AJR Journal, the journal of the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR), is the best and richest source of post-1945 information about the community of Jewish refugees from Nazism who fled to Britain after 1933. It commenced publication in January 1946 as AJR Information and has appeared every month since. In 2000, it was renamed AJR Journal. The AJR was founded in London in 1941 to represent the Jewish refugees from the German-speaking lands, over 70,000 of whom had fled to Britain after 1933. Its journal was intended to function as a means of contact with its membership, to provide essential information to the community it represented and to act as a forum for debate on issues of interest and concern to its readers. It aimed to preserve the cultural heritage of German-speaking Jewry in the refugees’ new homeland; but it also sought to ease the process of the integration of refugees into British society, though without abandoning the German-Jewish identity that the refugees had brought with them.

The issue of May 1960 can serve as an example of the journal’s methods and achievements. It begins with an impassioned leading article by the German-born historian and sociologist Eva G. Reichmann (1897–1998), formerly one of the leading ideologists of the Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens (CV) and subsequently director of research at the Wiener Library in London. It launches into an analysis of recent German history, from the First World War to Nazism and its continuing malign legacy of antisemitism in the Federal Republic.

Reichmann’s article is followed by a page each on events in Britain, Germany and Austria and in the wider world (pages 3-5). The wide range of articles on matters of historical and cultural interest to the German-speaking Jewish refugees is evident from pages 6, 8, 10 and 15. Page 7 is devoted to the important question of restitution, while page 9 contains ‘Anglo-Judaica’, the regular column on news about British Jewry. Pages 11 and 12 demonstrate the journal’s determination to celebrate the notable achievements of German-speaking Jews, especially in the cultural field; the column ‘Old Acquaintances’ on page 11 draws on the prodigiously detailed knowledge of the writer and journalist Paul Marcus (1901–1972, PEM), who had fled Nazi Germany in 1933. Pages 13 and 14 provide readers with organisational information about the AJR and its activities, while advertisements predominate on pages 15 and 16.

AJR Information commenced publication in 1946 at eight pages in length, expanding by stages to its current length of twenty pages. The early issues of the journal were dominated by the aftermath of the Holocaust, with reports on the surviving Jewish communities in Europe and attempts to bring Nazi criminals to justice. Furthermore, it included items on the provision of relief to the Jews of Europe, where the AJR played a key role, whose location in Britain made it the bridgehead between the Jews overseas and those on the Continent. It also reported on developments in Britain affecting the refugees, such as parliamentary statements on naturalisation, which would see tens of thousands of refugees acquire British citizenship in the late 1940s.

The journal also functioned as a means by which the AJR could inform its members about its planned activities, such as meetings in towns and cities around the country, thereby acting as a link that held the newly established community, still emerging from the stresses of war, together. The sample issue of May 1960, for example, gives information on page 13 about the AJR’s annual general meeting, held that month, and about a bazaar at one of the homes for the elderly run jointly by the AJR and the Central British Fund for World Jewry.

As its title suggests, AJR Information was originally conceived as a newssheet, a more modest publication than Aufbau, its sister publication in the USA. However, AJR Information soon began to publish articles about cultural matters, with numerous highly qualified contributors writing well-informed and perceptive pieces about figures from the world of German-Jewish culture, including Reichmann. Her leading article in the sample issue of May 1960 is representative of this. Written in the shadow of the epidemic of antisemitic graffiti in West Germany (and, unusually, in German), it starts with a statement of the author’s own situation as a German Jew in Britain. Reichmann described the development of a refugee identity composed of German, Jewish and British component parts, reflecting much of the historical development of the community. For her, “what were formerly parts of a whole still feel related to one another, even after their undesired separation: that the Jewish part is most strongly conscious of itself in its sense of belonging to German-Jewish history, the formerly German part in its coming to terms with its guilt-laden relationship to its Jewish fellow human beings, and that both have gained a new dimension through their contact with the English world.” Translation by the author.

The journal also added a letters page, which became one of its liveliest and most eagerly read sections. It began to print commercial advertisements for shops and business enterprises and small ads for accommodation and employment; these are of the greatest value to any later researcher studying the social history of the refugee community. The issue of May 1960 carries a large number of advertisements, both commercial and classified, mainly on pages 13-16, as well as ads elsewhere by prominent refugee businesses like Corsets Silhouette, Ackermans Chocolates and the bookshop Libris.

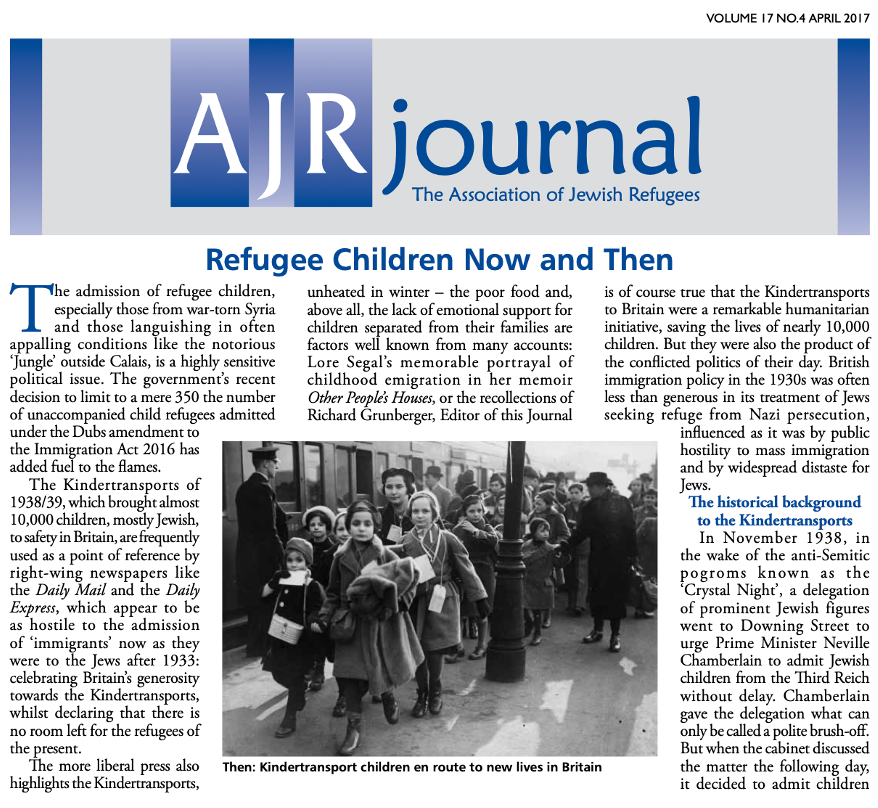

Fig. 1: The cover of AJR Information, Volume 17, No. 4 (April 2017) showing Kindertransportees en route to their new lives, circa 1938–1939. The so-called Kindertransport brought about 10,000 Jewish children to safety in Great Britain; Association of Jewish Refugees.

The AJR had come into being specifically to provide an organisational forum for those refugees conscious of their Jewish origin; given that they had been subject to Nazi persecution for precisely that reason, that was the great majority of them, even those who before 1933 had led secularised lives with little engagement with Judaism. The AJR had been founded over against the Free German League of Culture in Great Britain, which was established in 1939 by German Communists and sought to persuade the refugees to return to Germany once the war was over. But the AJR appealed to the mass of Jewish refugees who had no desire to return to their native land after the Holocaust and intended to build new lives in Britain. Consequently, AJR Information devoted considerable space to Jewish matters: to religious figures such as Rabbi Dr Leo Baeck (1873–1956) or to relations with Anglo-Jewry, by means of a dedicated column, ‘Anglo-Judaica’, which, as shown on page 9 of the issue of May 1960, aimed to inform readers about events in the wider world of Anglo-Jewry, such as Jewish Book Week or the annual general meeting of the Council of Christians and Jews. Furthermore, to the religious institutions founded by the refugees, especially the New Liberal Jewish Congregation (now Belsize Square Synagogue), later established in its own building in Belsize Park, north-west London; and not least by plentiful articles on developments in Israel, supportive but not uncritical of the new state.

The AJR sought in many respects to carry on the heritage of the representative organisation of the Jews of Germany before 1933, the Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens; significantly, a number of its most prominent members had been active in the CV before emigration, among them Reichmann.

On the model of the CV, the AJR was particularly active in the field of social care. The AJR employed its first social worker, Dr Adelheid Levy (1897–1979), very soon after its foundation. She served as head of the AJR’s Social Services Department from its inception in 1941 until 1968. AJR Information carried regular reports on the Social Services Department; it subsequently set up a network of such institutions, including an employment agency and an AJR Club to provide social contact for elderly and lonely refugees, which were allocated considerable space in the columns of AJR Information.

The most significant development in this area was the AJR’s participation in the management of old age homes for elderly and infirm refugees, funded from the proceeds of the sale of heirless, unclaimed and communal Jewish property in Germany. News about events in these homes was a staple in the journal.

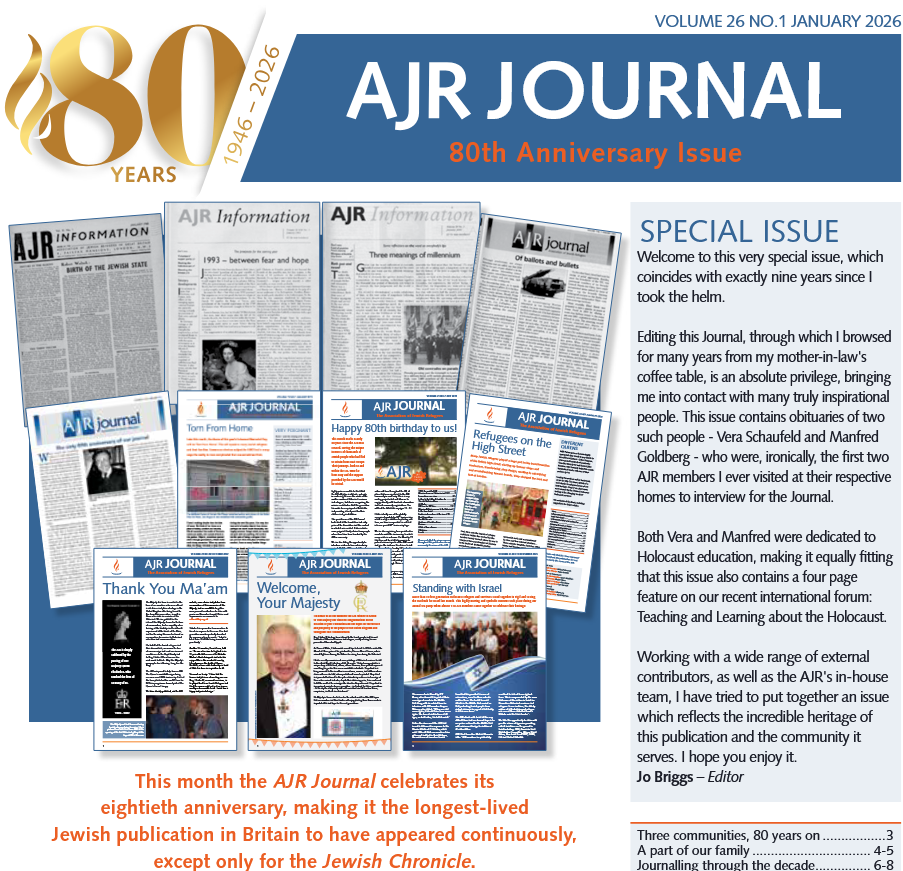

The salient feature in the history of the AJR Journal and of the AJR itself has arguably been its sheer longevity: the journal can claim to be the longest continuously appearing Jewish publication in Britain after the Jewish Chronicle, whereas Aufbau, its celebrated sister journal in the USA, ceased publication there in 2004.

This shows that the community of the Jewish refugees from the German-speaking lands has preserved its particular identity down the decades, unlike its sister communities around the world; the communities in Israel and the USA have largely been absorbed into the great Jewish communities around them, while those in continental Europe were destroyed in the Holocaust. In Britain, however, where the existing Jewish community was smaller and less dynamic than that in the USA, and where conditions were favourable for the flourishing of a communal organisation of the German-speaking Jews, the AJR has represented in turn the generation of the refugees themselves, the second, third, and even the fourth generations. This generational shift was also displayed in AJR Information. Its long-term founding editor, Werner Rosenstock (1946–82), was a first-generation refugee.

Fig. 2: The eightieth anniversary issue of AJR Journal, Volume 26, No. 1 (January 2026); Association of Jewish Refugees.

One reason why the community of Jewish refugees from Germany has maintained its separate identity is that relations between that group of refugees and Anglo-Jewry, largely the descendants of an earlier wave of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, have remained somewhat distant. While Anglo-Jewry was generous in its material support for the refugees in the 1930s, the social and cultural differences between the assimilated, secularised Jews of the German cities, with their attachment to German-language Bildung, and the Jews from Eastern Europe, more attached to traditional customs and practices, more religiously observant, and Yiddish-speaking, were to a considerable extent replicated in Britain.

The Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe had largely arrived poor and ill-educated and had settled in working-class districts like the East End of London; the refugees from Nazism, by contrast, were mostly middle-class, well-educated, eager to integrate at the equivalent level in Britain, and settled in solidly middle-class areas like Hampstead. To these social aspirations, which aroused a certain resentment among some British Jews, were added the cultural and intellectual aspirations of the refugees from Germany; whereas the social culture of Anglo-Jewry had largely developed from that of the communities of Eastern Europe, that of the later wave of refugees had drawn on the veneration for education and high culture that had characterised German Jewry. Unaccompanied refugee children, for example, often found that their aspiration for a university education, inspired by their parents, was greeted with incomprehension by their British Jewish foster parents, or was refused by the Anglo-Jewish organisation responsible for their care, which instead pointed them towards agricultural training for emigration to Palestine.

The sample issue of May 1960 contains numerous items of historical and cultural interest to its readers, on subjects ranging from the nineteenth-century historian of Jewry, Heinrich Graetz (1817–1891), to contemporary literature and academic publications of the Leo Baeck Institute.

AJR Information took a largely positive view of Britain as a place of permanent settlement for German-speaking Jewish refugees, despite the instances of hostility and discrimination that they experienced, most notably the mass internment of thousands of ‘enemy aliens’ in summer 1940. The journal regularly published articles illustrating the successful integration of the refugees into British society and highlighting the contribution that individual refugees had made to their adopted homeland. A striking example of this was the Thank-You Britain Fund, established in 1963 and administered by the AJR, for which refugees were encouraged to make donations towards a gesture of thanks to Britain. The journal’s determination to celebrate the notable achievements of the German-speaking Jewish refugees, especially in the cultural field, is evident from pages 11 and 12, with an article on the German journalist and writer Kurt Tucholsky (1890–1935) and references to other German-speaking artists. As a result of this attitude to Britain, the journal has come under attack from academics who take a more critical view of British behaviour towards the refugees from Nazism. It is nevertheless clear from the evidence, spoken and written, provided by the refugees themselves that the majority regarded Britain predominantly with affection, felt a measure of gratitude for the refuge granted them there, and regarded the process of their settlement, for all the traumas consequent on forced emigration, as broadly successful.

The journal of the AJR was written by refugees, for refugees, about what refugees were interested in or needed to know about. Almost all histories of German-speaking Jews in Britain rely primarily on government and other official records, but once the majority of the refugees had acquired British citizenship, by 1950, they ceased to be identified officially as a discrete group of non-British ‘aliens’ and fell out of such records. For that reason, the journal and other material from AJR sources take the history of this group on into the post-war decades. AJR Journal has become one of the longest continuously appearing Jewish publications in Britain, reflecting its German-Jewish diaspora until this day.

AJR Journal, Association of Jewish Refugees: AJR – AJR Journal (Online access to digital archive of issues from 1946)

Association of Jewish Refugees, Refugee Voices Testimony Archive: AJR – Refugee Voices Testimony Archive

Association of Jewish Refugees, My Story: 75 Years of the AJR: AJR My Story

Association of Jewish Refugees, AJR Plaque Scheme: Plaque Scheme - AJR

Association of Jewish Refugees, Britain’s New Citizens: The Story of the Refugees from Germany and Austria, Tenth Anniversary Publication of the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain, London 1951.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Anthony Grenville, son of Jewish refugees who fled from Vienna to London in 1938, was educated at the University of Oxford and lectured in German at the Universities of Reading, Bristol and Westminster. He worked with the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) and was Editor of its monthly journal from 2006 to 2017. Grenville co-founded its Refugee Voices archive of filmed interviews and co-created the exhibition Continental Britons: Jewish Refugees from Nazi Persecution to mark AJR’s sixtieth anniversary. For several years, he was a member of the executive committee of the Gesellschaft für Exilforschung and was awarded Ehrenmitgliedschaft in 2021. Grenville was a founder of the Research Centre for German & Austrian Exile Studies, University of London, and since 2013 has served as its Chair.

Anthony Grenville, AJR Journal: The Monthly Journal of the Association of Jewish Refugees, London, in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-19> [February 10, 2026].