Jeanne Mandello (1907–2001)

Born on October 18, 1907 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Died on December 17, 2001 in Barcelona, Spain

Occupation: Photographer

Migration: France, 1934

| Uruguay, 1941 |

Brazil, 1953 |

Spain, 1959

Arno Grünebaum (1905–1990) (artist name: Arno Mandello)

Born on October 9, 1905 in Fulda, Germany

Died in July 1990 in Salento, Italy

Occupation: Photographer, painter, sales representative

Migration: France, 1934

| Uruguay, 1941 |

France, ca. 1955 |

Italy, ca. 1968

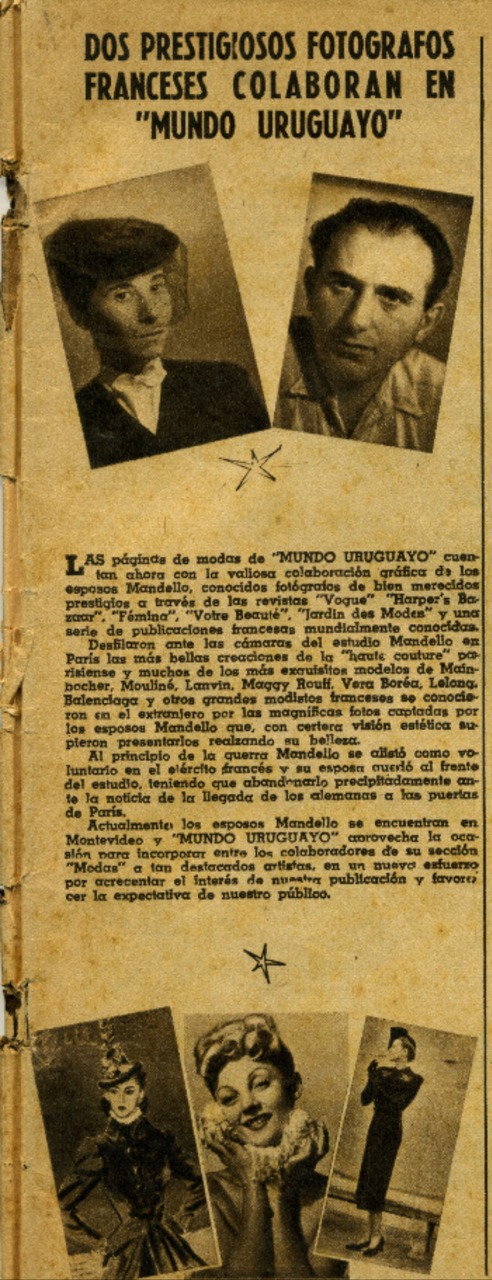

“Two renowned French photographers collaborate with ‘Mundo Uruguayo,’” “Two prestigious French photographers collaborate in ‘Mundo Uruguayo’”, in: El Mundo Uruguayo, no. 1257, 1943, 41 (all translations by the author). wrote the Uruguayan magazine The Uruguayan World in 1943. This referred to the two German-born, now stateless, Jewish refugees Jeanne and Arno Mandello. From early 1934 to mid-1941, the Mandellos had lived in France – until the outbreak of war in Paris – where they worked as photographers. But was this the only reason they introduced themselves as ‘French’ in Uruguay?

Fig. 1: Jeanne and Arno Mandello in Montevideo, around 1948; private collection © Isabel Mandello de Bauer.

Jeanne Mandello grew up in Frankfurt as Johanna Mandello in a secular Jewish family where religion played a negligible role. Although the Jewish holidays were celebrated, Christmas was as well. Like many other German-Jewish families of the urban, educated middle class, her family was acculturated. Mandello’s father managed a department store in the city, and her mother, who died early, strove to ensure her two daughters’ musical education. Mandello attended the Elisabeth Girls’ High School, where she sometimes participated in Protestant and sometimes Jewish religious classes.

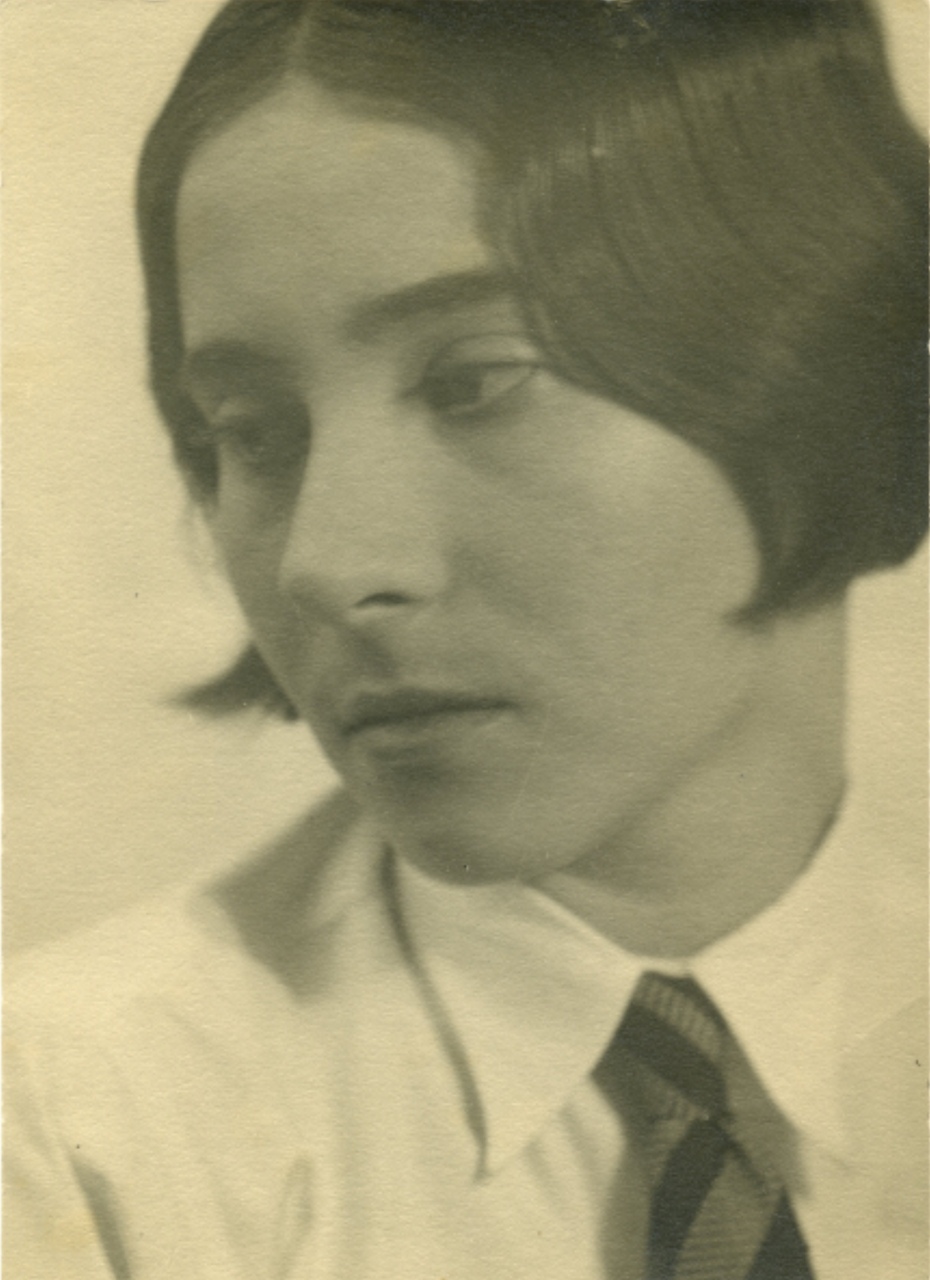

After graduating from school, she was allowed to train as a photographer and moved to Berlin, where she studied at the renowned Photography School of the Lette Association, which had been offering photography courses for women since 1890. It was there that Mandello adopted the look of the ‘New Woman.’

Fig. 2: Portrait of Johanna Mandello, photo by Nathalie von Reuter, 1930; private collection © Isabel Mandello de Bauer.

After an apprenticeship in the photo studio Wolff & Tritschler in Frankfurt and her graduation from the Lette school, Mandello and a former fellow student, Nathalie von Reuter (1911–1990), opened their own photo studio in Frankfurt. This was an increasingly common situation during the Weimar Republic; one example is Grete Stern’s (1904–1999) and Ellen Auerbach’s (1906–2004) Berlin agency ringl + pit.

When Mandello met sales representative Arno Grünebaum, born in Fulda in 1905, he not only became her partner and later husband, but she also trained him as a photographer. In later years, the two sometimes worked together, or Grünebaum secured commissions and Mandello took the photographs. Here, too, a new form of emancipation is evident, one that was common among many young women from middle-class families at the time.

Mandello did not mention during the two interviews Jeanne Mandello was interviewed in 1994 by Susanne Knöner for the Museum Folkwang (see the museum’s Photographic Collection in Essen, Germany). A second interview was conducted in 1997 by Mercedes Valdivieso for an exhibition dedicated to her work in Barcelona (reprinted in the exhibition catalog Mandello. Fotografías 1928–1997, Barcelona 1997). in the 1990s that she was Jewish. This did not seem to have played a role in her environment. And yet she married Arno Grünebaum, who also came from a Jewish family, and she undertook a photography project about Gumpertz’sche Siechenhaus, a Jewish institution in Frankfurt, that was for sick, old, handicapped, and poor people. It was also referred to as a ‘Jewish place.’ Although religion was unimportant to Mandello, her social and cultural environment – like that of many ‘assimilated’ Jews in Germany – consisted of numerous Jewish friends and acquaintances.

Mandello and her husband left Germany for Paris at the end of 1933, having recognized the danger posed by the Nazis. Firstly, they probably saw that Jews were now being avoided when it came to commissions, as was the case with the Frankfurt sister-photographers Nini (1884–1943) and Carry Hess (1889–1957), whose Frankfurter Theater contract was terminated for ‘racial reasons’ as early as 1933. Secondly, Jeanne Mandello later reported that she had been warned both by an acquaintance, the Social Democratic Party MP Erik Nölting (1892–1953), and by her uncle Richard Seligsohn (1874–?), who worked for an international record company.

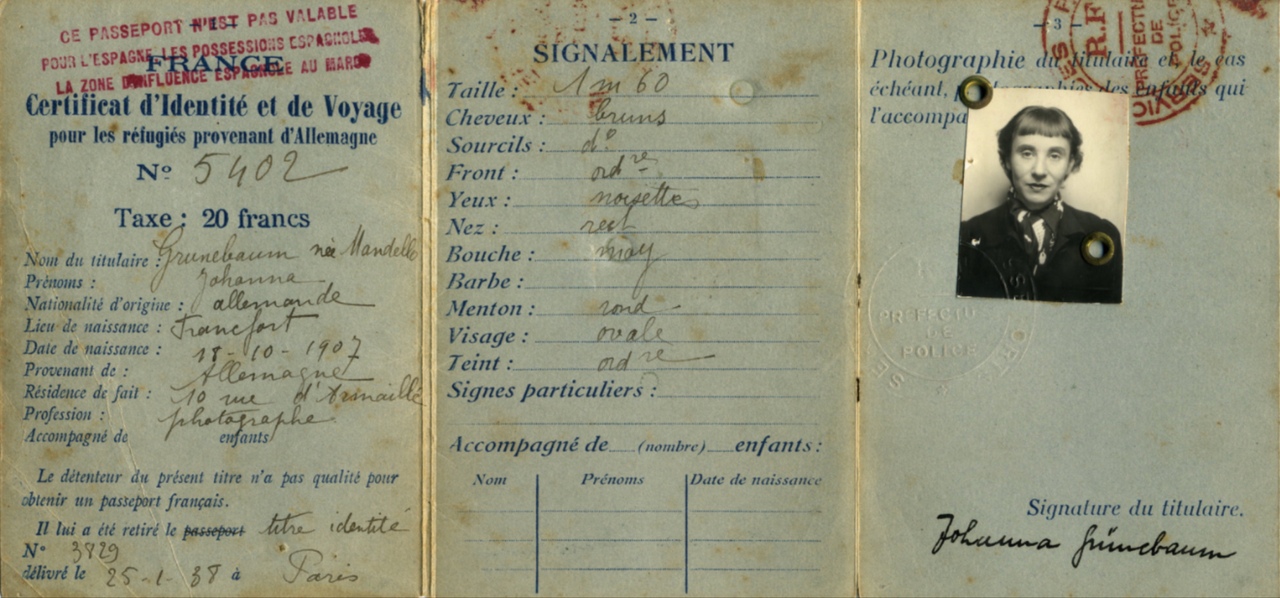

In Paris, the couple set up a photography studio and focused on their new life. Mandello later recalled many other German émigrés there, but she preferred to be close to the local population. Her rapprochement with French society was also reflected in her name. Mandello called herself, at least unofficially, ‘Jeanne’ instead of ‘Johanna,’ while her husband adopted her surname. ‘Mandello’ indeed worked in all languages and, unlike ‘Grünebaum,’ had no Jewish connotations. Whether this was a conscious or unconscious survival strategy remains an open question. Both probably did not want to be reduced to their Jewish ancestry, but rather to live freely and independently.

In Paris, which became a center of German-speaking artistic and political exile in the 1930s, the Mandellos moved in several, partially overlapping circles: Jeanne Mandello had French acquaintances from the fashion industry but also maintained friendships with German Jews such as the Munich photographer Hermann Landshoff (1905–1986). In this way, she created a network of mutual support and solidarity. Through contacts from her uncle Richard Seligsohn, the couple received their first commissions and made a name for themselves in the fashion industry, even receiving commissions from the Parisian fashion company Balenciaga in the renowned fashion magazine Vogue.

The war years must have been humiliating and deeply disappointing for the Mandellos. As a German citizen, Arno Mandello was interned as an ‘enemy alien’ after the outbreak of war in September 1939, but was able to join the Foreign Legion and spend several months in Algeria. The French armed forces refused to accept him. Mandello later portrayed the situation as if her husband had voluntarily joined the army and both had subsequently acquired French citizenship. In fact, in October 1940, the Nazi regime revoked their German citizenship, leaving them stateless.

Jeanne Mandello initially remained in Paris and, like many other women of German descent, including the philosopher Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), was interned in the French concentration camp at Gurs in southwest France in May 1940. As many of the ‘May Women,’ she was presumably liberated in June 1940 after the armistice.

Fig. 3: Johanna Mandello’s (Johanna Grünebaum’s) French identity and travel document for “refugees from Germany” (“réfugiés provenant d’Allemagne”), 1938; private collection © Isabel Mandello de Bauer.

Shortly afterward, Mandello was able, via the Red Cross, to contact her husband, who was demobilized after the Franco-German armistice, and he joined her in a village in southwest France, where the couple survived by doing odd jobs for local farmers and businessmen and sought emigration papers. They were unable to return to Paris, and in January 1942, their photo studio there was sealed, emptied, and ‘Aryanized’ by the German occupiers. Arno Mandello’s personal notes reveal how he felt during this time. He described himself as a “pariah,” an outcast who had experienced bitterness and disappointment yet still wanted to remain grateful and hopeful. In his diary, Arno Mandello, who was not religious, wrote in 1941: “I have to think of the past, of my parents’ house, of my grandfather, who had such strong faith. I, a doubter who tries to explain everything with rational arguments, a voice begins to stir within me, how difficult it is for me to hear and listen, that says, believe in the good! How happy to be able to believe.” The Memoirs of Arno Grünebaum, various dates (here May 1941), without page numbers; Isabel Mandello de Bauer private collection.

Once again, through her uncle Seligsohn, who was already living in Argentina, Mandello and her husband obtained visas to enter Uruguay. In the summer of 1941, the couple was finally able to leave France and set off for South America. Jeanne Mandello’s father would also arrive in the country somewhat later; her sister had already emigrated to Argentina via Montevideo in 1939.

Uruguay sided with the Allies from 1942 onwards, but had already welcomed European emigrants. According to estimates, between 1933 and 1945, about 7,000 to 10,000 German-speaking Jews found refuge there. Like most of them, the Mandello family settled in the capital, Montevideo, where they again worked as photographers, made a name for themselves, and became acquainted with numerous representatives of the cultural and art scene. Jeanne Mandello photographed the painter Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949), the writer Jules Supervielle (1884–1960), as well as the poets Rafael Alberti (1902–1999) and María Teresa León (1903–1988). She also documented numerous buildings by Uruguayan architects that were inspired by the modern architecture of the Bauhaus.

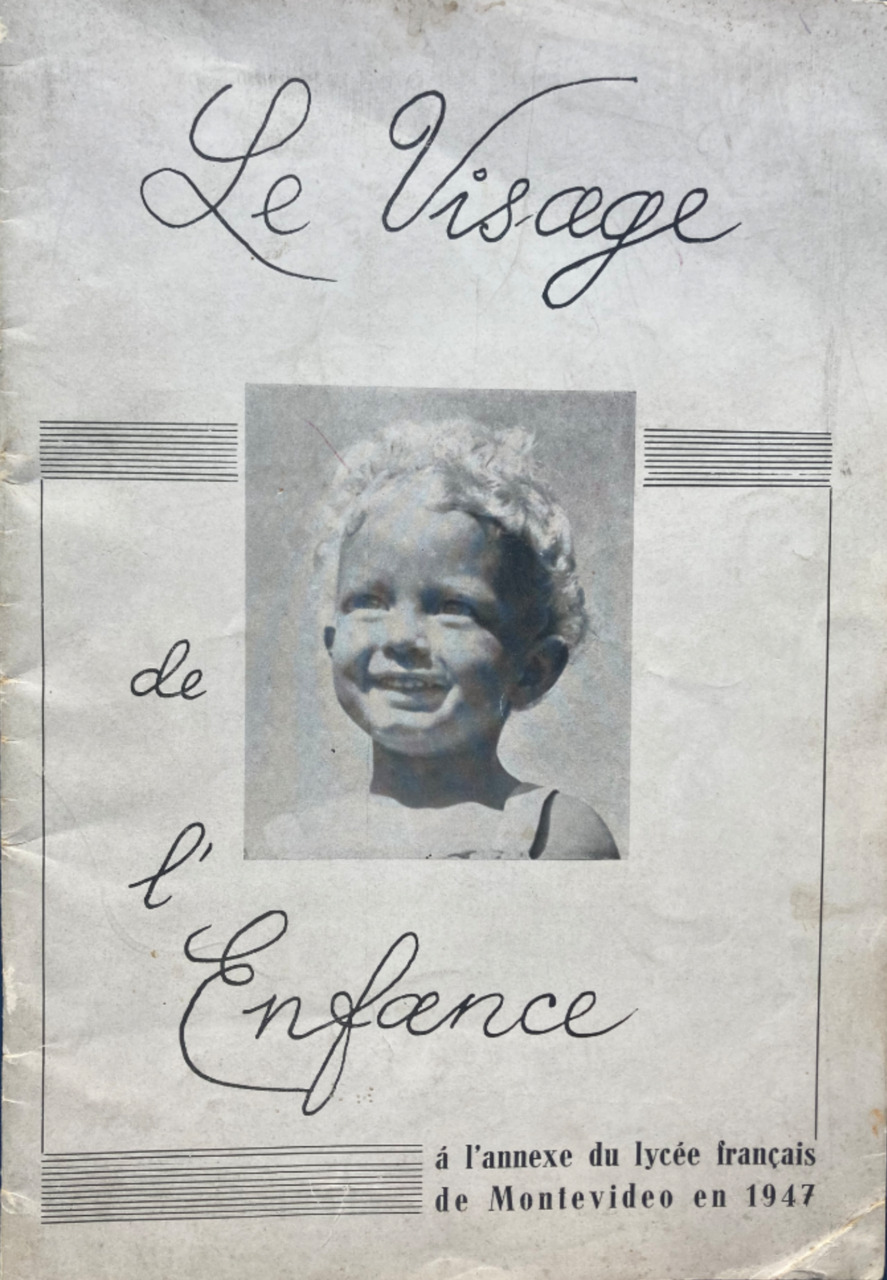

The Mandellos introduced themselves, at least publicly, as ‘French’ and sought the proximity of the French immigrants. Jeanne Mandello reported that immediately after her arrival, she wanted to teach French and worked as a photographer for the French high school in Montevideo.

Fig. 4: Brochure of the French Lycée (French high school) in Montevideo with photos by Jeanne Mandello, 1947; private collection.

At the same time, the couple established good contacts, perhaps even friendships, with other German-Jewish exiles. In his autobiography, the journalist, critic, and editor J. Hellmut Freund (1919–2004), who also found refuge in Uruguay, mentioned how he introduced the Mandellos to the respected Uruguayan art patron Susana Soca (1906–1959). According to Freund, it wasn’t difficult to bring the photographer couple, who had run their own studio in Paris, together with Soca and other prominent figures in Montevideo.

Freund provides another key to understanding why the Mandellos in Uruguay – predominantly – posed as French. In addition to Spanish actors, French actors, in particular, were welcomed and revered in Montevideo, and one can certainly draw an analogy here between actors and artists in general.

Freund, who grew up in Berlin and fled to Uruguay with his parents in 1939, was closely connected to the German-Jewish community in Montevideo. Since 1934, there had been an Aid Association for German-Speaking Jews and, starting in 1936, the German-Jewish New Israelite Congregation of Montevideo, which published a weekly community newsletter. Freund’s father, Georg Freund (1881–1971), managed it from 1941.

While Jeanne Mandello later did not speak about her (German-Jewish) affiliation, Freund described his new, hybrid identity as follows: “My existence in Montevideo was twofold: There were fellow companions in misfortune, some of them more emigrants than immigrants. We interacted with one another. […] I couldn’t shed my past, deny my origins—German, Jewish, or German-Jewish. Entering Uruguayan everyday life, communicating, and speaking the Spanish of the Río de la Plata as fluently as possible—was necessary and natural.” J. Hellmut Freund, Vor dem Zitronenbaum. Autobiografische Abschweifungen eines Zurückgekehrten,Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2005, 336.

Mandello also learned Spanish, but in everyday life, “just like that,” as she later reported, and never with perfect grammar. She seemed to have largely shed her roots. Yet there are indications of a reliance on German-Jewish contacts in Montevideo, which served as a kind of safety net but were not made public. Jeanne and Arno Mandello received Uruguayan citizenship in 1949, which they retained until the end of their lives. Unlike some other Jews in Uruguay, they did not apply for a German passport.

Fig. 5: “Two prestigious French photographers collaborate on ‘Mundo Uruguayo’” in: Uruguayan World, no. 1257, 1943, 41; private collection © Isabel Mandello de Bauer.

The Mandello couple separated in the early 1950s, but remained friends. Jeanne Mandello married Lothar Bauer (1905–1968), a Jewish journalist who had fled to Brazil and whom she knew from Frankfurt. She met him again in Rio de Janeiro in 1952 when the Mandellos had an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. When Bauer was supposed to work for the Frankfurter Zeitung in Germany at the end of the 1950s, Mandello wanted only one thing: to leave again quickly. In a 1997 interview, she recalled this time: “I was very unhappy in Frankfurt […]. It rained all the time, everything was so sad and seemed terrible to me. Sometimes I went to the botanical garden. There were greenhouses with tropical palm trees, and I sat there—at least it was warm and humid, and I liked that—and I felt good and cried.” Interview Valdivieso 1997, 18.

However, Mandello used her stay in West Germany to file a claim for compensation with the state of Hesse in 1958. Like other German Jews who had survived the Shoah, she likely applied for compensation for the destruction of her parents’ home during the war, and also for all photographic work from her German years.

In 1959, Lothar Bauer was able to transfer to Spain, where Mandello lived and worked as a photographer until her death in 2001. She re-connected with Germany and her Germanness in 1994 when the Museum Folkwang in Essen organized the groundbreaking exhibition “Fotografieren hieß teilnehmen. Fotografinnen der Weimarer Republik.” (“Photography meant participating. Women photographers of the Weimar Republic”). Mandello traveled to the exhibition and was happy to meet other photographers who had followed a similar path, including the photographer and art dealer Marianne Breslauer (1909–2001), who had emigrated to Switzerland.

Arno Mandello returned to France in 1955. Together with the English artist Helen Ashbee (1915–1996), he moved to a farm in Apulia, Italy, in the late 1960s, where he continued to work as an artist. In 1966, his photograms and collages, also called ‘Lightscapes,’ were exhibited in the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf. In contrast to Jeanne Mandello, at the end of his life, as he lay dying from a serious illness, Arno Mandello was drawn back to his Jewish roots. Friends reported that they summoned a rabbi from Rome to his bedside. Mandello had been unresponsive for days, but suddenly reacted to the rabbi’s Yiddish address. He responded, also in Yiddish, praying and singing with the scholar. A few days later, Mandello is said to have died peacefully.

Today, the artistic work of Jeanne and Arno Mandello, who were forced to juggle between countries, continents, and languages during the Nazi era because of their Jewish origins, lives on in collections and temporary exhibitions. Their multifaceted identity defies clear definition. At least in France and Uruguay, however, they also had one foot in the German-Jewish diaspora.

Website about Jeanne Mandello, Editor: Sandra Nagel: http://jeannemandello.com/

Interview with Jeanne Mandello, conducted by Susanne Knöner, for the Museum Folkwang, Essen, 1994. Photographic collection of the Museum Folkwang.

Personal collection of the Mandello de Bauer family, including personal memoirs of Arno Grünebaum (various dates, without page numbers) and identity papers of Jeanne Mandello.

Article about Jeanne Mandello, written by Marion Beckers for the Hidden Museum: https://www.dasverborgenemuseum.de/artists/mandello-jeanne-en

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Sandra Nagel is a high school teacher of German and history in Paris and a freelance curator and researcher (https://pastnotpast.com/), among others, for the Imperial War Museum, the Mémorial de la Shoah, and the French Cultural Network Abroad. Her research focuses on the Shoah in general, German-Jewish exile and internment in France, particularly in the Les Milles camp, and the rehabilitation of forgotten artists such as Jeanne Mandello. Her most recent publications are “Curatorship and Gender Exhibition Design” in Routledge Companion to Global Photographies, London 2024, and “Ilse Salberg – Creating ‘Order’ in Times of Chaos” in Enunciación Visual, Universidad de Palermo, Buenos Aires 2025.

Sandra Nagel, Jeanne and Arno Mandello (translated by James Bauer), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-7> [January 17, 2026].