After the Shoah, Australia became a center of diasporic Jewish life along with the United States. Yet the Australian continent, within Oceania, has had a growing Jewish community since the nineteenth century. While the large wave of emigration from the 1820s onwards led most German Jews westward, to the United States, some turned in the opposite direction and chose to emigrate to Australia. The first Jewish immigrants arrived on prison ships, with other convicts, to what was then a British penal colony beginning in 1788. Although the vast majority of the convicts were of British origin, ship manifests also list a few Jewish prisoners from German-speaking regions. The first ’free settlers’ came to Australia voluntarily, beginning in the 1820s. Finally, the Gold Rush of the mid-nineteenth century attracted gold prospectors and businesspeople to the distant continent – including Jews, who took part in establishing Australia’s first organized Jewish communities.

In the twentieth century, these religious institutions would play an important role as places of refuge. Despite the Australian government’s severe restrictions on immigration after 1933, Australia became an important sanctuary for Jewish refugees from Europe. Among them were around 3,500 Jews from German-speaking Europe. By the end of the war in 1945, approximately 20,000 Shoah survivors had found a new home in Australia. They left a mark on the country’s diverse Jewish life and its collective memory that remains visible to this day. With more than fifty Jewish community centers, around seventy synagogues, and three major Jewish museums, Australia ranks as a major center of the Jewish diaspora.

From the seventeenth century onwards, Portuguese and Dutch seafarers undertook several exploratory voyages along the coasts of what was initially called ‘New Holland.’ However, it was the Englishman James Cook (1728–1779) who was credited in Western history books for officially ‘discovering’ the continent. In the US War of Independence, the British Empire under George III (1738–1820) forfeited thirteen of its North American colonies – including most of the Empire’s penal colonies. Now, the supposedly uninhabited Australian continent posed an attractive alternative.

The practice of shipping convicts to remote British colonies persisted until 1868. These transported prisoners included hundreds of Jewish men and women from the British Empire, but also some from the predominantly German-speaking states of Prussia, Hesse, Baden, and Bavaria. Many had run afoul of the law during longer or shorter stays in the United Kingdom and were subsequently deported as prisoners of the British Crown to the first colony, New South Wales. However, the remote continent was anything but uninhabited. Indeed, Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders had lived there for over 50,000 years. Yet their existence was ignored. Even after the unification of the individual British colonies into the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, the Indigenous population was not granted civil rights. The so-called ‘White Australia Policy’ was primarily aimed at preventing Asian immigration, but in practice, it affected all ‘non-Europeans,’ including Jews from Eastern Europe who were not naturalized British citizens. Australia’s Indigenous population is victimized by systemic discrimination, exclusion, and racism to this day.

The first census conducted in 1828 recorded 150 Jews in the colonial settlements along the Australian coast. There is documentation of at least thirteen Jews from German-speaking territories during this period. Between 1810 and 1820, the settlement of Port Jackson evolved into the city of Sydney, where the first synagogue was opened in 1844. In Hobart, a city on the island of Van Diemen’s Land (now known as Lutruwita or Tasmania), the 260-member Jewish community succeeded in establishing a synagogue in 1843. Special pews were set up for prisoners, which are still preserved today. The Hobart Synagogue remains the oldest continuously used synagogue building in Australia. From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, German Jews also settled in Hobart. Among them was the Prussian-born Jacob Frankel (1812–1899), one of the founding members of the Hobart Hebrew Congregation. Another notable figure was Leo Susman (1832–1903) from Altona, who established a modern department store in Hobart, offering goods imported from Europe.

Fig. 1: The Hobart Synagogue, built in the Neo-Egyptian style, around 1900. The inscription above the entrance cites Exodus 20:24 "בכל המקום אשר אזכיר את שמי אבוא אליך וברכתיך" (“In every place where I cause My name to be mentioned I will come unto thee and bless thee”); Pretyman Family Estate, Libraries Tasmania’s Online collection: https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/NS3121-1-7/NS3121-1-7-1.

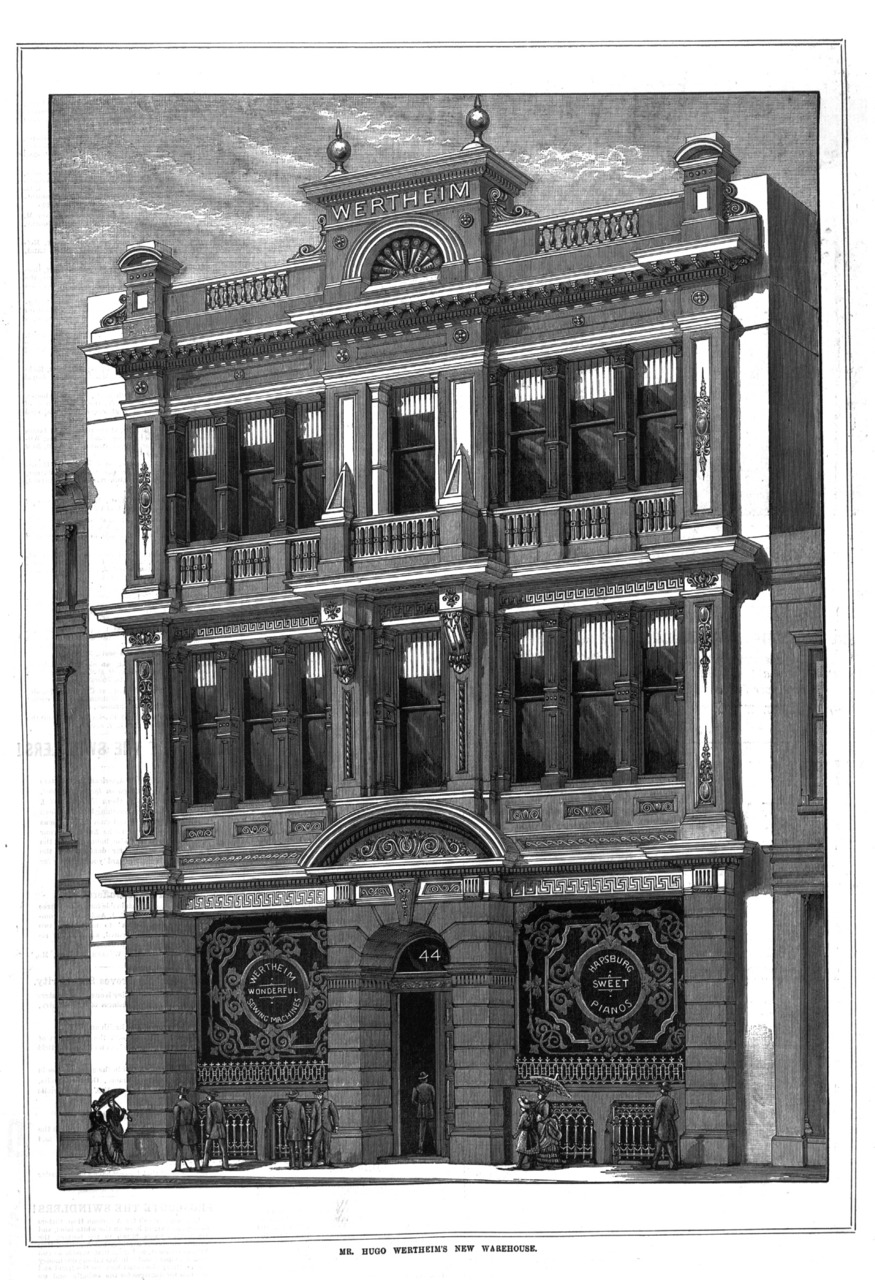

In southeastern Australia, a larger settlement gradually emerged around 1835, eventually developing into the city of Melbourne. The first Jewish religious services were held there in 1839, and by 1841, the Jewish Congregational Society had been established. By 1865, Melbourne had surpassed Sydney in population, and the discovery of gold made the city one of the wealthiest in the world by the 1880s. People from all over the globe were drawn to ‘marvellous Melbourne,’ where economic opportunities extended far beyond the goldfields. Some German Jews, who had been subject to numerous forms of legal discrimination in their birthplaces, saw Australia’s colonies as a chance to establish themselves in business. The Jewish population of Victoria numbered only around 350 in 1851, but within a decade, it had grown to nearly 3,000. In 1870, a second synagogue, the St. Kilda Hebrew Congregation, was established in Albert Street. This new synagogue was founded by the businessman Moritz Michaelis (1820–1902), originally from the town of Lügde, near Hanover, who also served as the acting consul for Prussia. Melbourne became a major center of commerce, and the vast majority of Jews who settled there came from German-speaking regions of Europe. One such individual was Hugo Wertheim (1854–1919) from Lispenhausen, Hesse, who arrived in Melbourne in 1875 and built a thriving business importing sewing machines, bicycles, pianos, and other mechanical devices from Europe to Australia. The Gotthelf family from Burgdorf near Hanover also established a successful trading company in Sydney called Feldheim, Gotthelf & Co., which later grew into a trend-setting Australian department store.

Fig. 2: The three-storey Wertheim Department Store on Lonsdale Street in Melbourne, 1886; Public Domain, State Library Victoria: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/252215.

Jewish communities also emerged in rural areas. The towns of Ballarat and Bendigo, located inland northwest of Melbourne, became important centers of gold prospecting and attracted numerous Jews from the German-speaking world. Ballarat’s first synagogue was consecrated in 1855; the town’s second synagogue, built only six years later, still stands today. Emanuel Steinfeld (1828–1893), born in Oberglogau (Głogówek), Prussia, established a furniture business in 1856 and became a prominent businessperson and socialite in Ballarat. Other Jewish merchants, primarily from the Posen region (which had been part of Prussia since 1815), settled in the town. Later, Steinfeld even served as Ballarat’s mayor and went on to become a member of Victoria’s state parliament in 1892. Beyond economic prospects, it was also these sorts of political opportunities that made living in Australia attractive, rights and privileges that would be out of reach to Jews – and especially Jewish women – in German-speaking parts of Europe for many years to come.

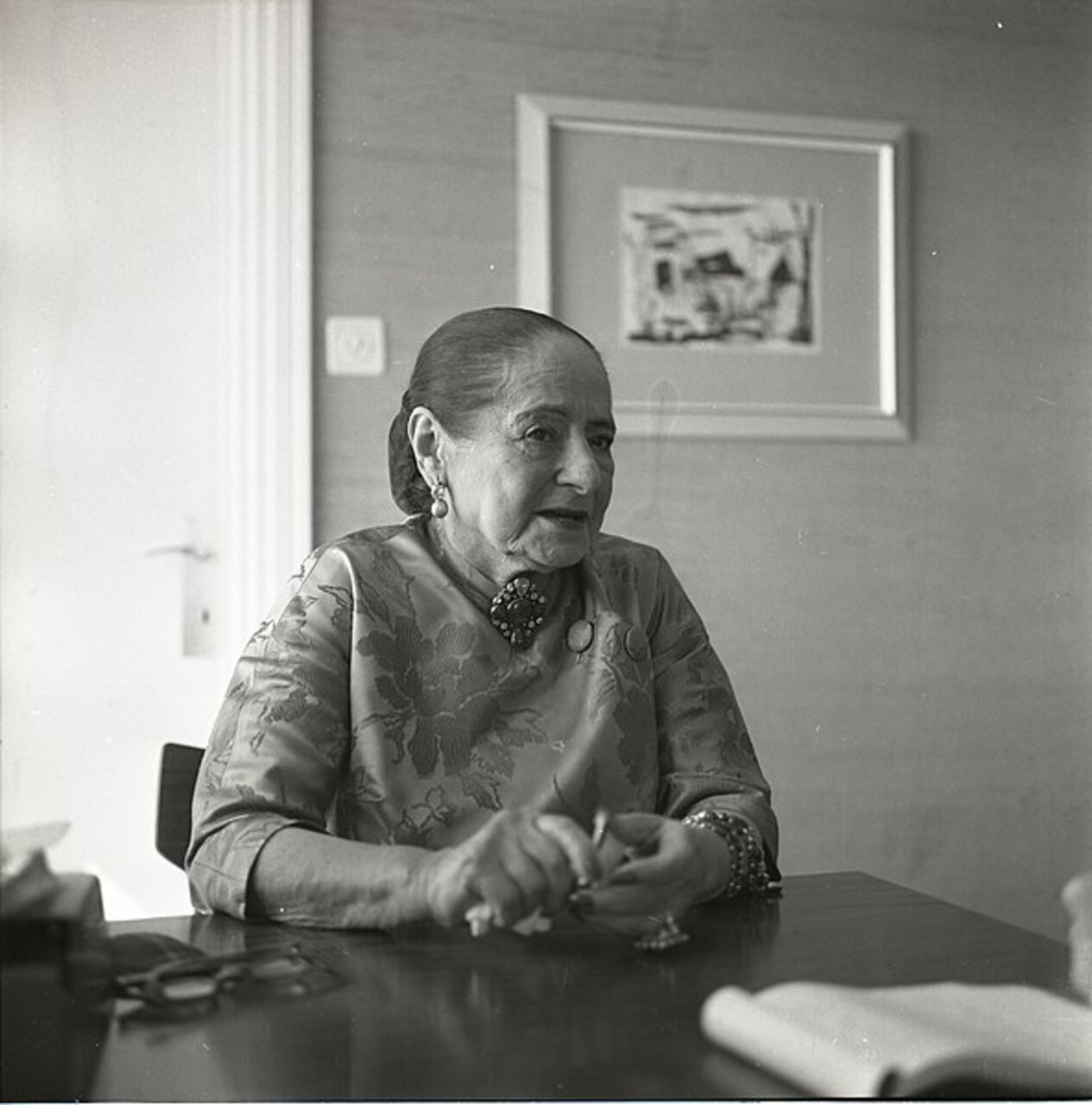

An outstanding example of the economic success of a Jewish immigrant is Helena Rubinstein (1870/72–1965) from Kraków, which was then part of the Habsburg Monarchy. Raised in a Yiddish- and Polish-speaking environment, Rubinstein later lived in Vienna and Switzerland, where she began studying medicine but did not complete a degree. When her father tried to arrange her marriage to a much older widower, Rubinstein had different plans for her future. She decided to follow her mother’s brother to Australia. He ran a business in the small town of Coleraine, about 350 kilometers west of Melbourne. In 1896, Rubinstein arrived in Australia aboard the Prinzregent Luitpold, initially working for her uncle’s family as a nanny, but soon began producing and selling skincare creams. In 1902, Rubinstein opened her first beauty salon in Melbourne, which marked the beginning of an international career. Rubinstein expanded her business not only within Australia but also to New Zealand, France, Great Britain, and the United States. Her company became synonymous with cosmetics and beauty products, and to this day, the Helena Rubinstein brand remains a symbol of entrepreneurial success.

Fig. 3: Helena Rubinstein – successful entrepreneur, art collector, and philanthropist, 1962; Boris Carmi, Meitar Collection, National Library of Israel/The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection, ARC. 4* 2069/19440.

Fig. 4: Advertisement for Helena Rubinstein beauty products in The Home: An Australian Quarterly, 1940; The Home. An Australian Quarterly; Vol. 21 No. 3 (1 March 1940).

The distance from Britain and the lack of infrastructure posed serious challenges for Jewish religious observance. When Rabbi Jacob Saphir (1822–1886), an emissary from Jerusalem, visited Australia in the 1860s, he observed that Jews were not keeping strictly kosher diets and that many Jewish business owners did not close their shops on Shabbat. Thus, when the aforementioned Gotthelf family from Burgdorf began producing the first kosher matzah in Australia, it was greeted with great fanfare.

For a long time, there was a shortage of ritual objects and religious literature. Since considerably more Jewish men had immigrated, many of them married non-Jewish women. Various newspaper articles attest that Jews back in Europe were interested in the welfare of their relatives and friends in these colonial outposts. For example, the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums, one of the most important publications of the Jewish community in Germany, reported in 1857:

“According to a letter to the Jewish Chronicle from Melbourne, Australia, there is a great desire in Australia for Jewish girls to immigrate, as there are several thousand young men of our faith who could feed a family but are prevented from marrying by a shortage of Jewish women.” Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums, 21 (1857), no. 38, 521.

Such reports, which reflect the international (two-way) links within the German-Jewish diaspora, were designed to alleviate this demographic imbalance. While the gender disparity evened out somewhat during the Gold Rush, mixed marriages remained common into the twentieth century. In 1921, thirty percent of married Jewish men and sixteen percent of married Jewish women had non-Jewish spouses. Chain migration also shaped the development of the Jewish community in Australia, influencing marriage patterns and transnational connections. It was common for Jewish migrants to travel back to their European countries of origin, either to find a spouse or to convince other relatives to emigrate – and in either case return to Australia as a family. The strong transnational links to Europe were also evident in religious affiliations and identity. Jewish communities in Australia remained under the authority of the Chief Rabbi of Britain, the seat of the Empire. The appointment of Nathan Marcus Adler (1803–1890), born in Hanover, as Chief Rabbi of London in 1845 reinforced the sway of the German rabbinate, which was reflected in religious education, liturgy, and the appointments of rabbis across Australia.

Unlike in many other places where German-Jewish immigrants settled, Reform Judaism did not establish itself in Australia until the 1930s. This was largely due to the efforts of Rabbi Elias Blaubaum (1847–1904), who grew up in Rotenburg an der Fulda. The Chief Rabbi of Britain, Hermann Adler (1839–1911), son of Nathan Marcus Adler, considered Blaubaum moderate enough to tolerate the relatively lax religious practices in Australia, yet conservative enough to keep Melbourne’s Jewish community from becoming even more progressive. Although Dattner Jacobson, a rabbi from Vienna, founded the Temple of Israel in 1870 – the first Reform congregation in Australia – the movement did not catch on. When Jacobson left Melbourne after only five years and emigrated to the United States, the Reform congregation dissolved. Reform Judaism would only gain greater significance in Australia with the arrival of Jewish refugees from Europe in the 1930s. Blaubaum, who enjoyed considerable support in Melbourne, represented Modern Orthodoxy (known as Neo-Orthodoxie in German), a religious movement founded in the second half of the nineteenth century by the Hamburg-born Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808–1888). It was Blaubaum who introduced this German-Jewish denomination to the country; it went on to become very influential in the religious life of Melbourne.

The outbreak of the First World War had a lasting impact on Australian society and politics. As a dominion of the British Empire, the self-administered colony entered the war in 1914, sending approximately 400,000 volunteer soldiers – nearly ten percent of the male population. The war resulted in heavy losses and deeply shaped Australia’s national consciousness, particularly through the Battle of Gallipoli in present-day Turkey: often remembered as the defining moment in the formation of an ‘Australian nation.’

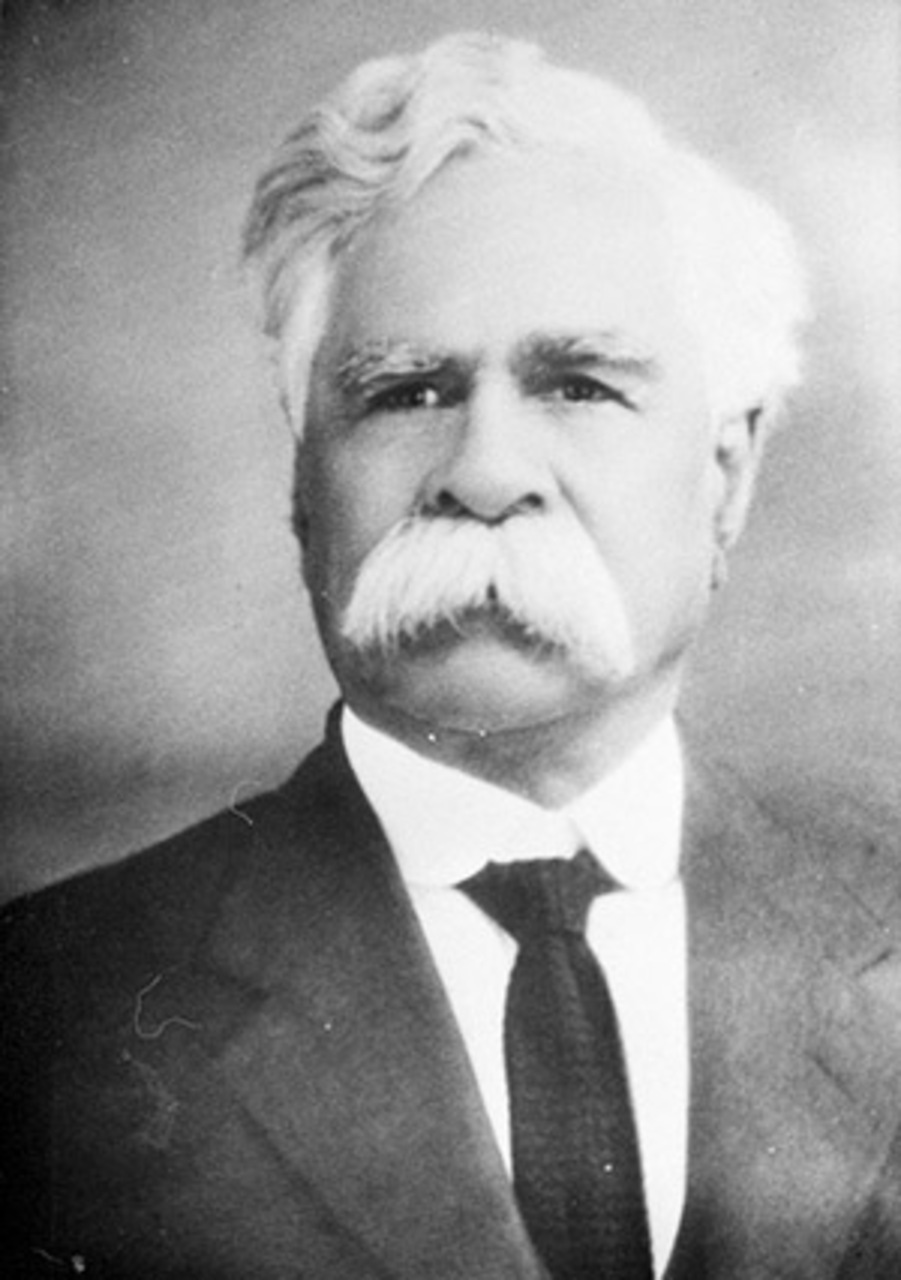

A key figure in this context was John Monash (1865–1931), the son of a Jewish couple who had emigrated from Prussia. His uncle was the renowned Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz (1817–1891). Monash worked as an engineer and gained recognition for his leadership as a commander in Egypt and during the Gallipoli Campaign. He eventually rose to the rank of general, and remains one of the best-known military figures in Australian history. This was a remarkable achievement indeed, given that Jews in Europe had long been excluded from high military ranks, even after their legal emancipation. In the German military and society following the First World War, antisemitic conspiracy theories were widespread, notably the ‘backstabbing’ myth blaming Jews for Germany’s defeat. By contrast, Monash, the first Jewish general in Australia, was widely honored. Today, Monash University in Melbourne bears his name, and his likeness appears on Australia’s 100-dollar bill.

Fig. 5: Sir John Monash outside the generals’ headquarters near Villers-Bretonneux, France, May 1918; Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, P3/54.

Despite this recognition, antisemitism remained prevalent in Australia, both within and outside the military. Monash himself faced opponents who attempted to discredit him as a German spy. However, due to his high standing, he successfully fended off these efforts to smear his reputation. Moreover, he spoke out on behalf of other Germans in Australia who faced similar accusations. Even as an unknown number of soldiers from German-Jewish families fought as Australians in the First World War, numerous civilians from the German Empire were classified as “enemy aliens” and interned.

One such individual was Dr. Eugen Hirschfeld (1866–1946) from Lower Silesia (now southwestern Poland), who had emigrated to Australia in 1890. He settled in Brisbane, where he became a leading physician specializing in tuberculosis and dengue fever research at the local hospital. Hirschfeld was deeply dedicated to the Brisbane community. He founded a society to promote the German language and culture, was appointed Imperial German Consul in 1906, and was a founding senator of Queensland University. Despite having already been naturalized, Hirschfeld was interned as an ‘enemy alien’ during the war. His wife, Annie Hirschfeld (1872–1944), and their three sons retained their freedom. In 1919, he was deported to Europe, eventually relocating to the United States, where he worked as a physician. After a prolonged struggle with the authorities, Hirschfeld was allowed to return to Australia in 1927 – largely thanks to an intervention by Monash, who had tried to prevent his deportation in the first place. Many Jews from German-speaking regions suffered similar fates, including the Munich-born physicist Peter Pringsheim (1881–1963), who had traveled to Australia to attend a scientific convention, only to be detained at Holsworthy Internment Camp.

Yet Jews of German origin had already considerably shaped Australia’s cultural, economic, and social life since the nineteenth century. In cities like Melbourne and Sydney, they had established Jewish communities, educational institutions, and cultural organizations that had a major impact on the country’s intellectual and social landscape. Among them was Rabbi Elias Blaubaum, who in 1879 co-founded the Jewish Herald newspaper in Melbourne, which he edited until his death in 1904. The publication had a wide readership and served as a central forum for the Jewish community. Similarly, Alfred Harris (1870–1944), whose father came from Prussia, played a key role in Australian media. As a publisher, he established several newspapers, including the Hebrew Standard of Australasia, all of which fostered public discourse both within and beyond the Jewish community.

The German-speaking Jewish immigrants who integrated fairly rapidly into Australia’s broader Jewish community stood in sharp contrast to the German-speaking Lutherans who also immigrated from the nineteenth century onwards. German Lutherans tended to settle in self-contained communities – such as the Barossa Valley in South Australia – where they developed a distinct dialect known as Barossa German. By contrast, German Jews acculturated much more quickly into Anglo-Australian society. Although certain neighborhoods, such as St Kilda and South Yarra in Melbourne, had a larger concentration of Jews, they were anything but insular. German- and English-speaking Jews lived side by side and were engaged with mainstream non-Jewish society.

In 1933, Australia’s Jewish population numbered approximately 23,000. By the end of 1937, as Nazi persecution in Europe escalated, around 150,000 Jews had fled from Germany. Only a small fraction of them reached Australia. A major reason for this was the country’s restrictive immigration rules and the continued influence of the so-called ‘White Australia Policy,’ which sought to maintain Australia as an “outpost of the British race,” NAA, Speech by John Curtin (1941), A989, 1944/43/554/2/1 part 1. as then Prime Minister John Curtin (1885–1945) phrased it in 1935. Jewish immigrants, particularly those from Eastern Europe, faced widespread prejudice and antisemitism. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, public debates frequently portrayed them as an economic threat. Antisemitic stereotypes that depicted Jews, moreover, as unpatriotic outsiders were promoted in certain press outlets and circulated in certain social circles, leading to discrimination and hostile treatment. The Prague-born journalist and writer Egon Erwin Kisch (1885–1948) experienced this for himself. In 1934, he was invited to Melbourne as a delegate to an anti-war congress. Despite his valid visa, Australian authorities denied him entry and had him arrested when he attempted to disembark, although he was released on bail following high-profile protests. Kisch later documented his experiences in the book Australian Landfall, first published in 1937.

On 6 December 1938, a group of Yorta Yorta people, led by William Cooper, marched on the German consulate in Melbourne, planning to deliver a petition to the German consul, Walther Drechsler (1880–1961). This group from the Australian Aborigines’ League, representing Indigenous people who were themselves not recognized as equal citizens by the colonial government of their homeland, expressed its full-throated protest against “cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi government in Germany’.” NAA, William Cooper Petition, https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/william-cooper-a-koories-protest-against-the-nazis/6imrknr02. The petition aimed to notify the German “government and its military leaders that this cruel persecution of their fellow citizens must be brought to an end.” Although Cooper’s petition in response to the ‘Kristallnacht’ pogroms of November 1938 had little immediate effect, it was a powerful and remarkable show of solidarity. Seventy-four years later, on the same date, Cooper’s 84-year-old grandson, Alfred Boydie Turner (*1928), was able to symbolically complete his grandfather’s mission. On 6 December 2012, he handed over the original petition to the German honorary consul in Melbourne in a ceremony attended by relatives, friends, Shoah survivors, and other leading representatives of the Jewish community.

Fig. 6: William Cooper, founder and leader of the Australian Aborigines’ League, around 1937; Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=92402581.

Among the Jewish refugees who arrived in Australia during this period were several rabbis who would have a lasting impact on Jewish life in the country. One of them was Herman Max Sänger (1909–1971), who had previously served as a rabbi in Breslau (Wrocław) and Berlin. After fleeing to London, Sänger (later Sanger) was sent to Australia by the World Union for Progressive Judaism. His charismatic leadership reinvigorated the previously marginal Reform movement in Australia. Sanger’s approach, which paired a pro-Zionist viewpoint with a more liberal religious practice, while still upholding traditions such as kippah-wearing and a kosher diet, resonated with many Jewish immigrants who were familiar with this balance from the communities in their birthplaces. Like Sanger, the Breslau-born Rabbi Alfred Fabian (1910–1989) escaped to Australia in 1939 and became the chief rabbi of the Hebrew Congregation in Adelaide in 1946.

Jewish communities in Australia showed solidarity with refugees from Europe. Many individuals personally helped their relatives by writing affidavits and hosting them on arrival, or lent support through various aid organizations, such as the Jewish Welfare Society and the Jewish Welfare Relief Society. Starting in 1959, the latter society was directed by Edward Kurt Lippmann (1920–2000), a Hamburg-born refugee who had taken refuge in Australia in 1938. At the same time, opposition to Jewish immigration remained strong. The proposal by the Frayland-lige far yidisher teritorialer kolonizatsye (Yiddish: Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization, founded in 1935) to establish a settlement for Jews from Europe in the Kimberley region of Western Australia – a proposal known as the Kimberley Plan – was ultimately abandoned. Despite the efforts of some prominent Jewish community members, including the Russian-born lawyer and journalist Isaac N. Steinberg (1888–1957), the plan failed due to financial difficulties, logistical challenges, and a lack of support from both the Australian government and sections of the local Jewish community. Steinberg later wrote about these events in his book Australia, The Unpromised Land: In Search of a Home (1948).

The growing international concern over the plight of Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria led the United States to convene the Évian Conference in 1938 with the aim of agreeing on joint strategies for addressing the crisis. While the conference was ostensibly aimed at coordinating humanitarian assistance, most participating national delegations focused on protecting their own interests, leading to a predominantly restrictive stance on refugee quotas. The Australian government declared its willingness to accept 15,000 refugees over three years, but altogether only about 9,000 Jews from Central Europe found refuge in Australia before the outbreak of the Second World War. Among these refugees were Reinhold (1891–1985) and Erich Scholem (1895–1965), along with their mother, Betty Scholem (1866–1946), who arrived in Sydney by ship in 1938 and 1939, respectively.

After the war began in 1939, very few Jews from German-speaking Europe reached Australia. Those who did mostly arrived under very unpleasant circumstances. Around 2,000 Jewish refugees, classified as ‘enemy aliens’ by the British government, were transported from the United Kingdom to Australia aboard the SS Dunera and interned in camps upon arrival.

The immigration of Shoah survivors to Australia had a notable demographic and social impact on Australian society after 1945, particularly on the country’s collective memory. Between 1938 and 1961, the Jewish population of Australia grew from approximately 23,000 to 61,000. Many of the new arrivals were displaced persons (DPs) who had survived concentration camps and ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe or had fled to Shanghai during the war before seeking refuge in Australia. Between 1947 and 1952, as part of international resettlement programs, particularly through the International Refugee Organization, Australia took in tens of thousands of DPs, including many German Jews. However, the Australian government pursued a selective immigration policy that initially prioritized European refugees with desirable professional qualifications. Many Jewish DPs from Germany began new lives in cities such as Sydney and Melbourne that already had well-established Jewish communities. One of these immigrants was Magda Altman (1922–2015), who was born in Budapest and arrived in Australia in April 1949 on the SS Luciana Manara. The historian Georg Bergmann (1900–1979) from Lissa (Leszno) migrated to Australia via Austria in 1947. Bergmann (later George Bergman) actively supported other émigrés through his involvement with the New South Wales Jewish Board of Deputies and the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith. He also dedicated himself to documenting the history of Jewish migration to Australia.

Some of the refugees later became involved in Holocaust education and remembrance. One example is the German-Jewish journalist Ernst (later Ernest) Platz (1906–1969). Born in the town of Brühl, in the Rhineland, Platz was interned in Buchenwald concentration camp in June 1939. Nevertheless, he managed to escape with his wife Frieda Platz (1903–1996), and they arrived in Australia on 29 December 1941 aboard the Cape Fairweather. In Australia, Platz co-founded the Jewish Council to Combat Fascism and Anti-Semitism and worked extensively to preserve the memory of the German-Jewish community in Australia. His publications, such as A Monograph Concerning German-Jewish Migrants:From the Foundation of the Colony of Victoria and New South Wales to the Present Time (1964), advocated for Holocaust remembrance, the fight against antisemitism, and for solidarity with Australia’s Indigenous peoples.

Around 2,500 Jewish refugees arrived in Australia after the war from Shanghai, where some 18,000 German-speaking Jews had sought refuge following the Nazi takeover. Among them was the Berlin-born journalist Fritz Friedländer (1901–1980), later Friedlaender. After his release from Sachsenhausen concentration camp, he made it to Shanghai in March 1939, where he taught adult education classes for émigrés and was active in the Union of Democratic Journalists. Upon his arrival in Australia in 1946, Friedländer initially worked as a manual laborer before becoming a freelance journalist for the Australian Jewish News.

The Shoah survivors brought with them their diverse experiences and the trauma of persecution, which led to the development of a distinct culture of remembrance in Australia. Memorial sites, commemorative events, and educational initiatives were often initiated and led by survivors. Today, this history is preserved and conveyed through institutions such as the Sydney Jewish Museum and the Melbourne Holocaust Museum, which was founded by survivors and remains central to Holocaust education in Australia. These and similar institutions promote an approach to collective memory that not only recognizes the unparalleled Jewish suffering during the Second World War but also promotes human rights and the fight against antisemitism and racism.

Today, no notable German-speaking Jewish diaspora remains in Australia. Although this group of Jews had roots there extending into the early nineteenth century, their history remains largely unknown to both scholars and the general public.

The Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal: https://collections.ajhs.com.au/Journal/Index

The Australian Dictionary of Biography (including numerous Jews): https://adb.anu.edu.au/

The State Library of New South Wales, “Australian Jewish Community and Culture,” photo database: https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/australian-jewish-community-and-culture

Dunera: Stories of internment, online exhibition on the so-called Dunera Boys: https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/exhibitions/dunera-stories-internment

Podcast Jüdische Geschichte (Chair of Jewish History and Culture at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich – episode 40 “Jewish Convicts“ and episode 41 “Far from Home: Jewish ‘Enemy Aliens’ in Australia”: https://cast.itunes.uni-muenchen.de/vod/playlists/bF2u8gdUr6.html

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Julia Schneidawind is a historian and Assistant Professor at the Chair of Modern Jewish History and Culture at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Her research focuses on German-Jewish cultural and migration history, material culture studies, exile history, and women’s and gender history. Her dissertation, Schicksale und ihre Bücher. Deutsch-jüdische Privatbibliotheken zwischen Jerusalem, Tunis und Los Angeles, was published by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in 2023 and awarded the Eduard Dukesz Prize the same year. She is currently working on her habilitation project, which explores the everyday history of violence against women in the German-speaking world during the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century.

Julia Schneidawind, From Altona to Melbourne. German-Speaking Jews in Australia (translated by Jake Schneider), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-9> [January 30, 2026].