Born on August 18, 1914 in Berlin,

Germany

Died on October 31, 1986 in Cape Town, South

Africa

Occupation: Photographer

Migration: Mandatory Palestine, 1933 | Great Britain, ca. 1936 |

South Africa, 1937

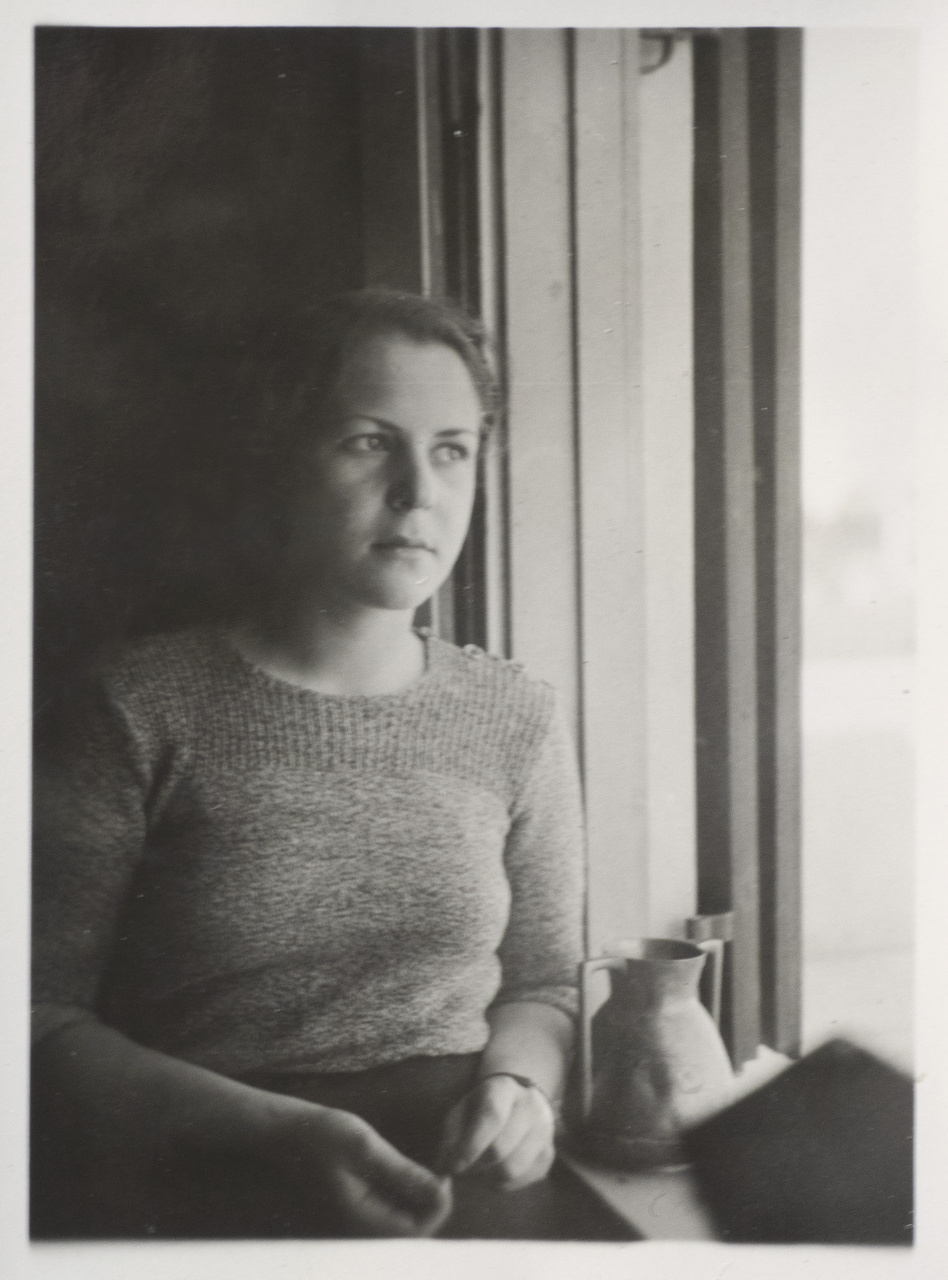

Fig. 1: Unidentified photographer, Anne Fischer in exile, ca. 1935–1936; private collection, Cape Town, South Africa.

“As you know, we are living in worried times. I have often thought of living somewhere else, but where?” Anne Fischer, letter to Aart and Valerie Bijl, 12 December 1977, private collection. Writing in South Africa during the height of apartheid, this was not the first time the German-Jewish photographer Anne Fischer had found herself asking this question. Politicized by the rise of fascism in Europe and forced into exile by the Nazi regime, Fischer was uniquely poised to document fundamental changes in South Africa in the years leading up to and during National Party rule. When she first arrived in Cape Town in 1937, Fischer refused to assimilate into South Africa’s then-shifting definitions of whiteness. A secular Jew, she found commonalities with other exiles in the country based on their shared experiences of persecution, belief in racial equality, and desire for social justice.

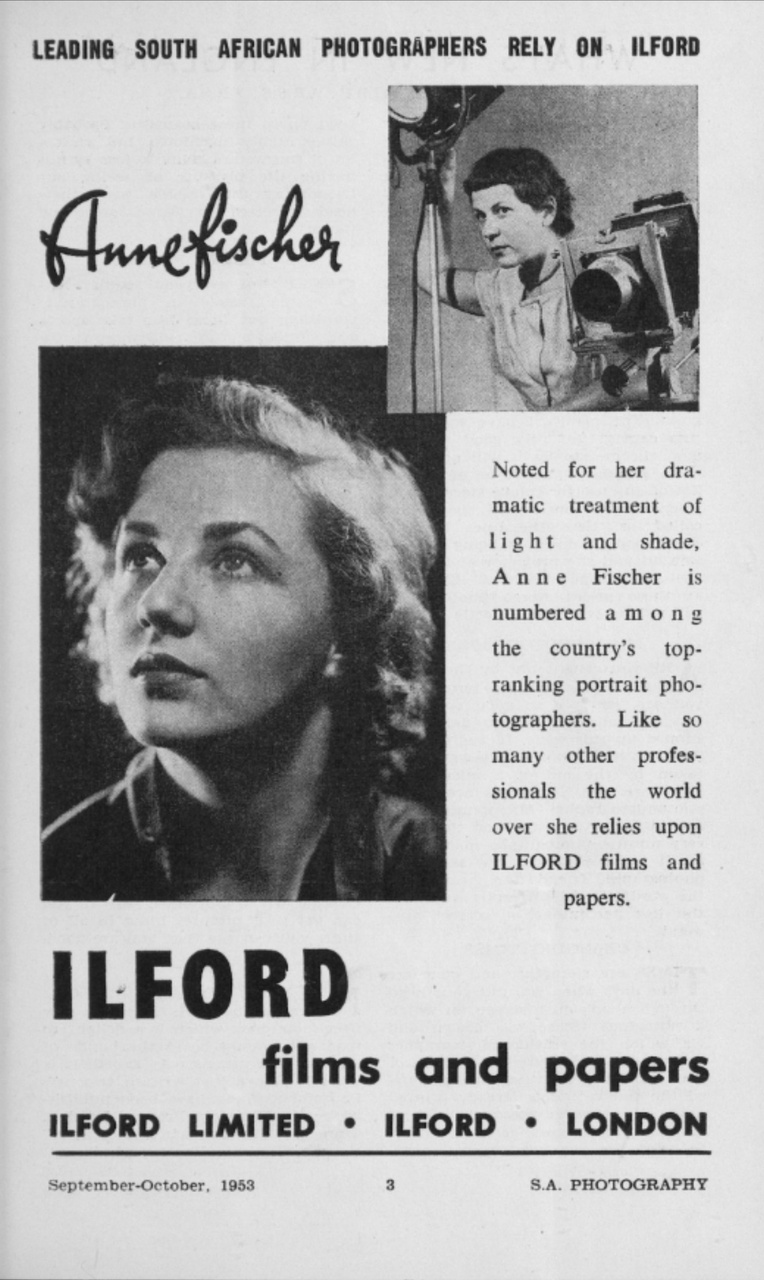

As a young exilic photographer, Fischer captured radical social transformations in her new colonial context and contributed to South Africa’s early antiracist resistance movements with her lens. Although she later became one of South Africa’s most acclaimed portraitists, today little is remembered about her life or the extensive documentary work she produced.

Annemarie Eva Fischer was born into a middle-class Jewish family in Berlin on 18 August 1914. While she left behind no written accounts of her childhood in Germany, her personal photo albums from this period relate a seemingly calm life punctuated by family trips to Switzerland and quiet afternoons in Berlin’s gardens. As she grew older, Fischer embraced the socially and politically liberal policies of the Weimar Republic and turned to photography for the artistic and economic potentials she knew the medium could afford a young woman of her class. Shortly after she turned sixteen, she enrolled in a three-year photographic course which was cut short by the rise of Nazism and the subsequent emigration of her mentor. When her father died, leaving her orphaned, Fischer decided to heed her teacher’s advice and began making plans to leave Germany. In March 1933, she applied for a new passport, and in October of that same year, left Berlin for Tel Aviv with little more than a small inheritance and her camera Rolleiflex.

Fig. 2: Unidentified photographer, page from Anne Fischer’s personal album with images of her as a child in Germany, ca. 1923; private collection, Cape Town, South Africa.

Despite her inability to speak Arabic or Hebrew, Fischer managed to secure several small photography commissions in Tel Aviv and began working to build a new life for herself in Palestine. She was part of the Fifth Aliyah, the wave of immigration between 1929 and 1939, which included a large share of Jews from Germany. While we have limited written information about the time Fischer spent in the country under British rule, the personal photo albums she created during this period help to visually chronicle her first few years in exile. Unfortunately, Fischer refrained from identifying most of the individuals in her albums and left very few details about the type of commercial work she undertook to earn a living. Whether or not she affiliated with any political groups, established connections with local artists, or met any of the other Weimar women photographers who had similarly sought refuge in the same city – such as Ellen Auerbach (1906–2004) – remains unknown.

Fig. 3: Unidentified photographer, Anne Fischer in Mandatory Palestine, ca. 1933–1936; private collection, Cape Town, South Africa.

After three years of struggling to find work as a photographer in Palestine, Fischer traveled to Greece, backpacked up through the former Yugoslavia into France, and eventually arrived in England, where she was denied asylum and again forced to emigrate. With the help of a Jewish refugee group in London, she secured passage on a ship bound for South Africa – a country she knew nothing about but in which she had been told she could find refuge.

Fischer set foot on Cape Town’s docks in early March 1937, just as South Africa was tightening its restrictions against German-Jewish refugees. Between 1933 and 1939 around 6,000 Jews from Nazi Germany found refuge in South Africa with Cape Town being the main port of arrival. Almost immediately after she arrived in the city, Fischer secured a flat, built a makeshift darkroom, and threw herself into the social spheres of the city’s politically fractured Left. Her bohemian character and progressive leaning drew her to Cape Town’s liberal circles, where she became acquainted with the city’s leftist intellectuals, avant-garde artists, and active trade unionists. Among those she met was Bernhard Herzberg (1909–2007), a trade unionist and German-Jewish refugee from Hanover, whose politics and pragmatism seemed to match, if not rival, her own.

By the end of Fischer’s first year in South Africa, she and Herzberg were living together, and her political life had become intimately intertwined with his. When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, Herzberg was naturalized as a British citizen, and he and Fischer married, in part to protect her from the possible threat of internment as an ‘enemy alien.’

Fischer’s relationship with Herzberg in these early years helped to broaden her exposure to Cape Town’s various leftist circles. Shortly after his arrival in South Africa in 1933, he had been introduced to Dr. Abdul Hamid (1887–1973) and Zainunnisa ‘Cissie’ Gool (1897–1963), two leading political activists, and had begun attending meetings in their home. When the civil rights leader Goolam Gool (1905–1962) launched the New Era Fellowship in 1937, Herzberg (and it is presumed Fischer) began frequenting the study groups and lectures the organization held. In 1938–1939, Fischer joined the National Liberation League, an antiracist coalition co-founded by Cissie Gool, and began undertaking work alongside its members in Langa, one of South Africa’s first racially segregated locations. In addition to producing pictures that disclosed the dire living conditions and exploitation of Langa’s residents, Fischer also documented the affirmative lived experiences of those she and Herzberg personally knew. Although ultimately never published, these images signal the beginning of Fischer’s commitment to a documentary mode that urged an unsentimental confrontation with the everyday, one that she would continue to formulate (and variously articulate) throughout the 1940s in close collaboration with members of Cape Town’s antiracist Left.

Fig. 4: Anne Fischer, Bernhard Herzberg and Anne Fischer, Cape Town, ca. 1937–1941; private collection, Cape Town, South Africa.

In 1940, Fischer had an affair with Max Gordon (1910–1977), a prominent trade unionist and member of the Workers Party of South Africa. Herzberg promptly filed for divorce. Following their separation, the young photographer broadened her focus and began to traverse the country with her camera. While the photographs she made between 1941–1945 aesthetically countered the pictorialist imagery she found dominated South Africa’s more conservative photography salons during this period, Fischer’s work was often misunderstood by local audiences unfamiliar with the ideological differences between right and left-winged versions of the modernist Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) – a style of realistic and critical art that emerged in Germany during the 1920s. The unexpected reception of her work in South Africa forced the young photographer to reckon with her medium’s paradoxes in a context where avant-garde aesthetics and progressive politics were not always synonymous.

Fischer’s frustration with her inability to control the meaning of her work amid the rising tide of Afrikaner nationalism after the Second World War ultimately led to her interest in pairing her images with politically brazen texts. In 1946–1947, she worked with the Marxist literary critic Dora Taylor (1899–1976) on a photobook that put forth a scathing critique of the National Party and its racist policies. Tentatively titled Vale of Grace, their project was completed in the months leading up to South Africa’s pivotal 1948 elections, but was never published.

Despite the Left’s attempts to counter the rise of Afrikaner nationalism in South Africa through protests, lectures, and the production of propaganda, racist ideologies became further entrenched in the country as the 1940s progressed. Fearing the outcome of the coming elections and recalling her earlier experiences in Berlin, Fischer decided to leave Cape Town for London in early 1948. In England, a nation that had once denied her refuge, she held an exhibition of her South African work, joined the British Institute of Photography, and opened two photography studios.

When she arrived in London, Fischer found a new community for herself among the city’s left-leaning émigrés and avant-garde artists. North-west London had seen a large influx of German-speaking refugees in previous years. After the United States and Mandatory Palestine, the UK took in the largest number of Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in Central Europe. Among the individuals Fischer met and befriended during this period were the South African architect Theo Crosby (1925–1994), the German-Jewish artist Hans Unger (1915–1974), and her second husband, the Dutch-born South African designer Pieter Bijl (1912–1970). Alongside the commercial work Fischer produced to earn a living, she also took hundreds of documentary photographs on the streets of London, this time in a state of double exile.

Fig. 5: Pieter Bijl, Anne Fischer with her Rolleiflex, London, ca. 1948–1950; private collection, Cape Town, South Africa.

In August 1950, faced with financial precarity and an uncertain future in England, Fischer and Bijl decided to return together to South Africa. Almost immediately after they arrived in Cape Town, Fischer rented a commercial studio space and began working to establish a new life for herself under National Party rule. That year, she became the main photographer for Cape Town’s Little Theatre and began to work closely with its then-director, Leonard Schach (1918–1996). Before censorship laws and segregationist legislation in the mid-1960s forced work of this sort underground, Fischer documented plays that were produced by the Bantu Theatre Company of Cape Town and other theatrical productions that were put on by several of the city’s other non-racialist groups.

Comprising images of plays that were written and produced by banned playwrights, as well as photographs of more innocuous productions that were performed more simply for the sake of the stage, Fischer’s commercial work emblematizes some of the key contradictions that would come to mark her career as a professional photographer during apartheid. As was the case for many politically committed South African artists, Fischer relied on the income she was able to generate from commissions to fund the more politically and socially conscious documentary work she wanted to produce – work that, because of its nature, often went unremunerated.

Over the course of the next three and a half decades, Fischer earned a reputation for herself as one of Cape Town’s most sought-after theatre, portrait, and wedding photographers. Her post-1948 peer group comprised outspoken dissident novelists and poets, as well as leftist artists and political activists. Despite having cultivated a large social circle in her adopted country, however, the now well-established photographer felt incredibly isolated within it. In letters she sent to her stepson during the height of apartheid, for example, Fischer wrote that she struggled with the “insincerity of [the] people” she met at the exhibition openings she was expected to attend and expressed her frustration with many of her assimilationist Jewish clients’ racist attitudes. “I don’t go along with it,” she told him, “so I don’t go anymore. […] I am afraid my sort of people are [sic] not easy to find.” Anne Fischer, letters to Aart and Valerie Bijl, 3 April 1975 and 23 October 1974, private collection.

Fig. 5: “Anne Fischer: Leading South African Photographers Rely on Ilford,” Ilford Advertisement, South African Photography Journal, September–October 1953; courtesy South African National Library.

As she had done during earlier tumultuous periods in her life, Fischer attempted to cope with her anxieties by throwing herself into work. In addition to running her commercial photography studio, she also began making plans to exhibit some of the earlier documentary work she had produced in South Africa. After months of planning, she held two retrospective shows in Cape Town between 1975 and 1977. In 1984, Fischer opened her last exhibition in Johannesburg. Two years later, in 1986, she passed away from chronic lung disease.

Despite attempts by now well-known South African photographers – such as David Goldblatt (1930–2018) and George Hallett (1942–2020) – to recuperate Fischer’s documentary work for posterity, this portion of her archive was again subsumed by history after her death. While art historians have begun to trace the paths of Weimar women photographers in exile, their work, with few exceptions, has primarily focused on practitioners who were able to escape Nazi Germany for European and North American centers. The fact that Fischer’s archive was mainly produced in and remains on the African continent – a place that is still largely considered peripheral in studies on modernism – has only contributed to her continued exclusion from the field of art history.

Fischer’s experiences of racial persecution and exile motivated her to work differently than her similarly trained white South African contemporaries. While her youth and leftist politics shaped how she was seen in her new colonial context, her gendered experiences of exile and antiracist attitudes also informed how she engaged with and depicted others. Recuperating details about her life and work not only helps to expand our understanding of the contributions German-Jewish women made to photography but sheds light on some of the twentieth century’s most powerful (though as yet unexplored) histories of transnational resistance and resilience.

Anne Fischer Photographic Archive, Ibali Digital Collections, University of Cape Town Libraries’ Special Collections, https://ibali.uct.ac.za/s/uct-photography/item-set/108032.

Anne Fischer Collection, Social History Center, Iziko Museums of South Africa, Cape Town, https://www.iziko.org.za/museums/social-history-centre/.

Okwui Enwezor/Rory Bester (ed.), Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, New York: International Center of Photography, 2013.

Pam Warne, “Anne Fischer,” in: Encyclopedia of South African Theatre, Film, Media, and Performance, https://esat.sun.ac.za/index.php/Anne_Fischer.

Pam Warne, “The Early Years: Notes on South African Photographers Before the Eighties,” in: Robin Comle/George Hallet/Neo Ntsoma (ed.), Women by Women: 50 Years of Women’s Photography in South Africa, Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2006, 15–25.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Jessica Williams Stark’s research focuses on modern African art and the global histories of photography. She earned her PhD in History of Art and Architecture from Harvard University and was most recently the McCormick Postdoctoral Research Associate in the History of Photography and Lecturer in the Department of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University. Stark’s research has been generously supported by the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, the Fulbright Program, the Peter E. Palmquist Foundation Fund for Historical Photographic Research, and the Foreign Language and Area Studies Program. Her work can be found in October, Women and Photography in Africa: Creative Practices and Feminist Challenges, Urban Exile: Theories, Methods, Research Practices, and Safundi, and is forthcoming in a special issue of History of Photography dedicated to studies on exile and migration. Stark serves on the board of the Photography Network, an organization that fosters discussion, research, and new approaches to the study and practice of photography, and is currently the Research Fellow at the Vision & Justice Initiative.

Jessica Williams Stark, Anne Fischer (1914–1986), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-20> [February 24, 2026].