Born on May 27, 1884 in Prague, Austro-Hungarian Empire (today Prague, Czech Republic)

Died on December 20, 1968 in Tel

Aviv, Israel

Occupation: Writer, critic, composer

Migration: Mandatory Palestine (later Israel), 1939

“It sometimes seemed to me, […] as if the last emanations of literary Prague were coming to life in Tel Aviv. The sun of Prague sets in the Mediterranean Sea.” „Es kam mir manchmal vor, […] als lebten letzte Ausstrahlungen des literarischen Prag in Tel Aviv auf. Die Sonne Prags geht im mittelländischen Meer unter.“ Max Brod, Der Prager Kreis, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1979, 224 (translation by the author). This sentence, taken from Max Brod’s famous work on The Prague Circle (1966), could also be seen as a (melancholy) summary of his life. A life and work that represent significant cornerstones of twentieth-century European Jewish cultural history. In addition to his contributions to literature and music, where Brod achieved great success as an author, critic, composer, and mentor, he played a role as a politician (a Zionist) and dramaturge. As a member of the German-speaking minority in Bohemia, Brod represented and helped shape the rich Jewish literary and cultural history of Prague in the early twentieth century. He was also a co-initiator of a specifically local Jewish-Zionist concept. After he fled to Tel Aviv in 1939, on the one hand, Brod was interested and willing to engage with his new environment and actively participate in the creation of an Israeli national culture; on the other hand, he remained committed to the proverbial “World of Yesterday” (Stefan Zweig), to which he dedicated numerous novels, not the least of which was his writing about Kafka. It recalled the golden age of pre-war literary ‘Habsburg’, touching on the very heart of European culture and its often German-Jewish heritage. Accordingly, Brod’s extensive correspondence reflects the (often painful) processes of negotiation and a struggle for localization and belonging.

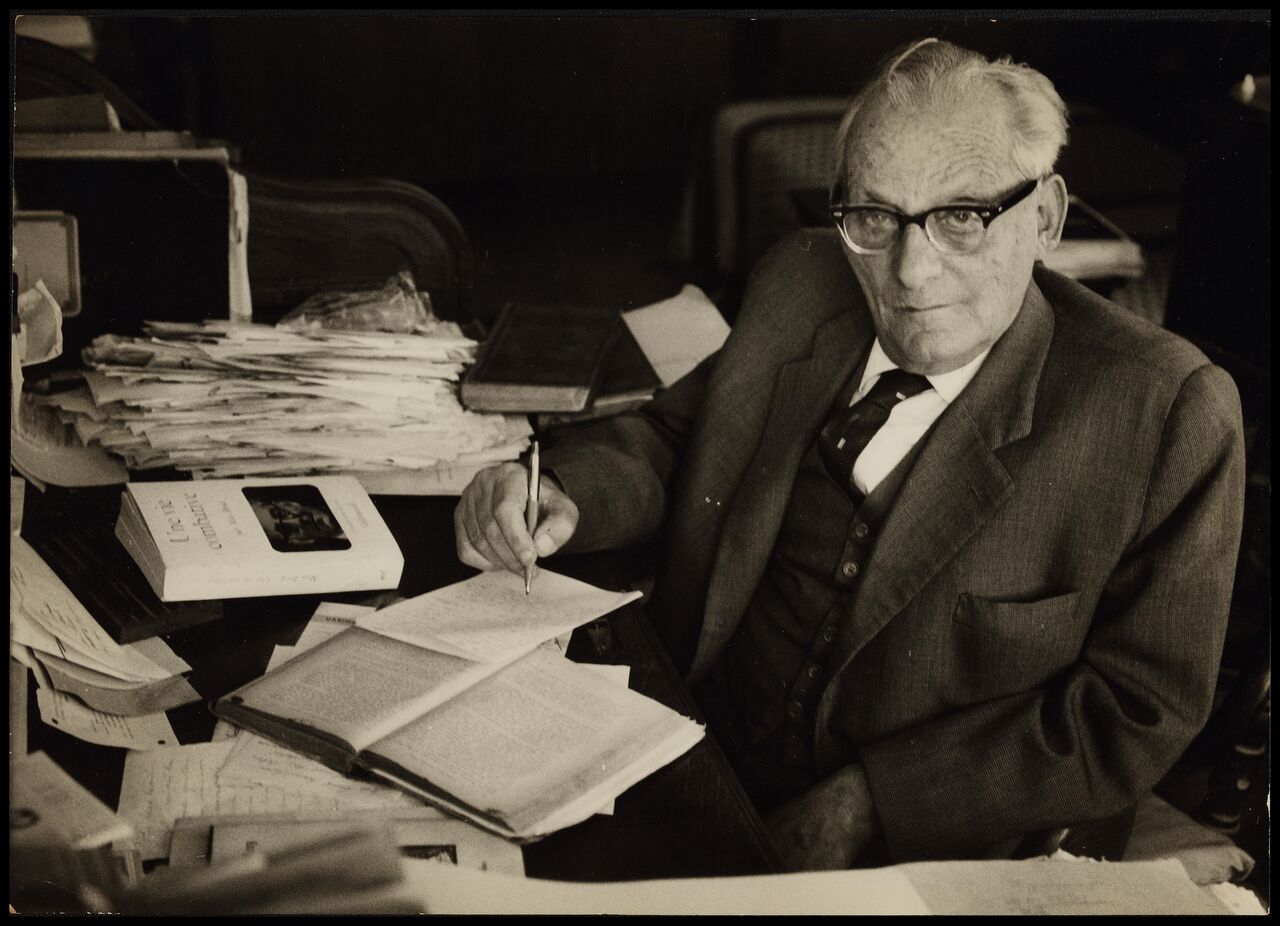

Fig. 1: Portrait of Max Brod sitting at his home desk, 1964. It was taken by the Israeli photographer Hans H. Pinn (1916–1978), who was born in Berlin; Max Brod Archive, ARC. 4* 2000 08 076, National Library of Israel.

Max Brod was the eldest of three children of Adolf (1854–1933) and Fanny/Franziska Brod née Rosenfeld (1859–1931). His family was not particularly religious, but their affiliation with Judaism was unquestioned; his father was involved in the Centralverein zur Pflege jüdischer Angelegenheiten (Central Association for the Care of Jewish Affairs), which had been founded in Prague in 1885 to safeguard Jewish civil rights in Bohemia and promote Jewish welfare. Brod attended a Catholic elementary school (Piaristenschule), where a Rabbi taught Jewish religion, and later a Gymnasium. He passed the Matura in 1902. While studying law at Charles University, Brod met the novelist and writer Franz Kafka (1883–1924), who became his closest friend. Together with the librarian and philosopher Felix Weltsch (1884–1964) and the musician Oskar Baum (1883–1941), they formed a group that Brod retrospectively called the ‘Prague Circle’ (‘Prager Kreis’). In 1913, Brod married the translator, Elsa Taussig (1883–1942), who also came from a Jewish family in Prague. The couple remained childless. Elsa Brod regularly attended meetings of the Prague Circle and assisted her husband with Kafka’s papers after he died in 1924; her list of journals is of central importance to today’s Kafka research. She also recited texts and poems (by her husband and Kafka) in public and translated works from Russian, Czech, French, and Italian.

Although Max Brod participated in the activities of the Jewish student group Bar Kochba, he had given only limited attention to Judaism in the first two and a half decades of his life, focusing instead on the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860). Against this background, he wrote his first novel in 1907, Schloss Nornepygge (Nornepygge Castle), whose protagonist embodies the indifference of this generation par excellence – and the novel was celebrated by the critics. In his autobiography, published more than fifty years after his literary debut, Brod described this novel and the philosophy behind it as a “false doctrine” (“Irrlehre”) and “wrong track” (“Irrweg” Max Brod, Streitbares Leben. Autobiographie, Munich: Herbig, 1969, 160.) that he had to live through, suffer, and overcome.

While indifference offered the possibility of analyzing – but not resolving – the great questions of belonging and meaning, the protagonist of his novel ultimately chooses suicide. It seems that it was Brod’s encounter with Zionism that gave his life a new direction – at least, that’s how he wanted his life and work to be seen in retrospect. However, this self-positioning created new problems: In his essay Der jüdische Dichter deutscher Zunge (The Jewish Poet of German Tongue), published in 1913, Brod struggled to establish himself as a German-speaking, Zionist-Jewish author. This was also a response to the philosopher Martin Buber (1878–1965), who had strongly influenced the Zionist movement in Prague with his three lectures on Judaism (1909/10) and rejected any language other than Hebrew for Jewish literature. Nevertheless, Brod, who published numerous novels and countless articles and essays in the years that followed, saw himself as a Jewish writer and was recognized as such – at least in German-speaking areas.

Fig. 2: Max Brod with his novel Reubeni, Fürst der Juden (Reubeni, Prince of the Jews), 1925. Caricature by the Czechoslovak artist and writer Adolf Hoffmeister (1902–1973), 1933; Martin and Adam Hoffmeister, Prague.

In fact, Max Brod was connected to Prague like hardly anyone else: as a gifted networker, critic, and editor, he had a profound influence on the city's cultural and intellectual life. Although he was a Habsburgian, he welcomed the founding of democratic Czechoslovakia in 1918 and remained an influential figure there, thanks to his connections and proficiency in the Czech language. A life in Eretz Israel, which often relied on improvisation, was probably the antithesis of Brod’s established bourgeois existence. Although he visited Mandatory Palestine in 1928 and was fascinated by the idea of a Jewish state, the concept of Aliyah may have seemed interesting to him only in theory. Accordingly, he did not choose Palestine but instead tried to obtain a visa for the USA. In his efforts to secure a US visa, he delayed his emigration almost too long. Brod had not grasped the scale of the Nazi threat, and the realization that he had to leave his hometown came late. Eventually, he had to give up on his hopes of emigrating to America and departed instead for Mandatory Palestine.

Brod managed to escape on the last train in the early morning of 15 March 1939, shortly before the Nazis occupied Prague. Along with Felix Weltsch and his family, Max and Elsa Brod made their way from the Black Sea port of Constanța to Athens and then to Haifa. Involuntarily, he began a second stage of his life in Tel Aviv.

Fig. 3: Max and Elsa Brod at their arrival in Mandatory Palestine, 1939; ARC. 4* 2000 08 023 Max Brod Archive, National Library of Israel.

Max Brod settled in comparatively quickly, even though his letters and diaries bear witness to the difficulties of the new beginning and a personal tragedy: his wife fell seriously ill and died in 1942. In retrospect, he wanted to see the forced change of location less as an escape than as the implementation of a Zionist “life program” Brod, Streitbares Leben, 281., an Aliyah. His reputation in the Yishuv made the arrival easier. In the spring of 1939, Brod became the repertoire advisor of the Habimah Theatre, where he was primarily responsible for the repertoire and the adaptation of the selected plays. Habimah was founded as one of the first Hebrew-language theatres in Mandatory Palestine and was officially declared Israel’s national theatre in 1958. Brod also included his dramatic works in the theatre’s repertoire, for which the theatre secured a contractual right of first access. From this position as a repertoire advisor, Brod contributed to the development of Israeli national culture. Furthermore, his books were read in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem by the German-speaking community, and some were also translated into Hebrew. Brod is one of the few writers to have successfully navigated the delicate balance between German- and Hebrew-speaking cultures.

Brod was able to (partially) reactivate his Prague network in Palestine as well, which included his old friend Hugo Bergmann (1883–1975), a professor of philosophy at the Hebrew University, and Buber. At the same time, he adapted to the new living conditions and expanded his circles accordingly. Although Brod required linguistic support, he was well-represented in the Hebrew press and had a regular column in the Hebrew trade union’s newspaper Davar. Meanwhile, a fruitful connection arose between him and the Hebrew poet Shin Shalom (1904–1990): Brod translated some of Shalom’s poems into German, and together they co-authored several literary pieces in German and Hebrew, including the libretto for the first Hebrew opera (Dan the Guard), which was premiered in 1945 with music by the Israeli composer Marc Lavry (1903–1967). In fact, music must be considered an important yet often underestimated part of Brod’s work: He was a talented pianist and composer known in Prague for his music criticism. As a result, he quickly became interested in the music of his new surroundings and published the first musical history of Israel in 1951.

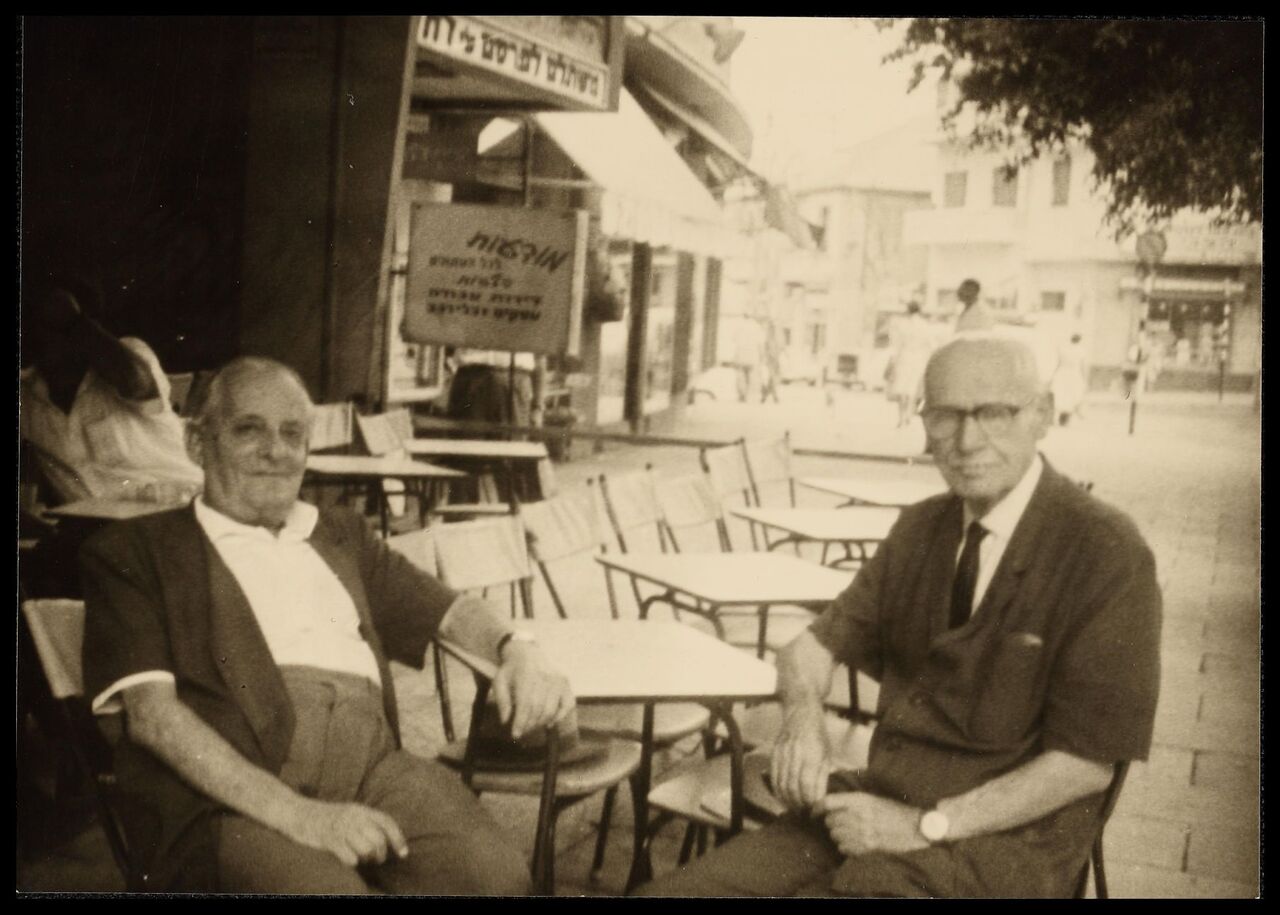

Fig. 4: Max Brod and Felix Weltsch sitting outside in a café in Israel, around 1964. The photo was taken by Ilse Ester Hoffe (1906–2007), who became Brod’s secretary and partner; Max Brod Archive, ARC. 4* 2000 08 083, National Library of Israel.

Max Brod was the administrator of Franz Kafka’s literary estate and had already devoted a great deal of attention to the remembrance of his close friend in Prague. His first biography of Kafka was published there in 1937; a second edition followed nine years later at Schocken Publishing House Ltd. in New York, founded by the German-Jewish entrepreneur Salman Schocken (1877–1959). And ‘Kafka’ fled together with Brod – even during his escape, Brod had never let the manuscripts and documents out of his sight, bringing them in a suitcase safely to Eretz Israel. From there, he continued to guide the public reception and interpretation of Kafka’s work, which had a lasting influence: in publications such as Franz Kafkas Glauben und Lehre (Franz Kafka’s Faith and Teaching, 1948) or Franz Kafka als wegweisende Gestalt (Franz Kafka as a Pioneering Figure, 1951), he shifted his (post-Shoah) image of Kafka from a Jewish writer to a prophetic-messianic figure. Brod’s motivation for appropriating and marketing Kafka’s lifework, as if acting as his literary agent, is complex. Economic considerations certainly played a role, but control over how Kafka’s work was interpreted was also linked to broader efforts to establish a culture of remembrance – one centered on the lost world of Prague’s German-speaking Jewish minority.

Despite all his efforts to master the Hebrew language, Max Brod primarily remained rooted in the German-speaking culture. The complicated process of learning Hebrew is frequently addressed, particularly in his letters to Weltsch in Jerusalem. Although he was able to speak and read Hebrew, Brod did not become a Hebrew writer and, therefore, did not make the leap into the ‘new Israel’ – likely due in part to his age. He remained dependent on the German-speaking publication area, traveling to Switzerland, West Germany, and Austria every year, where he completed a packed program of lectures, interviews, and business meetings. Brod was certainly aware that a large part of his former readers had been murdered, some of them by those who had invited him since the 1950s. Meanwhile, his circle of friends and network in Israel increasingly consisted of German-speaking immigrants known as Yekkes. This did not mean that Brod rejected his surroundings or wished for a different place of residence; rather, he sought to establish a relationship between Prague and Tel Aviv or to maintain Prague within Israel.

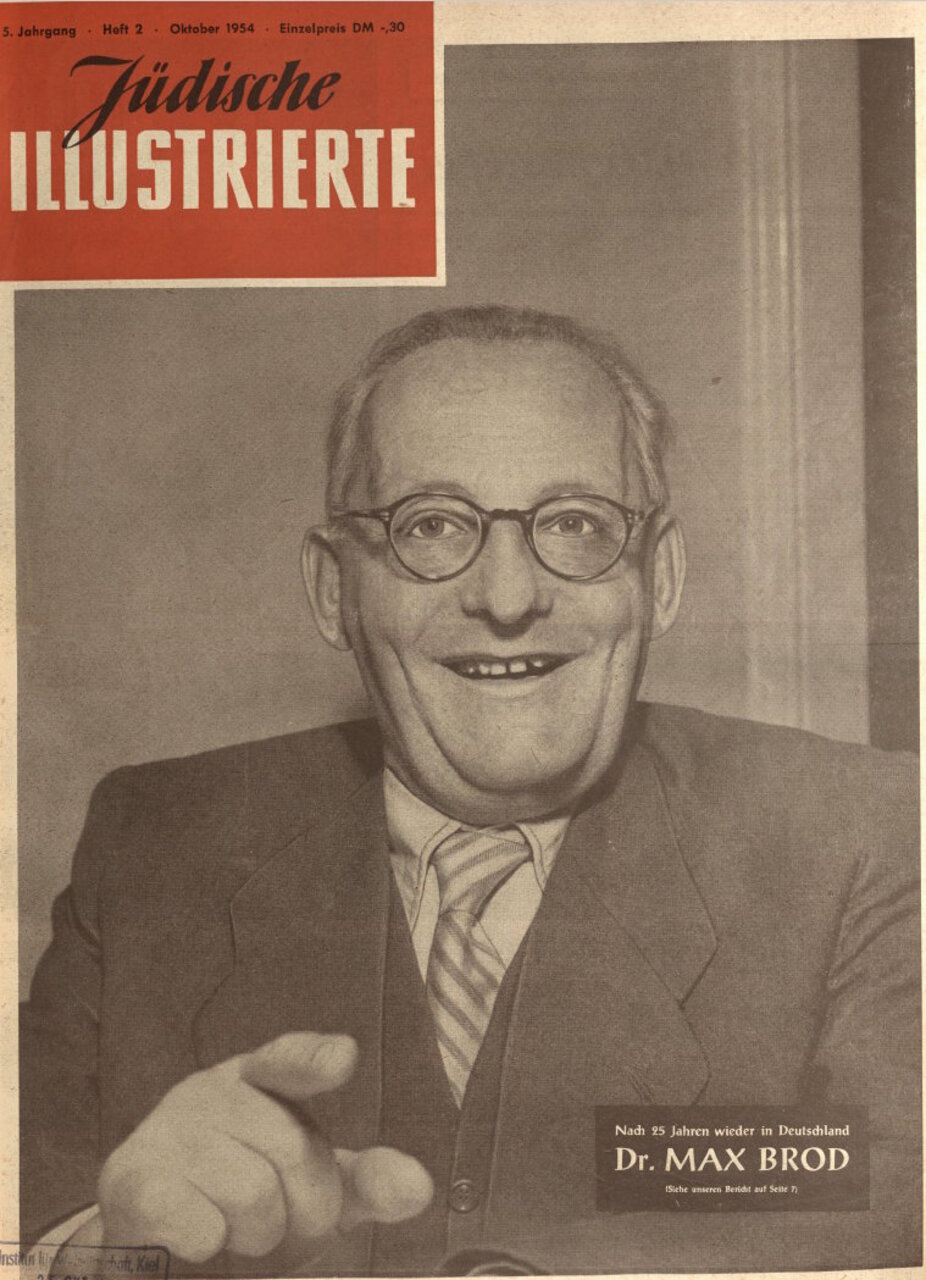

Fig. 5: “Nach 25 Jahren wieder in Deutschland. Dr. Max Brod“ (“Back in Germany after twenty-five years. Dr. Max Brod“), the cover of the Jüdische Illustrierte, supplement to the Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland, 1954.

With the so-called Prague Circle, Brod has created a literary place of remembrance that has endured to this day. A melancholy passage from this book, The Prague Circle (1966), published two years after the death of his long-time friend and companion, Felix Weltsch, is emblematic of this. In it, Brod described the meetings of the ‘Taussig Circle’ which was founded in 1941 by his brother-in-law, Ernst Taussig (1888–1949), and his wife Nadja Taussig née Schnitkind (1905–1998). The couple brought together several Yekkes interested in literature and music; regulars included rabbi Schalom Ben-Chorin (1913–1999) and the writer Sammy Gronemann (1875–1952). For Brod, these gatherings of German-speaking Jews connected the past with the present, Prague with Tel Aviv, ‘Habsburg’ with Israel. Max Brod died in December 1968 at the age of 84.

Kafka (1): Max (ARD miniseries 2024): www.ardmediathek.de/video/kafka/max-s01-e01/ndr/Y3JpZDovL25kci5kZS80OTg3XzIwMjQtMDMtMjYtMjAtMTU (available in Germany until November 11, 2026)

“Max Brod im Gespräch”, in: ARD Retro 1968: www.youtube.com/watch?v=HLLoWh45jOA

Digital edition of Max Brod’s diaries (in progress), Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach: www.dla-marbach.de/forschung/editionen-und-digital-humanities/digitale-edition-tagebuecher-max-brod/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

PD Dr. Anna-Dorothea Ludewig (https://www.mmz-potsdam.de/en/team/anna-dorothea-ludewig) is a literary scholar and researcher at the Moses Mendelssohn Center for European-Jewish Studies in Potsdam and a lecturer at the University of Potsdam (“Privatdozentin”). Currently, she is the co-head (PI) of a DFG project on Jewish film heritage and is working on a biographical project on Max Brod’s years in Palestine/Israel.

Anna-Dorothea Ludewig has recently published an edition of the correspondence between Rainer Maria Rilke and Ilse Blumenthal-Weiss (with Torsten Hoffmann, Wallstein, 2024) and was the guest editor of the Yearbook for European-Jewish Literature Studies 2025 (with Ulrike Schneider).

Anna-Dorothea Ludewig, Max Brod (1884–1968), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-28> [February 20, 2026].