The city of Shanghai, and China more broadly, became an unlikely but important site of refuge for Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. By the time most of the approximately 15–18,000 German and Austrian refugees began to arrive, China was already at war with Japan, which occupied parts of the semi-colonial city of Shanghai. It was this liminal status, that of being not fully under the control of any one government, that created the opening that allowed the relatively free entry into the city until August 1939. At that time, Shanghai was one of the last open ports for Jewish refugees in the world. Additional migrants and refugees moved in and out of China after that point until December of 1941, when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor locked everyone in place until the conflict ended in 1945. Though the refugees did not choose China, they built a vibrant community in Shanghai full of cultural and social opportunities.

Judaism likely arrived in China by way of the Silk Road trading route around the time of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 C.E.). One remnant of this time is the Kaifeng Jews — an ethnically Chinese community that identifies as Jewish but does not practice a recognizable form of Judaism today. More recently, the era of Western colonialism in the nineteenth century spurred the emigration of a number of Sephardic Jews from Iraq. Much of this population settled in India, but some families sent trade representatives to the rapidly internationalizing city of Shanghai after the Opium Wars (1839–1842, 1856–1860). No single Western nation ever completely colonized the country of China, but many of the major players in Asian colonization set up concessions and trade companies in China.

Shanghai, once a sleepy village on the Huangpu River, transformed into a major international trading port in the space of a few decades. Residents from fourteen favored nations enjoyed extraterritorial rights, and even more nations were represented among the population. Some of the most prominent players included Iraqi Jewish families like the Sassoons, Kadoories, and Hardoons. By the early twentieth century, Shanghai had emerged as a city under semi-colonial status. There was an international settlement along the river run by a Municipal Council that included representatives from the British and American businesses that dominated it, a French Concession controlled as an outpost of France, and several poorer suburbs of these central areas under the control of local Chinese officials.

Pogroms in Imperial Russia in the early twentieth century, along with the Russian Civil War (1918–1920), resulted in a groundswell of Jewish migration into China. Most of this migration initially settled in China’s northeast, centering around the city of Harbin, with its distinctly Russian character and influence. The Japanese invasion of China’s northeast in 1931 led many Jewish refugees to leave Harbin for Tianjin or Shanghai.

When German and Austrian Jewish refugees began to arrive in Shanghai in the 1930s, the city had existing Jewish communities, synagogues, cemeteries, and schools. The Sephardic and Russian Ashkenazi Jewish populations helped to receive Central European refugees, planning for housing aid and vocational support. Although a steady trickle of refugees arrived throughout the 1930s, the trickle became a deluge in late 1938, after the events of both the ‘Anschluss’ and the November pogroms led to mass arrests, the loss of homes and businesses, and an untenable situation for Jewish residents living under Nazi rule.

In Vienna, a consul with the government of the Republic of China named Ho Feng-Shan (1901–1997) began to issue visas for Shanghai to help Jewish nationals prove they had a destination so they could leave Austria. The visas were not needed to enter the city, but they might have facilitated the emigration of some Austrian refugees to destinations around the world, including China.

In December of 1938 and the first months of 1939, the number of Jewish refugees arriving in Shanghai from Germany and Austria skyrocketed. Refugee aid societies already existed in the international concessions of Shanghai, which had seen an influx of approximately 25,000 Jewish and White Russian refugees from the newly founded Soviet Union and several hundred thousand Chinese refugees after the Japanese attack on eastern China in 1937. In a city with a population of around three million, around a quarter were refugees in 1939.

At the time Central European Jewish refugees fled Nazi rule, Shanghai was one of the only open ports in the world accepting them without requiring extensive paperwork or financial means. It earned this distinction because the war had already begun in China. The Japanese invasion of 1937 ended Chinese influence over passport control and created a period of time in which immigration was wholly unrestricted.

Fig. 1: Barbed wire barricades and sandbags in Shanghai, around 1937. Photo by Suse Schauss, entitled Drahtverhaue in den Strassen Shanghais. (Barbed wires in the streets of Shanghai.); courtesy of Sonja Mühlberger.

Initially, neither the Japanese authorities nor the Shanghai Municipal Council put qualifications on entry. As the number of refugees arriving with each passenger ship rose, and fears of strained resources increased, a groundswell of support for limiting or ending the refugee stream developed. Compelled by the coercion of the Nazi regime, Jewish refugees departed Europe, usually traveling by train through Fascist Italy to reach ports of departure. In Shanghai, Japan continued to hold a part of the International settlement known as Hongkou, where new arrivals were most likely to find housing. All three Axis powers did not attempt to stop the exodus of refugees to Shanghai, and indeed often facilitated it.

Shanghai was not a first choice for most refugees; it was the only choice. New arrivals from Central Europe, like future U.S. Treasury Secretary Michael Blumenthal (*1926), recalled that Shanghai had a reputation for lawlessness and a clear divide between the rich and the poor. Some refugees did not even know that much. Eva Gottheiner (1921–?) from Breslau (Wrocław) remembered that when she learned their destination, she “didn’t know what Shanghai was,” and her mother sobbed uncontrollably. Common laments among the new arrivals included the heat and humidity, the dire poverty of many indigent Chinese, and the stark contrast between the city’s richest and poorest residents.

The Western powers, led by the British, Americans, and French, were the ones to begin frenetic efforts to stop the flow of refugees. Though not high in number, indigent European migrants upset the colonial economy. Refugee Ernst Heppner (1921–2004), who had fled Nazi Germany in 1939 together with his mother recalled that the refugees were willing to do jobs for wages much lower than traditional ‘Shanghailanders’ (a term initially referring to the foreign population of the city). Rising housing and food costs, and the uncertainty of the war, added additional strains. Internationally-minded Jewish organizations like the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) and HICEM also began to try to stop the movements, expressing concern that the European refugee population in Shanghai was growing far beyond the means to support it.

Fig. 2: Ilse Krips, née Herzfeld, with her daughter Sonja at the window of their small apartment in Shanghai, around 1940. Bamboo poles were used to dry clothes and bed sheets; courtesy of Sonja Mühlberger.

On August 9, 1939, the Shanghai Municipal Council put into place its first restrictions on immigration into Shanghai. The restrictions concentrated on halting migration from the source, with the assistance of German and Italian officials and the shipping lines, by announcing that refugees would not be permitted to land in the International Settlement. Japan also required the registration of all Jewish refugees living in the Hongkou district. While allowing those already en route or about to embark to land, the restrictions limited future arrivals to refugees who could provide proof of a U.S. Dollar 400 deposit in the bank or a job earning a living wage waiting for them. The goal was to limit the number of indigent refugees who would need significant financial support.

By September 1939, the landscape in Europe was also changing rapidly. The surprise German invasion of Poland created new urgency to flee, but by June of the following year, the war had spread more generally to include Italy and Western Europe. As a result, travel routes for refugees were disrupted. A trickle of German-Jewish refugees departing Europe with their eyes on Shanghai as a destination continued for another year, now making the much longer trip through Eastern Europe and across Siberia into northeast China. As German interests turned east, Eastern European Jews also sought means to flee. The eastern escape route effectively ended with the German attack on the USSR in June 1941.

As the number of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany in Shanghai approached 20,000, they posed significant challenges for the approximately 6,000 Jews living in Shanghai before the war. Sir Victor Sassoon (1881–1961), a Sephardic Jew, built upon his father and grandfathers’ trade in cotton and opium from India to accumulate a vast fortune. Sassoon initially designated a large apartment and office complex known as the Embankment Building just north of Suzhou Creek as a refugee reception center. As refugees arrived in mid-1938, they would be received by representatives and brought to the building for temporary food and shelter. Still, refugee relief required funds to feed, clothe, and house so many.

Three major committees were developed to attend to the basic needs of the refugees. Dutch businessman Michel Speelman (1877–?) founded the Committee for Assistance of European Refugees in Shanghai (CFR). Speelman engaged in extensive fundraising efforts, and the CFR provided direct aid to refugees in 1938. The International Committee for Granting Relief to European Refugees was led by Paul Komor (1886–1973), a Hungarian businessman and diplomat. The International Committee (or ‘Komor Committee’) received most of its funding from Victor Sassoon. In addition to helping with housing and employment, it registered refugees and provided alternate travel cards to replace now-invalid German passports.

The Shanghai Municipal Council did not set up its own formal aid committee, but it did lease buildings from the Chinese government to be used by others to house and feed the refugees. Ultimately, there were six refugee camps for Jewish refugees, with the largest being the Ward Road Camp in Hongkou. The ‘Heime’, as the camps were known, provided not just beds, but soup kitchens used by refugees beyond those housed in the camps, as well as schools and hospitals for the Jewish refugees. The International Committee funded these operations with donations from the existing Sephardic and Russian Ashkenazi Jewish population of Shanghai, as well as funds wired from the JDC. Additionally, Sassoon endowed a special fund for the purpose of helping refugees set up businesses or gain vocational training that would enable them to work in the Shanghai economy.

Fig. 3: Sonja Mühlberger on her first day at school in Shanghai, 1945. The language of instruction at the Shanghai Jewish Youth Association (‘Kadoorie School’) was English; courtesy of Sonja Mühlberger.

Another prominent Shanghai Sephardic Jewish family, the Kadoories, also provided assistance. Sir Horace Kadoorie (1902–1995) followed in the footsteps of his uncle Sir Ellis Kadoorie (1865–1922) and set up the Shanghai Jewish Youth Association (SJYA). The SJYA educated up to 600 refugee youth at a time, in addition to providing meals, sports, and social activities for refugee children. Sonja Mühlberger (neé Krips) was born in Shanghai in 1939 to German refugee parents, and she attended the school as a young child between 1945 and 1947. Alongside her classmates, Mühlberger learned English and other basic subjects at the school.

All of these refugee organizations were born of the emergency of the sudden influx of Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria. They were led by businessmen who, for the most part, operated them with the skills they employed in their regular work. This made for an at times chaotic administration. In 1941, the JDC dispatched its own social worker, Laura Margolis (1903–1997), who worked to ease tensions between the various community and aid organization leaders to use their resources in the best way possible.

Refugees in Shanghai connected with the larger German-Jewish diaspora through news wires and letters. German-Jewish newspapers carried stories from the United States and Europe, and letters from friends and acquaintances still in Europe kept them abreast of the latest developments in the war. In October 1941, as the Nazis halted Jewish emigration from Germany, the source of these letters dried up. By 1943, there was an ominous lack of information in Shanghai, as letters from Nazi Germany stopped coming and the Japanese military increasingly censored the news coming across the wire services.

Living and working in the International Settlement of Shanghai required some degree of proficiency in English, the lingua franca of the globalized city. Many German-Jewish refugees had some training in English in school before departing Europe, and others found opportunities to learn once in Shanghai, such as at the Kadoorie School. Few refugees learned any Chinese, either Mandarin or the more common local Shanghai dialect. The older generation had very little contact with the Chinese population. Some of the younger generation – those born in Shanghai or who arrived as children – picked up some of the language. Blumenthal recalled learning some basic Shanghaiese from rickshaw drivers and vendors. Hans Cohn (1926–2020) from Berlin, who arrived in Shanghai at the age of twelve, also recalled that he picked up some Chinese, but that few of the refugees did.

Despite any elements of survival being contingent on the ability to negotiate the city in English, refugees most often spoke German to each other, and the language culture was visible in their cultural life. German language newspapers and periodicals formed a centerpiece of community life. The Shanghai Jewish Chronicle was published from 1939 to 1945, and continued after the war briefly as the Shanghai Echo. It reported on events both near and far, though international news received scrutiny from Japanese censors. Other newspapers such as Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt (1938–1943) reported on community life in Shanghai. The semi-monthly journal Gelbe Post (1939–1940) was dedicated to East Asian culture alongside Jewish life in Shanghai, and Der Kreis (1941) provided information on the arts. Dozens of such publications sprang up and faded away during the war, usually as funding to print them permitted.

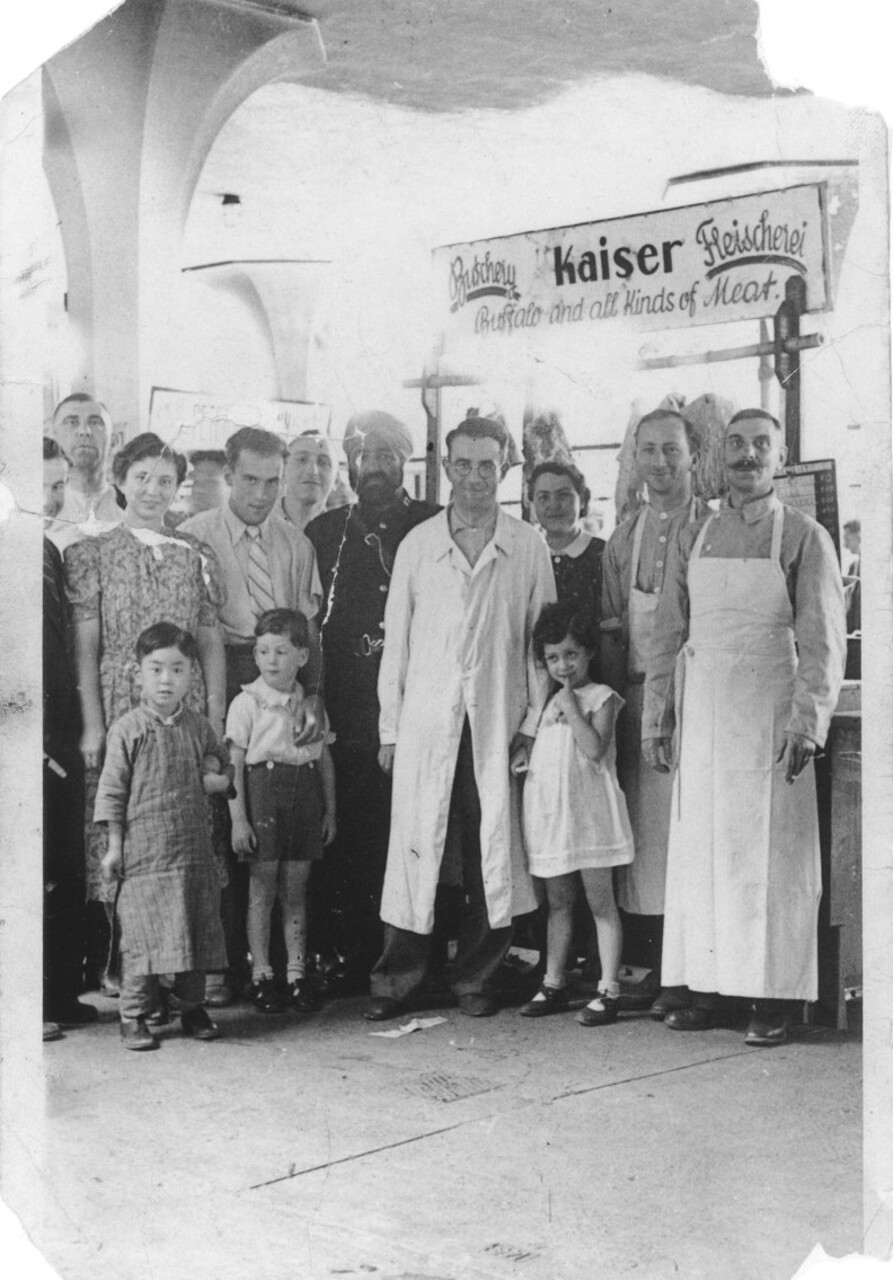

Fig. 4: German-Jewish refugees with local residents in Siegfried Kaiser’s butcher shop in Shanghai. Among those pictured is Kaiser (second from the right); United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Sonja Kaiser Kirschner.

Refugee musicians, artists, and performers, including pianist Karl Steiner (1912–2001) from Vienna and composer Wolfgang Fraenkel (1897–1983), brought Austrian classical music to local venues such as the Lyceum Theater and the Jewish Club of Shanghai. Siegfried Kaiser, who had fled Frankfurt with his wife and daughter in 1939 after he was arrested and sent to Dachau concentration camp, opened a small butcher shop in Shanghai. Kaiser managed to keep making and selling sausages even after he moved with his family to the designated area (ghetto). Shopkeepers and restaurant owners habitually established their credentials for their refugee audience by listing their previous addresses in their former hometowns. An area of Hongkou along Houshan and Zhoushan roads developed so many German and Austrian-style coffeehouses, shops, and restaurants that it came to be known as ‘Little Vienna.’ One of the most famous, the White Horse Inn (Café Weißes Rössel), was opened by Austrian refugee Rudolf Mosberg (1892–1959) and his wife and became a favorite meeting place every day from noon to midnight.

Restaurants, cafes, and home cooks all tried to recreate favorite European foods for homesick refugees, though as the war continued, rationing, inflation, and limited supplies proved challenging.

Because refugees entered a city with a small but thriving Jewish population, Shanghai had multiple synagogues. Many of the most prominent were built by and for the Sephardic community. However, the Ohel Moshe Synagogue in Hongkou was founded by Ashkenazi Jews from Imperial Russia and Poland in 1907, and the building was erected in 1927 on Ward Road. Because the synagogue bordered the restricted area, it became not only a place of worship, but also a meeting hall. Hans Cohn had his bar mitzvah there, as did many other young men when they turned thirteen in Shanghai.

Between 1938 and 1941, when the majority of Central European Jewish refugees arrived, Shanghai existed in a kind of liminal space between war and peace. The war had already begun in China. Japanese troops had attacked Shanghai on their sweep toward the Chinese capital of Nanjing in 1937, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. Millions of Chinese citizens became displaced during the fighting, and refugees flooded into Shanghai’s international zones from the suburbs and across the Eastern seaboard. The Republic of China (ROC) government fled inland, following the Yangtze River first to Wuhan and finally settling in the city of Chongqing, far away from Shanghai and the coast.

Parts of the city were occupied by the Japanese, who sought greater influence on the Shanghai Municipal Council and among the Western Powers in charge. The fragile status quo of life in Shanghai was dramatically upended early in the morning on 8 December 1941 while most of the city slept. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had begun. Japanese troops marched into the International Settlement and began the process of rounding up citizens of Allied powers still in Shanghai and resettling them in internment camps. The mostly British and American citizens included some of the Sephardic Jewish families that represented old Shanghai, as well as the American social workers representing the JDC.

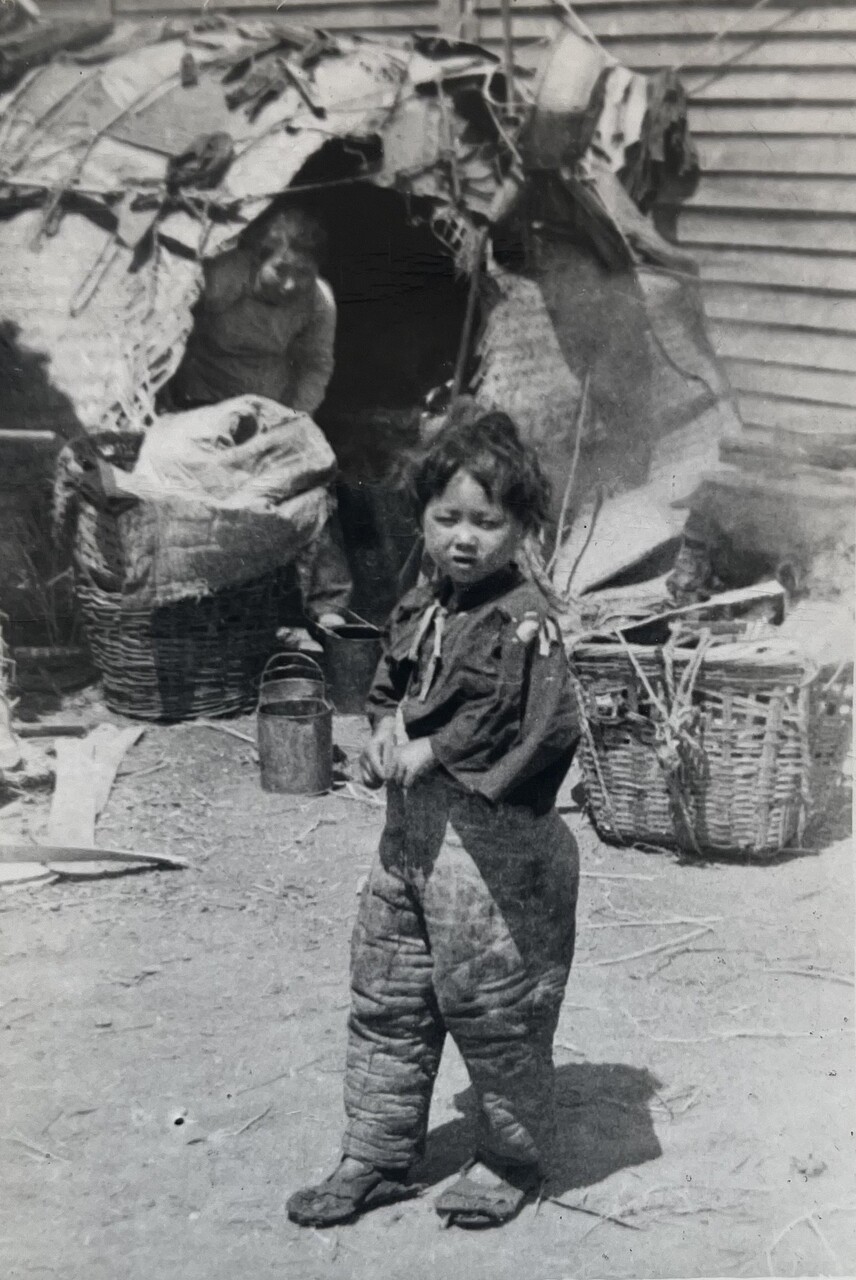

Fig. 5: Chinese refugees in the Hongkou district of Japanese-occupied Shanghai, around 1940. Many suffered from severe poverty, as shown in the photo by Genia Nobel; courtesy of Sonja Mühlberger.

After a year of uncertainty, on 18 February 1943, the Commanders of the Japanese army and navy in Shanghai released a proclamation that stateless refugees who had entered the city after 1937 would be required to relocate to a ‘designated area’ in Hongkou. The area consisted of a little under one square mile, in an area that housed several thousand European refugees already, as well as close to 100,000 Chinese. Refugees quickly termed the designated area the ‘Shanghai ghetto,’ though Japanese officials were careful to avoid the terms ‘Jews’ or ‘ghetto’ in their announcement.

Most German-speaking Jews remember this period as a time of hardship and uncertainty. With even fewer opportunities for employment than before, many refugees lived on soup kitchen rations of a single meal a day, with supplements for the very young or ill. Acts of desperation, such as turning to prostitution or engaging in hard labor more common to the Chinese ‘coolie’ population increased. Rumors spread that Nazi officials tried to convince Japanese military leaders to round up the Jewish population and destroy them. Access to food for the community kitchens and basic supplies for hospitals and shelters was hard to come by.

Fig. 6: A so-called coolie (pejorative term used for low-wage labourers of Chinese descent) in front of a rickshaw in Shanghai, around 1940. The rickshaw pullers mostly came from rural areas outside the city. They experienced poverty and long hours of work. Photo by Genia Nobel; courtesy of Sonja Mühlberger.

Refugees have different memories of life in the ghetto. One common defining characteristic was the feeling of having to move quickly and accept loss. Another was that of the bond they forged with other refugees for having lived through the experience of the ghetto. Refugees such as Hermann Krips (1910–1967), who worked outside the area, would be forced to request regular passes from the self-designated ‘King of the Jews’ in the ghetto, Japanese official Kano Ghoya (1901–1983). Ghoya chose to humiliate and abuse the refugees under his care at every opportunity, earning him enmity and resentment. Because many refugees had maintained ominous suspicions about what would come next, tensions in Hongkou proved high, and fear ran rampant.

Though dozens of Jewish refugees died from tropical diseases or other ailments, most survived the war. The fighting came closest to the refugee community when, in the last months of the war, the U.S. Air Force began an aerial bombing campaign against Japanese facilities in Shanghai. In an attempt to hit the Ward Road Jail, bombs fell into the Shanghai ghetto and killed 38 refugees. They were the only ones to die in the fighting. On 2 September 1945, the Japanese Government surrendered. Ghoya was driven from Hongkou by a mob of newly liberated refugees.

Few refugees who fled to Shanghai did so with the intention to stay. Although some may have considered settling in for the long term, most displaced German and Austrian Jews hoped for an opportunity to resettle abroad. In one JDC poll, 16 percent of the refugees expressed a willingness to repatriate to Europe. Often, they could not imagine restarting somewhere else. Sonja Mühlberger and her family were among them. According to records from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the International Refugee Organization (IRO), 3,141 German and Austrian displaced persons returned to Europe. More refugees conveyed interest in the Zionist project in Mandatory Palestine and departed for the State of Israel after 1948. The IRO reported that 5,112 Shanghai refugees resettled in Israel, though that figure may include some Russian Jews who fled to China before the Second World War. Ultimately, most of the German-speaking Jews in Shanghai hoped to wait on a quota visa for the United States or entrance to Australia.

Fig. 7: A Hongkew resident reads The Shanghai Herald in German, Shanghai, 1946. Photo by Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy of Arthur Rothstein Legacy Project.

With Japan defeated, the colonial era in China came to an end. The International Settlement and French Concession reverted to local control, and the Republic of China government controlled the entire city for the first time since its founding. In November 1945, the government of the ROC shocked the refugees by announcing the need for all foreigners in China to repatriate, including the refugees, who they claimed had entered as ‘illegal immigrants’, at a time when Chinese permission could not be obtained. International organizations like the UNRRA and the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees (IGC) sent representatives to negotiate with the Chinese government for more time to make plans for where Jewish refugees might go. When UNRRA and the IGC shut down in 1947, the IRO took over.

Though all three organizations used Shanghai as a base of operations for refugee work, they assisted people from all over China, including Jewish and White Russian refugees in Harbin and those who followed jobs with the U.S. military to Chongqing, Nanjing, or Kunming. Using U.S. quota visas and the new 1948 Displaced Persons Act, recruiting efforts by Australia for young adults, and a few emergency transfers of groups of refugees to Israel, the Jewish refugee population in China dwindled to a few hundred remaining in fall 1949, when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

CCP leaders in Shanghai appropriated the Ohel Moshe Synagogue in the Hongkou ‘ghetto’ that had played such a vital role in the faith life of so many Jewish refugees for a mental health hospital and later for use as a government storage facility. During the ‘Great Leap Forward’ economic plan at the end of the 1950s, all four Jewish cemeteries in Shanghai were transferred outside the city limits with the other foreign cemeteries, their tombstones eventually looted and locations largely lost.

In the 1980s, a group of survivors based in the United States bonded over the shared experience of finding refuge in Shanghai. They set up regular ‘Rickshaw Reunions’ to gather together refugees who were still surviving, and they established a quarterly review called the Hongkew Chronicle, published in English through the 1980s. Issues shared news about former Shanghai refugees, reprinted articles about their experiences from media all over the world, and shared short essays and photographs reminiscing about the war. In the letters to the editor, ex-refugees wrote in to offer their own memories and experiences, sometimes in contrast to others. After the United States and the PRC established diplomatic relations in 1979, the way was opened for refugees to return to Shanghai as visitors. Although these German-speaking Jews had not chosen China, Shanghai left an indelible mark on them and linked them together even as they resettled across the world. This was also reflected in the fact that they referred to themselves as ‘Shanghailanders’.

In 1994, a group of returning refugees met with Chinese officials and local Jewish leaders in Shanghai to discuss memories of their time there and the preservation of the synagogue and other relevant buildings. Though nearly all of the refugees had left China by the early 1950s, their presence lived on in the memories of the local residents and the buildings they left behind. A decade later, so many tourists had arrived to see the areas where the Jewish refugees lived that the Shanghai government altered its development plans to preserve a number of buildings as they were in the 1940s. The Ohel Moshe Synagogue reopened, and the local authorities began to explore the idea of a museum.

In 2007, the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum opened to the public. In the heart of the old Shanghai ghetto, the buildings surrounding the temple had housed hundreds of refugees, and the old Ward Road Heime was nearby. The sidewalks around the museum display special plaques that identify the area as the ‘Shanghai Ark,’ where ‘China’ saved 20,000 Jews from the Shoah. The story of the Shanghai ghetto, as a site of both exile and salvation, has become a means to unite thousands of so-called Shanghailanders and their descendants with China, with benefits for both the former refugees and Chinese public diplomacy.

Oral history interview with Eva Gottheiner, 1993. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Jewish Family and Children's Services of San Francisco, the Peninsula, Marin and Sonoma Counties: https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn515235

Thematic walk through Shanghai, developed by the research project Relocating Modernism: Global Metropolises, Modern Art and Exile (METROMOD). The walking tour connects sites of exilic artistic production: https://walks.metromod.net/walks.p/17.m/shanghai

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Meredith Oyen is an associate professor of history and an affiliate of the Asian Studies Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Her research explores how immigration, deportation, refugee policy, and transnational networks have shaped China’s relationship with the world, especially U.S.-China relations. Her current research on refugees in China after the Second World War has been supported by a research fellowship from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Oyen has published articles in Diplomatic History, the Journal of Cold War Studies, Modern Asian Studies, and the Journal of American Ethnic History, as well as peer reviewed chapters in Overcoming Empire in Post-Imperial East Asia (Bloomsbury), and Statelessness After Arendt: European Refugees in China and the Pacific during the Second World War (Manchester University Press). Her first book, The Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of U.S.-Chinese Relations in the Cold War, was published in 2015 by Cornell University Press.

Meredith Oyen, Free and Unfree in a Faraway Place: German-speaking Refugees in China’s Foreign Concessions and the Shanghai Ghetto, in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-26> [February 26, 2026].