Born on January 16, 1897 in Lublinitz, German

Empire (today Lubliniec, Poland)

Died on September 15, 1998 in London, England

Occupation: Historian, sociologist, Director of Research at the Wiener Library

Migration: Great

Britain, 1939

“I am no longer a German, I will never be an English woman […] I am a former German

Jewish woman of British nationality – a somewhat complicated phenomenon whose multiple,

mutually overlapping loyalties, struggling to find balance, sometimes almost make me

feel anxious.” Eva G. Reichmann, “Im Banne von Schuld

und Gleichgültigkeit (1960)“, in: Reichmann, Größe und Verhängnis

deutsch-jüdischer Existenz. Zeugnisse einer tragischen Begegnung. Lambert

Schneider: Heidelberg, 1974, 173.

“Eine Deutsche bin ich nicht mehr; eine Engländerin werde ich niemals sein […] Ich

bin eine ehemals deutsche Jüdin britischer Staatsangehörigkeit – eine etwas

komplizierte Erscheinung, vor deren vielfältigen, sich überlagernden und sich um einen

Ausgleich ringenden Loyalitäten mir manchmal selbst fast bange werden möchte.“

The prolific historian and sociologist, Eva Gabriele Reichmann (née Jungmann), wrote these poignant words in her

essay, “Under the Spell of Guilt and Indifference” [Im Banne von Schuld und

Gleichgültigkeit], published in 1960. Fleeing Nazi persecution, she was forced to leave

Berlin in 1939 for

London with her

husband, the jurist Hans

Reichmann (1900–1964). She remained in England until her death at age

101. An academic who worked outside the academy largely due to forced migration, sexism

and patriarchal structural limitations, Reichmann nevertheless contributed significant

scholarship on the history of antisemitism and the German Jewish experience. Although

she described her relationship to Germany as “complicated,” she staunchly retained her German language,

identity and commitment to German Jewish culture during her postwar life and work in

Britain. Reichmann returned to Germany many times after the

Second World War to support reconciliation and interfaith dialogue.

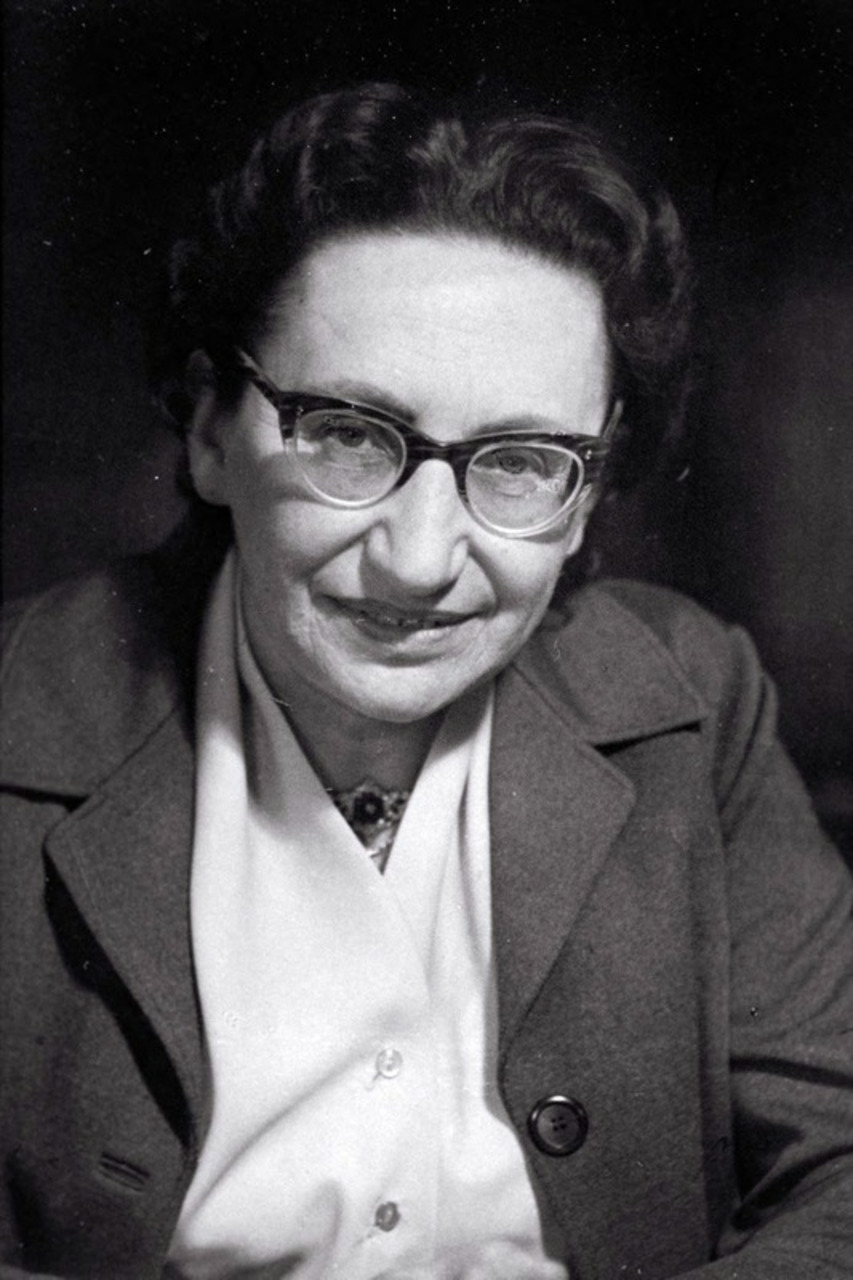

Fig. 1: Eva Reichmann by Lotte Meitner-Graf, undated, Eva Reichmann Collection AR 904, F 3700, Leo Baeck Institute.

Born in Lublinitz (Lubliniec) in Upper Silesia, Eva Reichmann grew up in a liberal, acculturated yet religious home. Her immediate family consisted of her father, Adolf Jungmann (1859–?), who was a lawyer; her mother Agnes Jungmann (1866–1942), née Roth, who would later be murdered in Theresienstadt ghetto during the Shoah; and her two siblings, Otto Jungmann (1890–1950) and Elisabeth Jungmann (1894–1958), who both later emigrated to Brazil and England, respectively. When Reichmann was a young child, her family moved to Oppeln (Opole), where they became close to the preeminent Rabbi Leo Baeck (1873–1956). Later she emphasized how important and influential Baeck was on her religious, professional and personal life, a man she later called the ‘symbol of German Judaism’. After studying economics and sociology in Breslau (Wrocław), Berlin, and Munich, and remarkably in 1921, she earned her doctorate at Heidelberg University, which was among the first universities in Germany to allow women to study from 1900.

Turning to communal work, Reichmann joined the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith in Berlin (Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens). From 1893, the CV was an important organization that fought for the rightful place of German Jews within German society, their civil rights, and against rising antisemitism, including through legal means. Although she was sympathetic to Zionism and the intellectual challenges it held for German Jewry, Reichmann firmly believed in the importance of the Jewish diaspora as a legitimate and positive ‘Jewish path’, one that she saw not in a negative light or as a sign of the decline of Judaism, but that had value and purpose in its own right.

Reichmann began to work for the CV on cultural policy and public debate. From 1933, she became the editor of Der Morgen, its cultural magazine that focused on a range of issues of Jewish interest, especially concerning German Jewish life under the rise of the Nazis. The CV not only shaped her professional life, but also her personal circumstances: here, she met Hans Reichmann, who worked as a lawyer for the association and became her husband. Reichmann came from a Jewish family in Hohensalza (Inowrocław) and later initiated an anti-Nazi propaganda campaign in the last phase of the Weimar Republic. Eva Reichmann also worked for the Jewish Agency in Berlin as well as the Reich Representation of German Jews (Reichsvertretung der Deutschen Juden), led by Leo Baeck, which served as an umbrella organization to coordinate Jewish groups in Germany from 1933. In 1937, she reported on a study trip to Mandatory Palestine in the CV newspaper C.V.-Zeitung, in which she praised the success of Jewish settlement and construction, yet also confirmed her view that Palestine was not a solution for everyone, as it could not absorb all Jews who were seeking a new homeland.

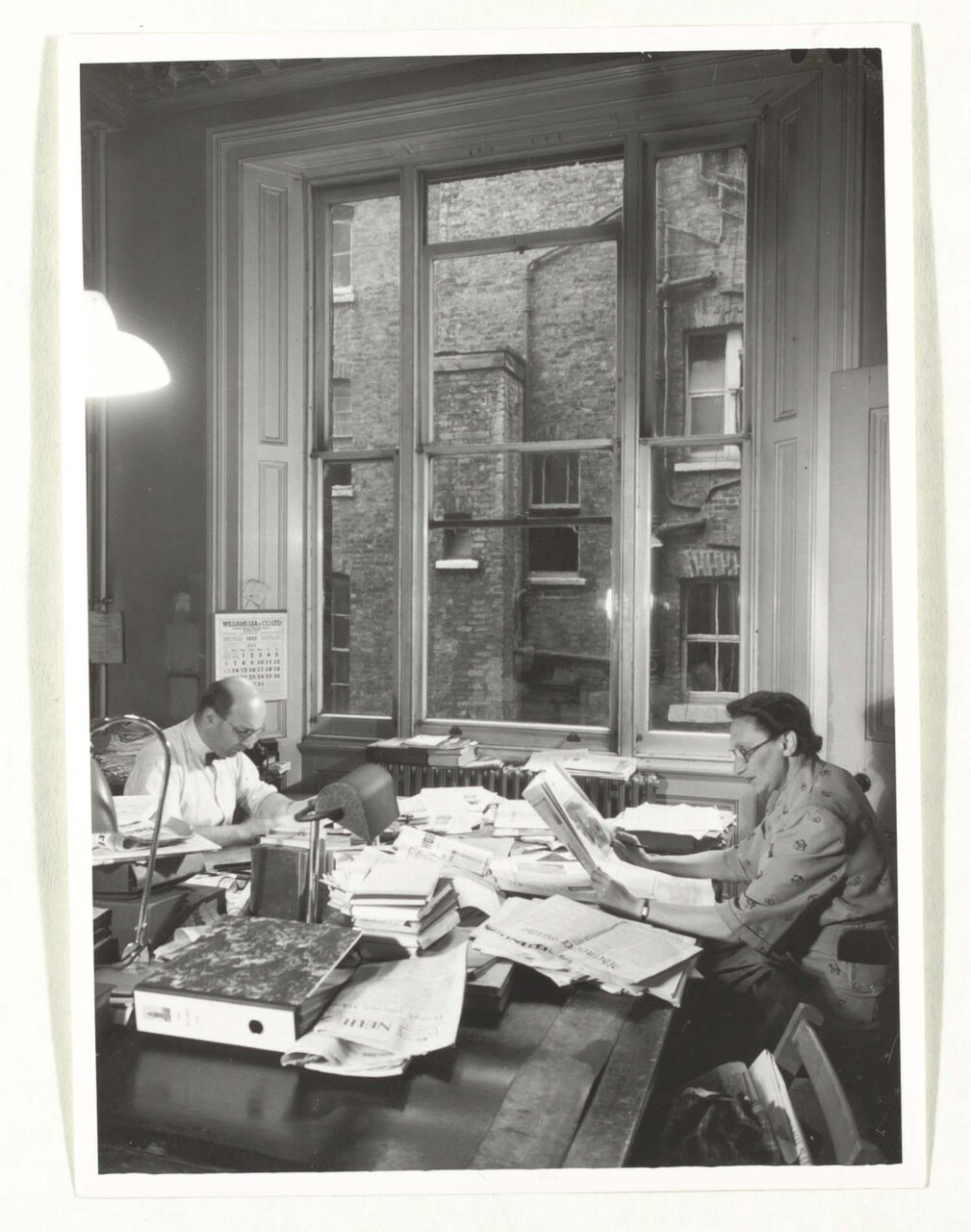

Fig. 2: Eva Reichmann in the Wiener Library, London, mid-1950s; Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

Reichmann’s commitment to remaining in Germany was shaken with the arrest of her husband after the November Pogroms in 1938, during which he was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. After she arranged his release on condition that the couple would emigrate, they settled in London in straitened financial conditions. Like many other German-speaking Jewish refugees – men and women alike – after Britain’s entry into the war, Hans Reichmann was then temporarily interned at the Onchan Camp on the Isle of Man as a German ‘enemy alien.’ For her part, Eva Reichmann began to work for the BBC Monitoring Service as a translator, briefly becoming the main breadwinner of the couple as did many other middle class Jewish refugee women who adapted readily to their new living situation. Like many Jewish refugees who remained in Britain, in 1945, she became a British citizen.

In exile, Reichmann maintained a significant intellectual link to German scholarship. She continued her studies at the London School of Economics (then in Cambridge), which resulted in her monograph Hostages of Civilisation, published in English in 1950. The book was published six years later in German as Flucht in den Hass: Die Ursachen der deutschen Judenkatastrophe and earned her a second doctorate. Commentators noted how impressed they were by the fact that someone who had survived Nazi persecution, whose husband had been in a concentration camp, and whose mother had died in Theresienstadt ghetto, was able to write so dispassionately about the history of antisemitism and the rise of Nazism.

Fig. 3: (left to right) Susanne Rosenstock, Hans Reichmann, Ilse Wolff, Alfred Wiener, Eva Reichmann and Werner Rosenstock, undated (1950s), London; Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

From 1945, Reichmann worked as the first Director of Research for the Wiener Library, joining her former CV colleague, Alfred Wiener (1885–1964), the Library’s founder and namesake. Wiener, Reichmann, and other German Jewish colleagues endeavored to build a research institution based on pre-war and wartime collecting efforts of the predecessor organization to the Wiener Library, the Jewish Central Information Office. Wiener had fled Nazi Germany in 1933 and carried on collecting and information dissemination activities from the Netherlands before moving to London in 1939. The institution continued to provide evidence during and after the Second World War, including to support evidence-gathering for war crimes trials and to promote new research on the rise of the Nazis and the Shoah. With the appointment of Reichmann as research director, several initiatives emerged that solidified the institution as an important early documentation center.

Reichmann aimed to fill gaps she perceived in the evidentiary record, particularly with regard to the voices of the victims. Building on her work, experience, and networks of Jewish communal defense, she helped create a large archival collection of eyewitness accounts of Jewish and other survivors of the Shoah for the Wiener Library, among a number of other important research initiatives. She held the position of Director of Research until 1959. Reichmann also served on the executive of the Leo Baeck Institute, founded in the late 1950s in London, and was a member of the Belsize Square Synagogue, a largely German-speaking Reform Jewish congregation in London. She and her husband were both members of the Association of Jewish Refugees; her husband served as Chair for more than ten years, while Reichmann was very active in London’s German-speaking Jewish community.

Fig. 4: Eva Reichmann by Laelia Goehr, undated; Eva Reichmann Collection, AR 904, F 2878, Leo Baeck Institute.

Reichmann often traveled with Alfred Wiener to West Germany to promote interfaith dialogue, to give lectures and to speak to student groups, eschewing the concept of collective guilt despite her personal experiences, although returning to Germany permanently after the war was out of the question. She continued to write and publish on the history of German Jewry and legitimacy of the German Jewish diaspora, defending the emancipation of Jews in Germany against any insinuation of its failure. Many of her most important writings were collected and published in two volumes in German in 1974 (Grösse und Verhängnis deutsch-jüdischer Existenz. Zeugnisse einer tragischen Begegnung).

In 1983, the Wiener Library published a special edition of its periodical, The Wiener Library Bulletin, to mark its 50th anniversary. In it was Eva Reichmann re-printed short essay titled “Alfred Wiener – The German Jew,” which, although ostensibly about her former director, contains much that might equally apply to her. In particular, she reflects on Wiener’s views of post-war Germany, rooted in his high regard for church opposition to the Nazis and “the heroes of the Resistance,” which represented the “other Germany, the better Germany, that Germany with which he had always identified himself.” Eva G. Reichmann, “Alfred Wiener – The German Jew,“ in: The Wiener Library Bulletin, Special Issue 1983: 50 Years of the Wiener Library, 10–13; originally published in The Wiener Library Bulletin XIX, no 1 (January 1965): 10–11 to mark the one year anniversary of Wiener’s death. That drive from the concept of the “other Germany” propelled her legacy and commitment to German Jewish culture and scholarship forward, and her work was recognized through many awards, including the Bundesverdienstkreuz First Class in 1969, the Buber-Rosenzweig-Medal in 1970, the Moses-Mendelssohn-Prize in 1982 and, in 1983, the Grosse Bundesverdienstkreuz (Grand Cross of the Order of Merit).

Short Biography of Reichmann on Testifying to the Truth: Reichmann – Testifying to the Truth

Biographical entry on Eva Reichmann at the Jewish Women’s Archive: Reichmann – Jewish Women’s Archive

The Eyewitness Accounts Collection is available via: WHL Collections and Testifying to the Truth

Kirsten Heinsohn, „,Also, ich bin eine Deutsche nicht mehr, eine Engländerin werde ich nie sein.’ Erfahrungen und Deutungen einer emigrierten Wissenschaftlerin”, in: Themenportal Europäische Geschichte, 2019. www.europa.clio-online.de/essay/id/fdae-1718

Christine Schmidt, “Eva G. Reichmann and Holocaust Scholarship,” in: Eastern European Holocaust Studies, vol. 3, no. 2 (2025), 433–442: doi.org/10.1515/eehs-2025-0003

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Christine Schmidt (https://christineeschmidt.com/) is the Deputy Director and Head of Research at The Wiener Holocaust Library in London, where she oversees academic programming, curates exhibitions, and leads on research partnerships. Her research has focused on the history of postwar tracing and documentation efforts, the concentration camp system in Nazi Germany, and comparative studies of collaboration and resistance in France and Hungary, and she is currently writing a social history of the Wiener Library’s postwar collecting of eyewitness accounts led by Eva Reichmann.

Schmidt has recently published articles in the Journal of Transport History, the European Review of History, American Imago, Culture Unbound, and The Journal of Holocaust Research, and is co-editing Letters and the Holocaust: Methodology, Cases, and Reflections (Bloomsbury, 2025); Survivors of Nazi Persecution - Beyond Camps and Forced Labour (Palgrave, 2024) and Older Jews and the Holocaust (Wayne State UP, 2026).

Christine Schmidt, Eva G. Reichmann (1897–1998), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-4> [February 03, 2026].