gleiwitz (Gliwice), and the stateless Weissbraun family from Bremen. In 1934, Karl Weissbraun (1909–?) and Fritz Rawak, together with representatives of Uruguay’s Jewish communities, founded a Hilfsverein für deutschsprechende Juden (Aid Society for German-speaking Jews) to support the new arrivals. Their objective was to help refugees find jobs and become self-sufficient – an effort facilitated by extensive contacts in the Jewish Communities. The Hilfsverein also served free lunches. It was later incorporated into the German-speaking Jewish Community, which had been founded in 1936.

Roughly 200 Jewish émigrés arrived in Uruguay in 1935, and the figure was around 600 each year in 1936 and 1937. A strikingly large number of these were independent butchers and cattle traders, who had lost their livelihoods in small towns and villages in Germany due to the ban on kosher slaughter enacted in May 1933. At that point, the emigration process was still relatively straightforward to organize; even the transport of household goods in ‘lifts’ proceeded smoothly. This term referred to shipping containers used by Jews emigrating not only to Uruguay, but also to the Mandate territory of Palestine or South Africa.

Fig. 1: The ‘lift’ containing the possessions of the Wolff family from Dannenberg in Lower Saxony is sealed before shipment to Montevideo. Dannenberg, 1938; Stadtarchiv Dannenberg.

Most refugees arrived in Montevideo in 1938 and 1939, the peak years of emigration by German-speaking Jews in general, including the waves of escapees from Austria following the ‘Anschluss’ (annexation) of March 1938, from Austria and Germany after the November Pogrom that winter (also known by the German euphemism ‘Kristallnacht’), and from Czechoslovakia following the German invasion on 15 March 1939.

For the families of the men arrested during this period, time was of the essence. In the aftermath of 9 November 1938, it usually fell to women to arrange all the required documents and payments for emigration, including the ‘atonement’ payment (‘Sühneleistung’). In parallel, they arranged all the documents for visa applications, ship passages, transit visas, transport to ports, and the shipping of household goods.

In Uruguay, too, women often became the main breadwinners in the early years. The ordeals of escape and exile placed enormous strain on marriages and partnerships, often leading to separations and divorces. Only in recent years has historical scholarship begun to recognize the central role women played in building new lives in exile.

Despite all efforts, immigration to Uruguay did not always go smoothly. The influx of predominantly urban refugees following the November Pogrom, most of whom settled in Montevideo, triggered an antisemitic campaign by right-wing conservative groups. As a traditional immigrant destination, Uruguay had placed clear requirements on newcomers’ professional backgrounds, seeking agricultural workers in particular. Nationalist newspapers such as La Tribuna Popular ran articles agitating against Jewish immigration, warning of competition in the labor market, predicting the displacement of local businesses, and calling into question the Jewish immigrants’ ability to acculturate in Uruguay. At the same time, a new policy instituted by Foreign Minister Alberto Guani (1877–1956) sought to curb immigration, limiting the authority of consular officials to issue visas and primarily targeting corruption among diplomats. His circular, though not legally binding, led to the non-recognition of any visas that had not been confirmed by the Foreign Ministry. As a result, passengers from various ships were denied entry. In most cases, affected immigrants were ‘interned’ in boarding houses until Jewish aid organizations and community representatives found a solution. They signed guarantees to the Uruguayan state that the refugees would not become a burden, after which the newcomers were permitted to begin their lives in Uruguay. This also affected émigrés who had arrived with visas for Paraguay but were stranded in nearby Uruguay after Paraguay closed its borders to Jewish immigration on 1 December 1938. There are no records documenting how many refugees were ultimately deported back to Nazi Germany.

With the outbreak of the Second World War on 1 September 1939, emigration slowed considerably. Civilian ships no longer departed from German ports, and more and more ‘lifts’ were held up in Dutch and Belgian ports. Despite all the obstacles, some refugees still reached Montevideo. After Germany occupied the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France, the only remaining legal escape route was via the Soviet Union to Japan and from there to the Americas, including Uruguay.

A total of 503 German-speaking Jews reached Montevideo in 1941. Without financial support from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) in New York and the tireless efforts of the staff at the Hilfsverein der Juden in Deutschland (Aid Society for Jews in Germany) in Berlin, many of them could not have been saved.

Unlike Germany, where residents were and still are legally obliged to register their addresses, Uruguay did not enforce such an obligation or have an official address registry system for keeping track of residents. Once a person was inside the country, they could apply for a residency permit and, after five years, naturalize as a citizen.

In 1933, roughly 30,000 Jews were living in Uruguay, most of them in Montevideo. They included immigrants from previous waves who had arrived from the Russian and Ottoman Empires and Hungary since the late nineteenth century, grouped into three community organizations by region and language of origin: Comunidad Israelita del Uruguay (Hebrew Community of Uruguay, predominantly Yiddish speakers from Eastern Europe), Comunidad Israelita Sefaradí (Sephardi Hebrew Community, predominantly Ladino speakers from the Ottoman Empire), and Sociedad Israelita Húngara de Montevideo (Hungarian Hebrew Society of Montevideo, predominantly Hungarian speakers from Greater Hungary).

Members of these communities had established a number of institutions, including the Centro Comercial e Industrial Israelita del Uruguay, which offered business loans and job placements; the Banco Israelita del Uruguay, a mutual aid fund; and the Mutualista Israelita del Uruguay, an insurance company. These organizations supported their compatriots and also extended assistance to German-speaking Jews.

The major American relief organizations, the JDC and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), operated in Uruguay with their own offices and staff. Their representatives, such as Israel Israelsohn (?–?) of HIAS, were waiting when passenger ships arrived and assisted newcomers with the entry formalities, customs clearance, and the transport of luggage and household goods. Israelsohn helped arrange initial accommodation for new arrivals who were not greeted by relatives or friends. After the Hilfsverein was established, the Deutschsprachige Synagogengemeinde Montevideo (German-speaking Synagogue Community of Montevideo) was founded in 1936; it was later renamed in Spanish Nueva Congregación Israelita (New Hebrew Congregation, NCI), and the aid society was eventually integrated into its work.

The informality of community structures, the language barrier, cultural differences, and the Orthodox affiliation of the existing communities all led to the establishment of a separate German-speaking Community. Organized like the official Jewish Community (or Gemeinde) of a major German city, most of its members came from the Liberal/Reform German Jewish tradition. The appointment of the first rabbi, Gustav Rosemann (1912–?), was a somewhat controversial choice: Rosemann was Orthodox. Nevertheless, the NCI managed to remain Liberal/Reform despite a series of crises. In 1950, Fritz Winter (1914–2000), originally from Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), who had found refuge in Bolivia, was appointed the Community rabbi of Montevideo. As one of more than twenty Central European rabbis and cantors who arrived in Latin America before the war, he had studied in Berlin under Rabbi Leo Baeck (1873–1956). Under his leadership, the NCI began celebrating bat mitzvahs for girls in the 1960s. Today, it is Uruguay’s Reform/Liberal Spanish-speaking Jewish community and carries on the legacy of German-Jewish cultural heritage.

The NCI’s core responsibilities included safeguarding religious life and providing legal counseling to its members. In March 1937, the Chevrah Kadishah, or burial society, was established, and an agreement was reached with the other communities to share the Jewish cemetery in La Paz. To assist community members in need, the congregation joined the Asociación Filantrópica Israelita (the Hebrew Philanthropic Association, or AFILANTIS). AFILANTIS received significant funding from the JDC; without this support, the community’s social situation would have been much more precarious.

Georg Freund (1881–1971), formerly deputy editor of the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung in Berlin, oversaw the congregation’s bulletin. Its official bilingual title was Boletín Informativo – “Gemeindeblatt” Órgano Oficial de la Nueva Congregación Israelita de Montevideo (“Gemeindeblatt” Information Bulletin – Official Organ of the New Hebrew Congregation of Montevideo). Published in German, its content extended far beyond a typical newsletter of a Jewish Community and, for many, was the only available source of information whatsoever – that is, until the German-language radio broadcast La Voz del Día – Die Stunde des Tages (The Voice of the Day) was launched. The congregation’s bulletin often ran articles urging members not to speak German in public or while riding the bus, and not to walk in large groups along the beachfront promenade. It also sharply criticized anyone who frequented the café Oro del Rhin (Rheingold), perhaps out of homesickness for German culture: didn’t the readers know it was run by diehard Nazis?

At the end of 1938, the unitary German-speaking Jewish Community (Einheitsgemeinde) faced a serious crisis. Under trying circumstances, it had brought together Jews of diverse backgrounds and beliefs under one institutional roof. The large influx of new arrivals during the winter of 1938–39 and the reports of the horrors of the November Pogrom intensified questions about German Jews’ identity, the sense of acculturating into the mainstream of their country of exile, and their relationship to Germany. This raised the fundamental issue of whether there was still such a thing as another Germany – and whether members of the Community should openly invoke the idea of one. Then again, this entire debate was being conducted in German. The disagreements ran so deep that the board eventually convened a general assembly of the Community to resolve the matter. They invited external mediators: Israel Israelsohn, the HIAS representative in Montevideo, and the Rabbis Salomón Algazi (1919–1982) of the Sephardic community, and Aron Milevsky (1904–1986) of the Ashkenazic community. On 7 March 1939, the resolution was to maintain the unitary structure of the Community and to avoid any schisms.

By October 1940, the Community already had 1,241 registered members and households, representing about 3,800 individuals. To support the youth, Community members founded the Jüdischer Turn- und Sportverein (Jewish Gymnastics and Sports Association, ITUS) in 1938. Its constituent teams soon found success in mainstream Uruguayan sports – for example, the table tennis team became national champions for the second time in 1941. ITUS also served as a model for the establishment of the Macabi sports club on 9 June 1939, which exists to this day.

At first, for lack of language skills, many refugees had to earn a living through simple labor. University graduates sold ice cream on the beach or worked as bicycle couriers. In many cases, women, some of whom had never worked outside the home in Germany, were the breadwinners. Families whose furniture and household goods had already arrived could earn extra money subletting furnished rooms to boarders. In addition, women provided lunch services, mended clothing, or took on domestic work. Young girls often found employment as domestic workers or nannies in Uruguayan households, thus contributing to their families’ livelihoods, while boys began vocational training. For most young people, emigration marked the end of their formal education. This was typical not only in Uruguay, but also in other countries of refuge, including Mandatory Palestine.

Older émigrés who had completed courses at a business school in Germany often quickly found office jobs. Those with training in skilled trades were often able to get straight to work. Martin Levi (1921–2014), who arrived in Uruguay in 1937 at seventeen, after beginning training as an upholsterer in Germany, was immediately hired by the large furniture store Proxi Muebles. After just five years – and at only twenty-two – he set up his own business.

Most young people spent their free time entirely in the immigrant community, where they often met their future spouses. Only a few married locals. Thus escape, exile, interrupted education, and early responsibilities left marks on the lives of the second generation as well.

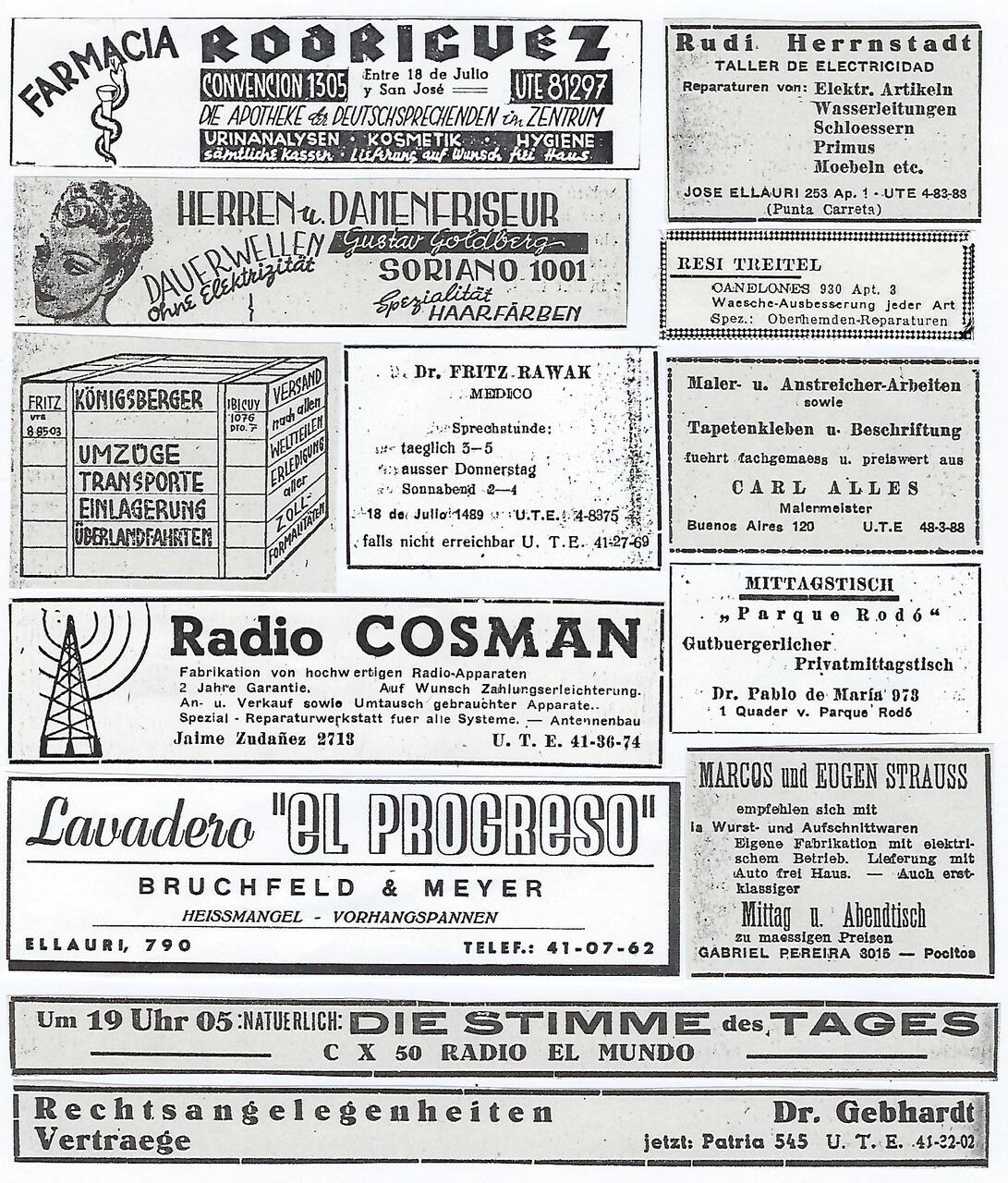

Among the many businesses founded during the early years were a large number of grocery stores. Newcomers depended on businesses where they could be understood and could buy familiar foods. One new concept – also popular with Uruguayan customers – were fruit and vegetable shops with appealing product displays. Additional businesses sprang up in the service sector: moving companies, transportation, legal counseling, and real estate, but also hairdressers and repair services for umbrellas, kitchen appliances, and watches.

Radio and photography shops were examples of technological transfer. Several businesses not only repaired radios but also sold units manufactured in house. Albert Maurer (1890–1969), formerly a theater director and co-founder of the acting troupe Die Komödie, earned his living with a photography studio. Other photographers also found success in Montevideo, including Jeanne Mandello (1907–2001) and her husband Arno Grünebaum (1905–1990).

A messaging service called El Rayo – Der Blitz (Lightning) – offered a way to leave messages that could later be picked up or delivered in person. Many advertisements, especially for repair services, serve as evidence that El Rayo was a widespread form of communication.

Fig. 2: A wide range of businesses and services were advertised in the Gemeindeblatt from 1938 to 1945. They targeted émigrés as potential customers, but also locals, as indicated by the use of Spanish; Copies in possession of the author.

To engage in self-employment, émigrés needed to be able to find suitable premises. In addition, their legal status had to allow them access to the market, the full legal capacity to conduct business, and legal security in contractual dealings. Such factors were often satisfied in countries with a history of welcoming immigrants, such as Uruguay. Another favorable factor was that most Jewish refugees arrived in Montevideo in a brief period, between approximately 1936 and 1940, and stayed in the capital city. As a result, a Jewish, German-speaking émigré community quickly took shape, which doubled as a market for numerous business opportunities. These new ventures had a clear advantage straight out of the gate: their shopkeepers and customers had a common language and came from similar backgrounds, which fostered trust.

Another form of self-employment was the traveling salesperson. Many succeeded in this field thanks to their expertise in a particular trade and because they offered a new kind of service. On their visits to businesses, they could show supplies they were selling and physically demonstrate how to use them, which required minimal Spanish skills.

Samuel Manhard (?–?) and Regina Manhard, née Abend (?–?), arrived in Montevideo in 1938 with their three-year-old son Erich. Together, they established a women’s ready-to-wear clothing business, selling their own collections designed and sewn by Regina Manhard alongside Uruguayan fashion designers and seamstresses. Their son, Erich Manhard (b. 1935), known as Enrique, opened the first shop of the Chic Parisien group on Montevideo’s main shopping street in 1962. Today, the fashion chain operates 40 stores in Uruguay and, since 2024, one in Argentina; the company is now run by Nathalie Manhard (?), a granddaughter of the founders.

Ready-to-wear women’s fashion was virtually unknown in Uruguay in the 1930s. People either sewed their own clothes or had them tailored. Since many Jewish immigrants came from the textile trade, the arrival of German-speaking Jews led to the development of a ready-to-wear women’s apparel industry in Uruguay. Rudolf Hirschfeld (1906–1998?) from the Hamburg-based fashion store Gebr. Hirschfeld recalled in a 1994 letter that many fashion shops along Montevideo’s main shopping street, 18 de Julio, were owned by German-speaking Jews who owed their success to the establishment of a ready-to-wear sector. As in the case of the Manhard family, garments were made especially for them by small local workshops. Hirschfeld himself worked as a traveling salesman for women’s outerwear, offering his collection to shops in provincial towns. This allowed many women, who could not afford to hire a seamstress, to purchase beautiful and affordable clothing. In this sense, it was a significant form of ‘technology transfer’.

Some refugees also succeeded in integrating into the wider Uruguayan job market. Hans Eisner (1892–1983), a chemist at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin until 1933, arrived in Uruguay with his family via Spain and France and found a job in Montevideo working for the local branch of a Spanish pharmaceutical company. This allowed the family to lead a relatively carefree existence in Uruguay. Peter Heller (1914–1996), who held a doctorate in classical philology and arrived in Uruguay in early 1939 after spending several years in Italy, was eventually appointed professor at the Universidad de Montevideo. Already fluent in a Romance language, Heller had no trouble acquiring Spanish.

There were professional obstacles for lawyers, doctors, and pharmacists, as their academic credentials were not recognized. Some managed to pass the required examinations and obtain professional licenses in Uruguay. Pharmacists were often able to find employment in local pharmacies, since they brought along a new clientèle. Lawyers often focused on contract consultancy and developed second professions on the side. One example is Hermann P. Gebhardt (1903–1984), a German lawyer born in Frankfurt an der Oder, who founded a German-language radio program in Montevideo and later worked as a South America correspondent for West German newspapers.

A particularly important figure was Professor Ludwig Fränkel (1870–1951), formerly director of the university women’s hospital in Breslau (now Wrocław) and full professor at the medical faculty there. He had led the German research group – one of four worldwide – that in 1934 published the correct structure of the corpus luteum hormone. Fired as a result of the ‘Nuremberg Laws,’ Fränkel embarked on a lecture tour through South America. In Brazil, the Uruguayan Minister of Health heard him speak and recruited him as an advisor to the health ministry and as a university lecturer. Fränkel played a major role in establishing a modern endocrinology department at the university hospital, taught at the university, and practiced as a gynecologist. Festschriften (commemorative anthologies) were published in Montevideo in honor of his seventieth and eightieth birthdays.

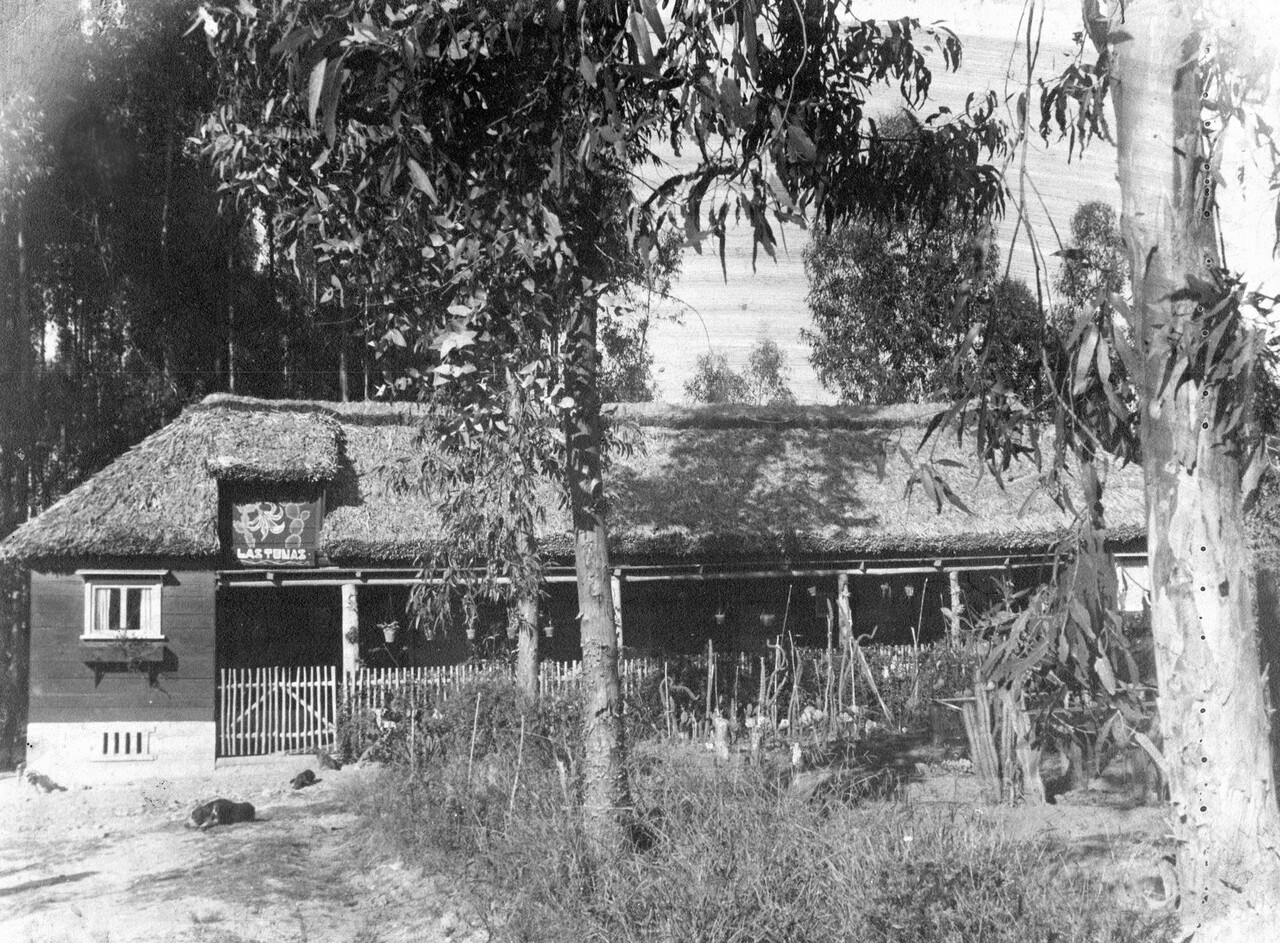

Only a small number of refugees tried to make a living outside Montevideo. Among them was Gerd Aptekmann (1910–2010), who found work on a railway construction project in the interior of the country, and Ursula Eberling (1913–1996), who ran a small nursery with her husband outside Montevideo and sold their wares at the city’s market. The Goldstrom family even moved to Rivera, located in the far northeast of Uruguay near the Brazilian border, about 500 kilometers from Montevideo. Hermann Goldstrom (1900–?) had worked in Germany as a textile buyer for the Alsberg chain and opened a textile store in Rivera with a business partner. Rivera, the capital of the region of the same name, had a population of around 20,000 in the 1930s, with roughly 60,000 residents in the entire administrative district. It was connected to Montevideo via Uruguay’s main railway line.

Fig. 3: House built from shipping containers (‘lifts’) by the Eberling family outside Montevideo; courtesy of Juan Andrés Bernhardt.

These examples represent successful acculturation into the host country, achieved despite great personal sacrifice. But there were also many émigrés who never managed to gain a foothold, and many premature deaths – especially among men – caused by stress, overwork, and illness, in some cases as a consequence of their imprisonment in concentration camps after 9 November 1938. Some of these tragic life stories are documented in the ‘restitution’ files (‘Wiedergutmachungsakten’).

Younger people – especially those who still attended school in Uruguay – generally gained better access to the Spanish language and local culture. Adults with a knack for languages often served as intermediaries between the two worlds. For most émigrés, however, Spanish-language literature and theater remained largely inaccessible. German language and culture thus preserved a small remnant of their former home for many; it was no coincidence that they had taken their beloved German literary classics along into exile. German-language cultural offerings were therefore both important and successful.

The German-language radio hour La Voz del Día – Die Stimme des Tages (The Voice of the Day), which was first broadcast on 23 July 1938, became one of the most important cultural fixtures. To the great disappointment of older listeners, La Voz del Día ceased broadcasting on 29 November 1993. Gebhardt had observed that radio in Uruguay was run on a commercial basis. The station’s broadcasting fees were covered by commercial advertising from shops and businesses founded by the new arrivals. The program was a radio made by émigrés for émigrés and offered guidance on every aspect of daily life. Thanks to the advertisements, listeners found shops and services that spoke their language; they also received news – and, perhaps most importantly, Gebhardt’s daily commentary “Die Welt von heute” (“The World Today”) at the end of each broadcast.

This commentary on world affairs became an important point of reference, and the question “What did Gebhardt say?” a common refrain.

Fig. 4: At the microphone of La Voz del Día, from left to right: Fritz Loewenberg, the station’s deputy director; Hermann P. Gebhardt; and Paul Walter Jacob, artistic director of the Freie Deutsche Bühne (Free German Stage) in Buenos Aires; from the Loewenberg family and given to the author by Rita Loewenberg, Montevideo.

The Voice of the Day was not a one-man show – it gave many refugees a meaningful and responsible role, and for some, even a small income. Moreover, working for the radio was held in high esteem and offered valuable experience amid a daily life often marked by exhausting, underpaid jobs. The radio staff were soon joined by theater people, which naturally led to the idea of putting on entertainment evenings in the form of so-called Rundfunkbrettln – live stage performances associated with the radio program.

Eventually, theater professionals founded their own troupe, which they named Die Komödie. Among its members were Alfred Heller (1889–1949), a theater critic from Vienna and author of several plays that were successfully performed in Europe and even adapted for film; Albert Maurer (1890–1969), who had been artistic director of the Schumann-Theater in Frankfurt am Main; and his wife, the actress Betty Birkens (1889–?). The group’s name said it all: this semi-professional ensemble staged a new premiere each month during the winter season on the stage of a rented hall. Most plays were performed two or three times. In addition to comedies, the repertoire also included serious works such as Liliom by Ferenc Molnár (1878–1952) and The White Disease by Karel Čapek (1890–1938), most of which are little known today. Some younger members of the theater group – such as Fritz (Federico) Wolff (1926–1988) and Heinz (Enrique) Aufrichtig (Okret) (1928–1999) – had arrived in Uruguay as teenagers and later became part of the Uruguayan theater scene. Wolff went on to found his own theater in Montevideo in 1961, the Teatro Universal, where he staged works including those by Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956) and Peter Weiss (1916–1982) in Spanish translation.

Fig. 5: The Die Komödie theater troupe after a performance of Der Raub der Sabinerinnen by Paul and Franz von Schönthan, 1946 (first from left: Federico Wolff; fifth from left: Albert Maurer; second from right: Fritz Loewenberg); from the Loewenberg family and given to the author by Rita Loewenberg, Montevideo.

Performing and partaking in German-language theater in exile provided entertainment, but also allowed members of the German-Jewish educated middle classes to affirm and maintain their identities. This was especially important in an environment that, for all its tolerance and acceptance, largely excluded them from the cultural scene due to the language barrier. This social demotion deepened an underlying tension within the German-speaking Jewish diaspora in Montevideo: on the one hand, its members felt an attachment to German culture; on the other, they had lived through personal exclusion, persecution, and the withdrawal of their citizenship. Was it acceptable for exiled Jews to remain devoted to German culture?

The city’s vibrant musical life offered everyone access to cultural enjoyment. Exiled conductors such as Fritz Busch (1890–1951), Erich Kleiber (1890–1956), and Kurt Pahlen (1907–2003), now largely forgotten, had contracts with the Teatro Colón (Columbus Theater) in Buenos Aires and regularly came to Montevideo for guest performances. Arturo Toscanini (1867–1957), too, had left Italy and conducted in South America. Uruguay basked in this cultural prestige and openly promoted its exiled European musicians in tourism brochures.

In tranquil Uruguay, early émigrés encountered counterparts who had only narrowly escaped deportation. Some had already performed forced labor under the Nazi regime; others had been interned in concentration camps after the November Pogrom. There were certainly no illusions in this exile community about the events unfolding in the German Reich.

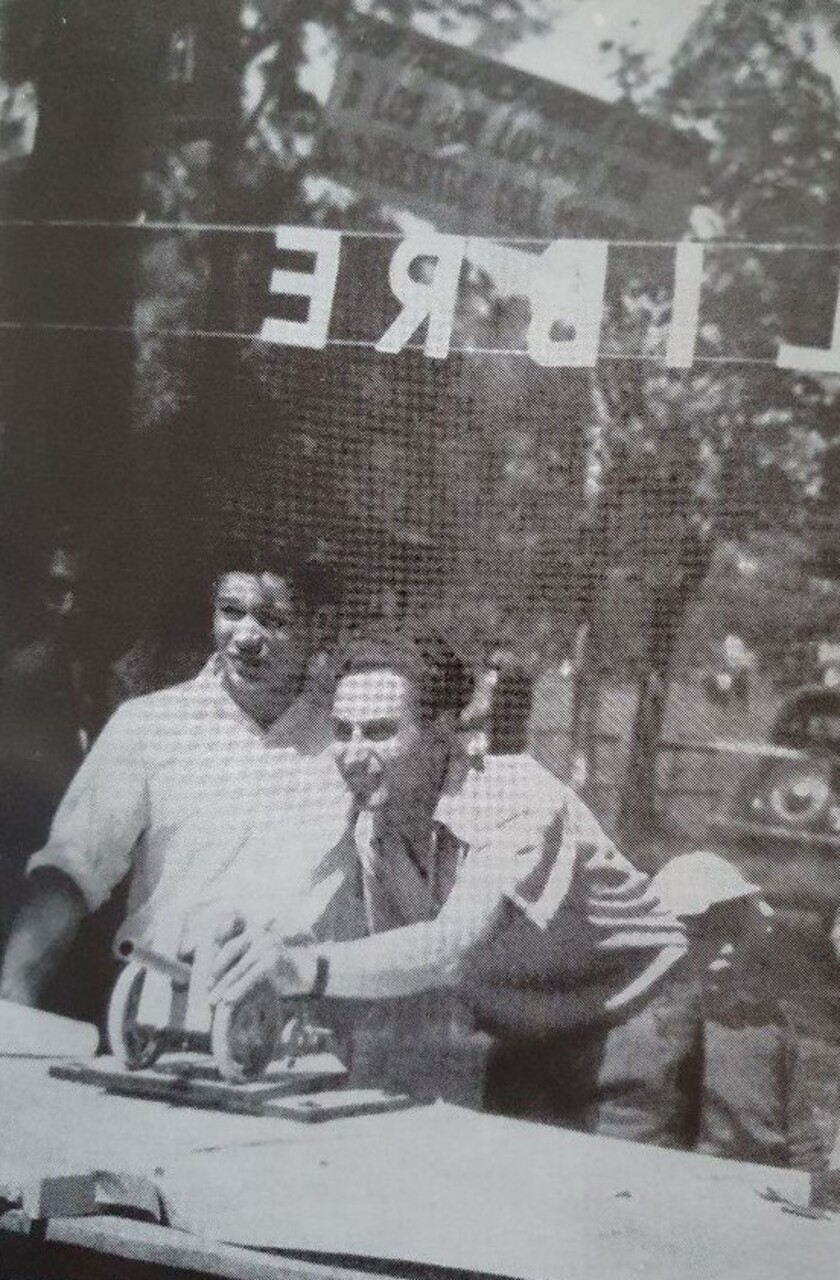

For many German-speaking Jews, support for the Allied cause during the war was taken for granted. While antifascist political activism in exile was possible in Uruguay, the situation was more complicated elsewhere in Latin America. The two most important groups were the Deutsches Antifaschistisches Komitee (German Antifascist Committee, DAK), aligned with the Lateinamerikanisches Komitee der Freien Deutschen (Latin American Committee of Free Germans) in Mexico and communist in orientation, and Das Andere Deutschland (The Other Germany, DAD), which leaned social-democratic. Uruguay imposed only brief restrictions on political activity and the use of the German language. When Uruguay severed diplomatic relations with the German Reich after the Rio de Janeiro Conference of January 1942, La Voz del Día was prohibited from broadcasting in German for about six weeks, and the Gemeindeblatt had to be published in Spanish. At the end of March 1942, all émigrés were once again allowed to engage in political activity freely.

Fig. 6: Willi Israel (left) and Kurt Wittenberg (right) at a solidarity event organized by the DAK, November 7, 1943; Kurt Wittenberg estate, courtesy of Andreas Wittenberg.

After the Second World War, some refugees left Uruguay for Argentina, Brazil, or the United States. Others returned to Germany, including the newly founded German Democratic Republic (East Germany). In the early 1960s, there was a wave of emigration to Israel. Most, however, stayed in Uruguay. The families of those who had succeeded in establishing themselves professionally remain part of Uruguay’s middle class to this day.

One of the lasting legacies of German-speaking Jewish immigration is the NCI, which today serves as Montevideo’s Reform Jewish congregation in the spirit of Breslau and Berlin. However, the German language has all but vanished. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the Jewish refugees generally no longer speak the language, and their spouses come from all the Jewish Communities. While there is still interest in their families’ country of origin, they have successfully acculturated into Uruguayan society.

Deutsche Schule Montevideo (German School of Montevideo): DSM - Colegio y Liceo Alemán

Bernd Müller, Deutsche Schule Montevideo 1857–1988, Müller: Montevideo, 1992.

Nueva Congregación Israelita (New Hebrew Congregation, NCI), Montevideo: https://www.nci.org.uy/

Sonja Wegner, “Das Theater und die Emigranten: Montevideo, die Komödie und das Teatro Universal“, in: Münchner Beiträge zur jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur, 10(2), 2016, 46–57. Anzeige von Das Theater und die Emigranten: Montevideo, Die Komödie und das Teatro Universal | Münchner Beiträge zur jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Sonja Wegner studied history and German language, and literature at the University of Essen. Since 1993, she has undertaken several research stays in Uruguay. She worked as a study tour guide in Spain, Portugal, and England for many years. Doctorate under Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Benz at the Center for Research on Antisemitism at the Technical University of Berlin on “Exile in Uruguay 1933–1945”. Several publications on emigration in South America, including Zuflucht in einem fremden Land. Exil in Uruguay 1933–1945 (Berlin 2013). Sonja Wegner lives and works as a freelance historian and journalist near Cologne.

Sonja Wegner, Uruguay: A New Home in South America? (translated by Jake Schneider), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-11> [February 21, 2026].