Palestine/Israel became one of the most important centers of the German-speaking Jewish diaspora in the 1930s. After the United States, the small country took in the largest number of German-speaking Jews. Per capita, no other country received as many immigrants from the German-speaking regions between 1933 and 1945. In total, it became the refuge for around 90,000 men, women, and children – 60,000 from Germany and 30,000 from Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and the Free City of Danzig.

They arrived in a foreign land. Yet at the same time, they were moving to Eretz Israel, the Land of Israel, which is regarded as the historical homeland of the Jewish people. Thus, from a Zionist perspective, their arrival was an act of homecoming. Zionism, an emancipatory nationalist movement established in 1897, sought to enable Jews to return to their “old-new” homeland after centuries of oppression and persecution. Eretz Israel was thus fundamentally different from immigrants’ other destinations, and Zionists in Palestine were offended if it was treated as part of the diaspora or even as a place of exile.

To this day, Israel is the only example of a part of a diaspora establishing a nation-state. Even so, it was often experienced as an exile at first. The hardships on the ground and the loss of the immigrants’ previous lives – which even most Zionists would not have voluntarily traded for Eretz Israel – often prompted feelings of alienation and difference.

When most German-speaking Jews arrived there, Palestine was not a sovereign state. Beginning in 1922, it was administered by the British Empire as a League of Nations mandate; before that, it had been part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuries. Whereas the State of Israel was established in 1948, a generally recognized Palestinian state does not exist to this day.

Under Ottoman rule, only a few dozen German-speaking Zionists came to the country, establishing small communities in the cities. Among this group was Dr. Elias Auerbach (1882–1971), who opened the first Jewish hospital in Haifa in 1911. These self-proclaimed pioneers, such as Auerbach, often immigrated with their Zionist partners and usually lived in Palestine only temporarily. The First World War and local hardships prompted many conscription-age men from Central Europe to leave the country.

Before 1933, only about 2,000 German Zionists settled permanently in Palestine. The pre-1938 numbers from Austria were only slightly higher. For most of them, the prospect of living in Eretz Israel was no more than a declared intention, which they only began to carry out after the Nazi takeover made further postponement impossible. Most German-speaking Jews who immigrated from 1933 onward – especially from Germany, and after 1938 increasingly from Austria and Czechoslovakia – were not Zionists. Zionists had been a small group in the German-speaking region of Europe. Those who came to Palestine after 1933 or 1938, respectively, usually did so because more desirable Western countries such as United States were out of reach. This was particularly true for people from Austria. Overall, obtaining admission to Palestine was somewhat easier, even though the British Mandatory government never welcomed mass Jewish immigration and indeed introduced quotas capping the number of immigrants.

Any prospective immigrant to Palestine – Jewish or non-Jewish – required a certificate. These certificates – tsertifikatim in Hebrew – were divided into four categories: Category A was for individuals with enough money to support themselves. Category B included those whose support was secured by a public institution in Palestine. C certificates were for people between 18 and 35 years old with prospects of employment. D certificates were for those who had relatives in Palestine.

The majority of German Jews immigrated under A certificates. While the gender ratio of immigrants was almost at parity overall, women accounted for only about a third of the C certificates, and B certificates were more frequently granted to male applicants. Unlike Jewish immigrants to the US or UK, slightly more men than women therefore came to Palestine. This development was not solely due to the Mandatory government, which regulated categories A, B, and D. Category C certificates were awarded by the Yishuv, the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine represented by the Jewish Agency. The Yishuv was also particularly interested in bringing in able-bodied men to support and defend the Zionist development project.

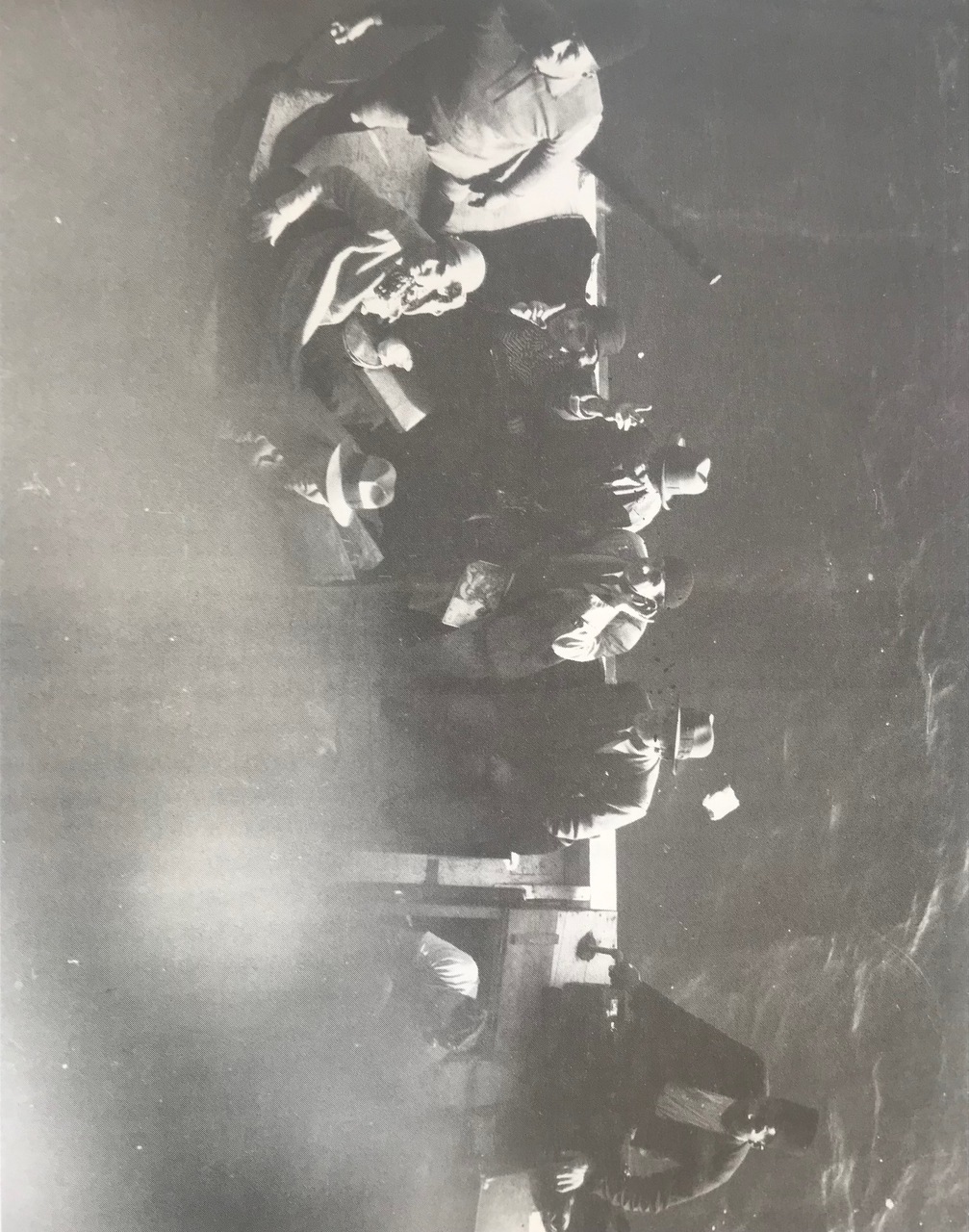

On the whole, the immigration of German-speaking Jews in the 1930s was largely a family affair, with most arriving together with their parents, spouses, and children. In many cases, the men traveled ahead to Palestine on exploratory visits. They almost always arrived by sea, some via Egypt or Lebanon. The ports of Trieste and Marseille, as well as Genoa and Bari, served as central departure points from Europe. The day of arrival in Palestine often left a strong impression, and for some, it was a shock. Many recalled the experience of disembarking in the old port city of Jaffa, where ships anchored offshore due to the rocky waters and passengers were ferried ashore on small wooden boats, as an unreasonable ordeal.

Fig. 1: Arrival of German Jews in the old port city of Jaffa – with talking hands, around 1933.

Zionists call Jewish immigration to Eretz Israel an Aliyah, or ascent, even though at the time it almost always meant a drop in a person’s socioeconomic status. Palestine was an agrarian country in an economically weak region, which many in Central Europe viewed as backward. The British Mandatory government was therefore keen for the immigrants to contribute to the country’s economic progress. The Fifth Aliyah, the wave of immigration between 1929 and 1939, included a large share of German speakers and was thus also known as the “German Aliyah” even though an even larger number of Jews came from Poland during this period. This wave consisted mainly of middle-class individuals who, in the early 1930s, brought capital into the country. The Ha’avara Agreement played a central role in this flow, encouraging many German Jews to choose Palestine as their destination. (It did not apply to immigrants from Austria or Czechoslovakia.) From 1933 to 1939, the agreement allowed the Nazi regime to promote the export of German goods to Palestine while permitting Jews to transfer some of their assets there, subject to a reduced Reich Flight Tax. The systematic extortion and confiscation of Jewish property later led to an increasing number of impoverished people arriving in the country. This particularly affected Jews from Austria, who, after 1938, were often forced to flee with little or no possessions. The timing of immigration thus had a significant impact on a person’s initial social standing.

German Jews in Palestine were given their own label: Yekkes. The etymology of this term, which was used both humorously and derisively, remains unclear. It may have referred to the jackets (in German, Jacke) that many Yekkes continued to wear even in the heat, or to a Hebrew acronym describing a Jew who is slow to grasp things. As late as 1979, a German Jew filed a lawsuit with the Supreme Court in Jerusalem because he considered the term insulting. The label was often applied to German-speaking immigrants from other countries as well.

Many Jews from Berlin, Prague, or Vienna – even though they did not develop a cohesive diasporic culture – shared the same general socio-cultural background as well as a common language. Most were middle class, secular, acculturated to their societies of origin, and they often placed great value on education. These attributes are reflected in the stereotypes of Yekkes as suit-wearing intellectuals with university degrees or as consumerist “Kurfürstendamm Ladies,” a reference to a well-known shopping boulevard in Berlin. Of course, the group also encompassed other lifestyles, such as those of large Orthodox families from Burgenland or Württemberg.

In Palestine, this group of immigrants faced a completely different life: professors climbed on scaffolding, opera singers sold sausages, and lawyers whitewashed chicken coops. Many men could not continue working in their previous professions, either because their skills were not needed or because they required retraining, as in the case of lawyers. For women, many of whom had not previously been employed outside the home, daily life changed fundamentally. They often became the primary breadwinners, as they were more willing to take on poorly paid jobs. They supported their families as service workers, such as nannies or cleaners. They were also expected to perform domestic tasks that had often been handled by domestic workers in their former lives. This dual burden was exhausting. Meanwhile, men often suffered from depression, their traditional gender roles as heads of household having become precarious.

The situation was also difficult for children, even though they generally adapted more quickly. They often had to help their parents and give up on the prospect of further education. Their schooling had been violently interrupted in Europe, which had long ripple effects on many of their lives.

Most German-speaking Jews gravitated towards one of the country’s three main cities: Tel Aviv, where they preferred living in the north around Ben-Yehuda Street; Jerusalem, where they dominated the middle-class neighborhood of Rehavia; and Haifa, where they mostly settled in leafy Hadar HaCarmel. Haifa, in particular, developed into a partly “Yekke” city. By 1938 more than 20 percent of its Jewish population had origins in Central Europe. Those who could afford it brought their belongings in shipping containers – known as “lifts” – including pieces of Wilhelmine-era furniture, mementos of their middle-class lifestyles in the Old Country.

Fig. 2: Lift belonging to the Klein family from Vienna, which was converted into a chicken coop. The family came from a wealthy background and found refuge in Haifa, where they initially had to live in modest circumstances on the outskirts of the city, 1942; Dr. Jakob Eisler, Stuttgart.

About a third of them settled in rural areas. Agricultural settlements founded by German-speaking immigrants included the kibbutz HaZorea in northern Israel, Ramot HaShavim, Sha’ar Hefer, Shavei Tzion, and Nahariya – now a city of more than 60,000 inhabitants. These settlements were largely shaped by their settlers’ shared region of origin. For example, Shavei Tzion with its Rexingen-born residents was also known as the “Swabian settlement,” while the founding generation of Sha’ar Hefer was predominantly Czech.

Mittelstandssiedlungen (middle-class settlements) were a typical settlement pattern for German-speaking Jews in Palestine, enabling rural life even for residents with no agricultural training. Life there was particularly challenging. Often, an initial shelter was cobbled together from a “lift” and people showered outdoors. Meanwhile, the cities suffered from a severe housing shortage, and several families often shared an apartment. Thus, settling the countryside was not only a goal of the Zionist development ideology, but a practical necessity. In particular, young people who had been trained at Hakhshara centers in Europe were deliberately sent to rural areas.

In the larger cities, cafés, delicatessens, pastry shops, ice cream parlors, and restaurants were opened, offering Old Country specialties such as apple strudel, pretzels, and Wiener or Frankfurter sausages. For German-speaking Jews, the local cuisine – including vegetables most of them had never seen, such as zucchinis and eggplants – took some getting used to. They longed for familiar foods, which inspired some families to open lunch counters. Additionally, there were antiquarian bookstores, bookshops, guesthouses, theaters, cinemas, and specialty shops such as record stores that catered to German-speaking customers. These created islands of familiarity in what was initially a foreign country, where the new climate made an afternoon nap a crucial necessity. Instead of the old summer thunderstorms, there were cloudless skies with 35-degree heat and seasonal desert winds; instead of leafy, deciduous trees, there were olive trees and newly introduced eucalyptus trees, which had been planted in the nineteenth century to drain swamps and combat the dreaded, infectious malaria.

Fig. 3: The Krips pastry shop in Haifa, founded by Walter Krips (1911–1992) from Frankfurt, pictured here standing at the front, 1947. The logo of the café, which was particularly popular among Yekkes and existed until the 2000s, was a pretzel; private archive Sonja Mühlberger, Berlin.

In response to these new realities, the German Zionists who were more established in Palestine set up a mutual aid organization to support the newcomers, especially during the difficult early days. In 1932, they founded the Hitahdut Oley Germania (Association of Immigrants from Germany, HOG), which helped arrange housing and jobs, offered language courses and retraining programs, and established a support network for those in need that exists to this day. Austrian Jews had initiated their own association (Hitahdut Oley Austria, HOA), which merged with HOG in 1938 to form the Hitahdut Oley Germania ve Oley Austria (HOGOA). A minority within HOA opposed this merger, demonstrating that the development of a common “Yekke” identity was not universally accepted. In 1942, HOGOA was eventually renamed Irgun Oley Merkaz Europa (IOME), the Association of Immigrants from Central Europe, which also included members from Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary.

Beginning in 1932, the association published its own magazine, the Mitteilungsblatt, which was initially an informational leaflet that was not for sale at any newsstand. German-language publications faced considerable resistance in the Yishuv, especially during the Second World War. The IOME’s focus on immigrants’ country of origin was also a thorn in the side of the Yishuvniks, as some of the established Eastern European Jews in Palestine were known. The Yishuvniks had immigrated from 1882 onwards, fleeing pogroms and poverty, and had never established a comparable mutual aid organization. They advocated the idea of a “melting pot,” according to which any diasporic identity – especially hyphenated ones, such as German-Jewish – should be melted down to form a new Zionist identity. The Hebraization of German names attests to this. For example, Felix Rosenblüth (1887–1978), Israel’s first Minister of Justice and a founding member of HOG, later adopted the name Pinhas Rosen.

For Jews from Germany, who had been far more integrated into the mainstream culture of their birthplaces than the Yishuvniks had, the melting pot doctrine was a tough pill to swallow. Many had believed in a German-Jewish symbiosis. After 1933, they were no longer considered Germans in Germany, but in the Yishuv, they were often viewed as nothing but Germans. These externally imposed labels, which called their own German or Jewish identities into question, were extremely painful. They led to ambivalence about where they belonged and partly explain Yekkes’ pendulum swing towards a particularly robust pattern of independent community institutions. At the same time, the IOME emphasized that it was not a central association of German Jews, but rather a bridge to integration into Israeli society. This was finally reflected in a further renaming of the association in 2003, now known as the Irgun Yotzei Merkaz Europa (IYME), the Association of Israelis of Central European Origin.

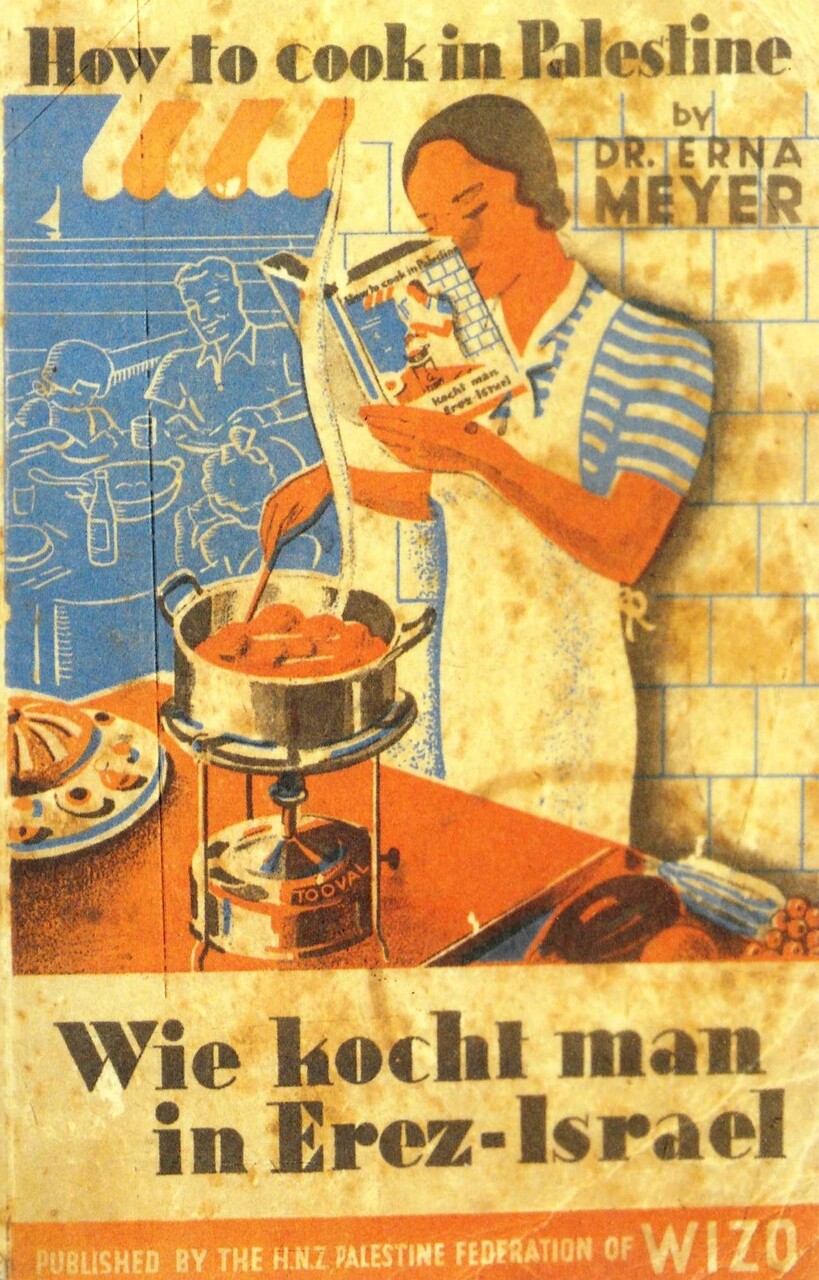

Fig. 4: Cookbook by the Berlin-born economist Erna Meyer (1890– 1975), which was reprinted several times after 1936. Meyer recommended the use of local vegetables along with local herbs and spices.

The German language was what united the diverse group of German-speaking Jews. It had been considered the focal point of a shared cultural sphere and often served as a marker of middle-class identity. In the Yishuv, however, it lost this status, even as a few German words, such as Isolierband (electrical tape), Spachtel (spatula), and Wärmflasche (hot water bottle), entered the Hebrew language. German remained frowned upon and associated with the Nazis, while Modern Hebrew (Ivrit) was to be spoken by all Jews universally. This Zionist language doctrine, which also targeted other languages, posed a significant challenge. Although German is a sibling of Yiddish, the mother tongue of most Eastern European Jews, it has no linguistic connection to Ivrit. As a result, the practice of “spoken newspapers,” in which an “editor” read aloud from the press every week, was particularly popular among the Yekkes. Only a few had arrived in the country with a solid background in Hebrew, whether from language courses or religious education. The residents’ jokey nickname for a heavily Yekke neighborhood in northern Tel Aviv – Kanton Ivrit, a pun on a German phrase roughly meaning “no Hebrew heard” – is a testament to this.

While learning Hebrew was generally easier for the younger generation, who transitioned into a Hebrew educational system, the older generation often struggled. The younger generation sometimes felt embarrassed of their parents speaking German in public, and some children reportedly crossed the street to avoid being associated with it. As a result of these attitudes, the heritage language was typically not passed down, leading eventually to situations where some German-speaking grandparents could not converse with their Israeli-born grandchildren. Language-related isolation was common, and linguistic enclaves formed in the middle-class communities.

Austrian Jews largely found it easier to acquire the language and to integrate into the Yishuv. Many had more previous contact with Judaism and Hebrew and felt less attached to their country of origin. It must be emphasized that Yekkes did make efforts to learn Ivrit. However, after a long day of work, they were often reluctant to open a vocabulary textbook, and the system of intensive language courses known as Ulpan was not introduced until 1948.

Fig. 5: Advertising column with posters in Hebrew and English, around 1934. The columns for outdoor advertising originally came from Berlin, where they were first installed in 1855; photograph by Hans Casparius (1900–1986), Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek.

Yekkes also had access to a wide range of German-language books, such as through lending libraries. Many brought their personal libraries with them, including complete matching sets of German classics, which were treasured as personal mementos until, decades later, they were discarded on the roadside during estate clear-outs after their owners’ deaths. The Schocken Library in Jerusalem, with its extensive collections – including the world’s largest Goethe collection – became an intellectual haven for many Yekkes. Another important linguistic arena that highlights the transnational nature of their diaspora was the press. For example, the Jüdische Rundschau from Berlin and the Prager Tagblatt from Prague were distributed in Palestine until 1938–39, while the Jüdische Welt-Rundschau, published in Jerusalem, was sent to Paris and from there distributed to over 60 countries until 1940. By the late 1930s, more newspapers and magazines were published in German in Palestine than in any other language. Among them was the Yedioth Hadashoth (Latest News), with a circulation of around 30,000 copies. The long-time editor-in-chief of the paper, which was renamed Israel-Nachrichten in 1974, was journalist Alice Schwarz-Gardos (1916–2007). She wrote numerous editorials and reviewed German television programs, including the German version of the popular quiz show Who Wants to Be A Millionaire? The Israel-Nachrichten, the last German-language newspaper in Israel, ceased printing in 2011 and continued online from 2013 to 2023.

According to Rabbi Shalom Ben-Chorin (1913–1999), who moved to Mandatory Palestine in 1935 and co-founded the Association of German-speaking Writers in Israel 40 years later, it is impossible to emigrate from one’s mother tongue. With a few exceptions such as Max Brod, German-speaking writers particularly struggled to continue their careers in Palestine. Literary salons, such as the one hosted by Nadja Taussig (1905–1998) in Tel Aviv, where Ben-Chorin, Brod, and Schwarz-Gardos were regulars between 1941 and 1992, provided an important platform. The common language of origin would prove to be the strongest bond within the German-speaking Jewish community in Palestine/Israel, allowing for the cultivation of a collective identity. In daily life, this often manifested in dialectal speech. Ultimately, Yekkes maintained a linguistic identity that was less about being “German” and more about speaking the language’s diverse dialects, from Hamburg’s Plattdeutsch to the Alpine dialect of Styria.

A diaspora always develops in relation to other identities, as a way to counteract feelings of alienation. German-speaking Jewish groups in Palestine did not exist in a vacuum, but existed as a minority within a Jewish minority. In 1922, Jews made up only 11 percent of the total population (752,000) and around 89 percent of the population were Arab, mostly Muslim. During the Fifth Aliyah, the Jewish share of the population more than doubled from 1931 to 1936, reaching 27 percent. Arabs responded to these changes in their own homeland of Palestine with resistance, increasingly expressed through violence. Larger riots had already occurred in 1920–21 and 1929, culminating in the Arab Revolt from 1936 to 1939 and numerous terrorist attacks. In response, the British Mandatory government limited Jewish immigration to 75,000 people over the next five years – right in the middle of the Second World War, during which six million Jews were murdered. Through Aliyah Bet – illegal immigration – over 100,000 persecuted Jews managed to escape to Palestine by 1948.

Nowhere else did the German-speaking Jewish diaspora encounter such violent rejection as in Palestine, where militant Jewish underground organizations responded in kind with violence. Many Jews avoided interactions with their Arab neighbors, whom they perceived as a threat, although there were also connections and positive relationships. Particularly in mixed cities such as Haifa, doctors’ offices, cafés, and sporting clubs served as meeting places, and Jews and Arabs sat by side on the city council. In 1942, the political arm of the IOME, known as Aliyah Hadasha (New Immigration), achieved gains there. This young party, which presented itself as a voice of opposition for all voters, not only German speakers, demonstrated the group’s desire to shape its new home politically as well. Until 1948, the moderate Aliyah Hadasha opposed the partition of Palestine. In this, it continued the legacy of Brit Shalom (Covenant of Peace), founded by German-speaking intellectuals in 1925, which advocated peaceful coexistence in a binational state. Its members were shaped by the ideals of humanism and a German-Jewish value system, in which many Yekkes took pride. Yet Brit Shalom remained a marginal group that did not significantly influence discourse in the Yishuv. Austrian Jews in particular, but also some German Jews, often rejected its pacifist, coexistence-oriented stance.

Fig. 6: The doctor Lola Baer from Nahariya also treated the sick from the surrounding Arab villages, 1941; Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem, PHKH\1260732.

The relationship between Jewish groups from Eastern Europe and those from the German-speaking world was generally strained, with the Yekkes often stirring the pot. They tended to view the Ostjuden (Eastern European Jews) as uncivilized, while many Yishuvniks perceived them as arrogant aesthetes whose stubborn loyalties to people from their regions of origin endangered the Zionist project. This tension was compounded by the fact that around a fifth of the Yekkes had their own (earlier) Eastern European roots, which they had cast aside due to their own experiences of discrimination in Germany. Eastern European Jewish immigrants to Germany had not always received a warm welcome.

Now, in Palestine, the Yekkes were the newcomers, facing employers and landlords from Eastern Europe whose business practices favored their own group economically. This nepotistic practice, known as protektsiya, was also criticized by other groups of German-speaking Jews, and underscored the need for mutual aid as defined by their shared geographical origins. The war of 1947–49 and Israel’s declaration of independence eased the often-mutual wariness between these groups. External threats and conflicts with other groups ultimately led the Yekkes to become loyal citizens of Israel, the place of refuge that had saved their lives.

Although there were plenty of cases of (temporary) return migration before 1933, few of the German-speaking Jews who went to Palestine/Israel ever left. One exception was the German-speaking writer Arnold Zweig (1887–1968), who had failed to attract a Hebrew readership and, disillusioned with socialist Zionism, settled in East Germany. Others, like the sex therapist Ruth Westheimer (1928–2024), left due to the tense political situation – in her case, after being injured in Israel’s War of Independence. Meanwhile, German-speaking Jews continued arriving in Israel, including those who had survived the Shoah in formerly occupied Europe. Many of them maintained personal connections to their birth country, connections that were crucial for the various networks of this transnational diaspora.

These connections also led to joint efforts for restitution. As early as 1943, the Mitteilungsblatt demanded reparations (Wiedergutmachungen). In 1945, the publication co-initiated the international Council of Jews from Germany, of which the IOME was a member. Some later traveled to their countries of origin, primarily West Germany, to file claims for compensation. Others, such as the philosopher of religion Gershom Scholem, maintained contacts with universities in their countries of birth and visited on his lecture tours. However, many never set foot in Europe again. While some fled the hot Israeli summer for the Bohemian woods or the Black Forest, others ruled out even a short stay. The Central Committee of Jews from Austria in Israel began its work in 1996 as the umbrella organization for Austrian Jews. Based in Tel Aviv, the association was established with the support of the National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism. It represents Austrian Jews and their descendants before the authorities in Austria, while it also preserves the cultural heritage of this group and creates spaces for encounter. With a club that offers a German lending library and regular events – including a ‚coffee and cake‘ style breakfast – it enables its members in Israel to maintain cultural ties with Austria.

Overall, German-speaking Jews’ relationships with their countries of origin varied greatly and often evolved over the course of their lifetimes. In old age, nostalgic reminiscences became more common, and many German Jews participated in group visits organized by individual cities. The German-speaking Jewish diaspora in Israel has remained dynamic even though it has not always been visible. In particular, the children and descendants of immigrants have primarily viewed themselves as Israelis, while the older generation often retained a sense of dual identity. For many, connections to a region provided a way to reconcile these identities. This is evidenced by the numerous “former residents” clubs, such as the Association of Jewish Former Residents of Hamburg, founded in Jerusalem in 1984.

Since 2000, a larger group of descendants has returned to Europe, particularly Berlin. Some have consciously explored their Yekke roots there, but most are attracted by life in a European metropolis that has fewer political tensions and a lower cost of living. Especially after the terrorist attack by Hamas on October 7, 2023, many are exercising their right to naturalization as descendants of persecuted Jews.

One key element of a diaspora is that it creates its own spaces of memory, which help to shape its members’ identities. In Israel, this process began in 1955, when German-speaking intellectuals founded the Leo Baeck Institute (LBI), which sought to preserve the legacy of German-speaking Jewry through critical scholarship. In addition to its own archive, the LBI, which has operated and published in Hebrew since the 1970s, oversees the Jüdischer Almanach (Jewish Almanac). This annual publication is released in Berlin and was dedicated to the subject of “Yekkes” in 2005. Over the past four decades, interest in this group’s history has grown significantly in Israel, where more space is now accorded to the diversity of immigrant cultures beyond the Zionist melting pot. This was demonstrated by a multi-day conference on German-speaking Jewish cultural heritage held in Jerusalem in 2004. Many of the attendees had personally lived through key periods of this history.

In addition to scholarly research, Israel Shiloni, born in Berlin in 1901, laid the foundation for museum-based commemoration. In 1968, he established the German-Speaking Jewry Heritage Museum in Nahariya, which relocated to the Tefen Industrial Park in 1991. Until its closure in 2020, the museum hosted a permanent exhibition focused on Yekkes’ contribution to Israel’s growth and development. Since 2021, its holdings and its archive have been housed at the University of Haifa, which remains interested in the papers of German-speaking Jews. This angle on the history of the group’s “contribution,” which also structured exhibitions in Germany, was predominant for many years.

Indeed, German-speaking Israelis, including many Yekkes, have left a lasting impact on the country, particularly in its health and social services, universities, press and publishing, retail, industry, and banking and hospitality sectors. Their influence is still visible today, for example, in the Bauhaus architecture that found its way to Tel Aviv thanks to architects such as Lotte Cohn (1893–1983). Most German-speaking Jews (especially women) found it difficult to gain a foothold in the political arena, however. Exceptions included Pinhas Rosen and Teddy Kollek (1911–2007), who was born in Hungary and served as mayor of Jerusalem for nearly 30 years.

With their experience of democracy and usually liberal view of the state, the Yekkes offered a counterbalance to the socialism of many former Eastern Europeans. Today, as Israeli politics continues to radicalize rightward, institutions of memory such as the LBI call attention to the cultural heritage of German Jewry, which includes Reform Judaism. One of the first Reform (or Liberal) congregations in Palestine was Emet ve-Emunah (Truth and Faith), whose ties to clubs for members with shared regional origins allowed congregants to practice their religion in ways familiar from the Old Country. Rabbi Kurt Wilhelm, who advocated for Arab-Jewish dialogue, led the congregation until 1948. The broad cultural heritage of German-speaking immigrants was not transmitted intact, and aspects were lost. From the outset, interactions and hybridities emerged – as in the case of Emet ve-Emunah, which transformed into a Hebrew-speaking Orthodox congregation that still exists today.

A vibrant German-speaking diasporic culture no longer exists in contemporary Israel. The IYME still has about 2,000 members who receive its bimonthly magazine, now renamed from the German Mitteilungsblatt to the Hebrew Yakinton. Alongside articles aimed at gaining recognition of the group’s contribution, personal memories have become more prominent, reflecting both losses and gains, homesickness and making oneself at home. German-speaking Jews, as a heterogeneous group, have ultimately found their place in Israeli society. Their cultural socialization, which many clung to with pride despite the Zionist assimilationist narrative, is now largely viewed positively. Yet the road to Eretz Israel was rocky and rarely chosen voluntarily. Thanks to a collective diasporic culture, these newcomers did not have to walk that road alone. In their frequent struggles to adjust, many German Jews used self-deprecating humor as a coping mechanism. For example, the IYME distributed Hebrew stickers a few years ago with the phrase “Yekke at the steering wheel,” an inside joke that probably only lands in Israel.

Online Exhibitions, Databases, Digitized Material, Commemorative Projects and Associations

The Yekkes. A virtual museum by Jeckes Cologne – Jüdisches Leben in Köln e.V.: https://jeckesmuseum.de/index.html

Irgun Yotzei Merkaz Europa (IYME), Association of Israelis of Central European Origin (in Hebrew and English: https://irgun-jeckes.org

The Central Committee of Jews from Austria (in Hebrew and German): https://www.zkjo.org

Library of Lost Books. A provenance research project by the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem and London: Chapter 1 - Leo Baeck Institute

Theodor-Herzl-School Berlin (1920–1938). A remembrance project by former students, editing and distribution, Amir Teilhaber: https://theodor-herzl-school-berlin.org/

The Austrian Heritage Archive (AHA): https://austrianheritagearchive.at/en

Second generation German-speaking Migrants in Israel. Archiv für Gesprochenes Deutsch. Access via https://dgd.ids-mannheim.de/dgd/pragdb.dgd_extern.welcome

Autobiographical interview with Gad and Miriam Elron, who were both born in Berlin in 1918 and 1922, respectively, and emigrated in the 1930s to Mandatory Palestine, 1991; National Library of Israel: https://www.nli.org.il/en/audio/NNL_ALEPH990044225040205171/NLI

Digitized issues of the MB (1932–1939): Compact Memory / Mitteilungsblatt der Hitachduth Olej Germania

Digitized issues of the MB (1939–1943): Compact Memory / Mitteilungsblatt der Hitachdut Olej Germania we Austria

Digitized issues of the MB (1943–2006): https://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/cm/periodical/titleinfo/12662843

Digital issues of the MB Yakinton (2006–): https://irgun-jeckes.org/category/mb-digital

Films and Podcasts

Die Wohnung – Film by Arnon Goldfinger, 2011; Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: https://www.bpb.de/themen/nationalsozialismus-zweiter-weltkrieg/die-wohnung/201097/die-wohnung-der-film/

It’s Harder for Yekkes – Film by Yuval Gidron, 2015; Berliner Landeszentrale für politische Bildung: https://www.berlin.de/politische-bildung/politikportal/blog/artikel.952045.php

Back to the Fatherland – Film by Kat Rohrer and Gil Levanon, 2017: https://backtothefatherland.com/#top

Schawei Zion – a Swabian Village on the Mediterranean, 02/26/1965; SWR Retro-Abendschau: https://www.ardmediathek.de/video/Y3JpZDovL3N3ci5kZS9hZXgvbzExNjU4OTU

Podcast – Haifa Center for German and European Studies (HCGES)

Exile Podcast of the Leo Baeck Institute New York | Berlin presented by Mandy Patinkin, 2023: Episode 12: Before Dr. Ruth: The Story of Ruth Westheimer - Leo Baeck Institute

Viola Alianov-Rautenberg on German-Jewish migration movements to Mandatory Palestine and the significance of the category of gender, 2023: #39 Jüdische Geschichte Kompakt – No Longer Ladies and Gentlemen - wissenschaftspodcasts.de

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Lisa Sophie Gebhard is a historian and research associate at the Moses Mendelssohn Center in Potsdam. Her past research focused on the history of Zionism, including co-editing the anthology German-speaking Zionism(s). Advocates, Critics and Opponents, Organizations and Media (1890–1938). Most recently, her dissertation was published and presented at the Leipzig Book Fair in 2023 under the title Davis Trietsch - A Forgotten Visionary. Zionist Ideas for the Future between Germany, Palestine and the USA. She lives with her family in Berlin.

Lisa Sophie Gebhard, Homecoming to a Foreign Country. German-speaking Jews in Palestine/Israel (translated by Jake Schneider), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-1> [February 22, 2026].