In modern Jewish history, France holds a special status. ‘Happy as a Jew in France’ – the expression, which refers to the fact that Revolutionary France gave Jews citizenship rights in 1791, turned into the opposite for those Central European Jews who fled there to escape Nazism. “The Devil in France” Lion Feuchtwanger, Der Teufel in Frankreich: Erlebnisse. 1940 (1st ed. 1942 Unholdes Frankreich), Berlin: Aufbau, 2018. became the famous wording by the German-Jewish novelist Lion Feuchtwanger (1884–1958) to describe his personal experience in France.

France was a preferred destination for Jewish refugees in Europe in the 1930s and an important site of transmigration. It became the leading host country of temporary German-speaking Jewish diaspora networks in Europe, where various political associations, cultural clubs, and newspapers were founded. For those persecuted, France represented the country of human rights. It was considered a haven of refuge because of its liberal asylum policy in the nineteenth century. Yet this was sorely tested in the 1930s: in a state of permanent crisis, France was caught up in the consequences of the economic depression, overwhelmed by the influx of refugees, and confronted with growing antisemitism.

Even so, France took in more refugees than any other country during the 1930s: of the approximately 500,000 Jewish refugees from Nazism (including the annexed territories), around 150,000 passed through or stayed in France. Torn between its tradition of hospitality and political and economic imperatives, France was unable to develop a genuine policy towards refugees. Worse – it turned against those it had welcomed and arrested, interned, and deported Jewish refugees to the death camps.

Since the end of the nineteenth century, successive waves of immigration have led to the formation of a small German-speaking Jewish community in France. In the interwar period, Jews born in France were a minority. According to the 1931 census, the Jewish immigrant population totaled over 200,000 (a significant proportion of whom were transmigrants) out of a Jewish population of around 300,000, to which should be added some 100,000 Jews in Algeria. The German-speaking Jewish diaspora (from Germany, Austria, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia) in France numbered a few tens of thousands prior to 1933.

While political opponents left Nazi Germany in the spring of 1933, the departure of most Jews from Germany and Austria was spread out over several years in waves of emigration that depended on Nazi antisemitic policies and the state of international relations. In 1933 alone, 60,000 people left the German Reich, half of whom took refuge in France. Over 75 percent of these were Jewish. Additionally, about 2,500 undocumented migrants arrived in France without legal permits. Jews who were not politically active left Germany gradually. Some in April 1933, after the boycott of Jewish shops; others, more numerous, following the 1935 Nuremberg Laws; still others, after the pogroms of November 1938. Of these, 60 percent were German nationals, while 40 percent were Jews of Eastern European origin who did not hold German citizenship. After the annexation of Austria in March 1938, Austrian-Jewish refugees began arriving as well.

Most refugees came from larger cities, such as Berlin, Frankfurt, Breslau (Wrocław), Hamburg, Cologne, Leipzig, or Vienna. They belonged to the middle class. In terms of socio-professional distribution, relatively accurate statistics are available for the period prior to 1936. The proportion of blue-collar (10 percent) and white-collar workers (10 percent) was fairly low, while that of craftsmen and tradesmen exceeded 40 percent; there were 20 percent students and 20 percent members of the liberal professions, intellectuals, and artists. Most emigrants were young: 75 percent of them were aged between twenty-five and forty years. Between 1933 and 1936, the majority of Jewish refugees were single, and fewer women emigrated to France than men.

Although it is difficult to provide precise figures, it appears that a total of 150,000 individuals passed through the country between 1933 and 1943 for varying periods, ranging from a few days to several years. Taking into account transmigrations and forceful repatriations, the total number of German-speaking Jews living in France between 1933 and 1944 never exceeded 60,000. Among those were around 12,000 Austrians who fled after the annexation of their homeland. The 7,500 Jews from Baden-Württemberg and the Palatinate, who were deported in October 1940 and interned in camps in the south of France, must also be counted as refugees.

While France was the top destination in 1933, it was probably the only country, apart from Switzerland, that had more refugees leaving than arriving. Nevertheless, France remained the fourth most important destination for emigration, after Mandatory Palestine, the United States, and Great Britain. And with around 7,000 to 10,000 survivors, France had the most survivors and returnees of countries that were under Nazi influence during the war. Against all odds, the majority of German-Jewish survivors decided in 1944/1945 to remain there. Among them was the painter Stanislaus Bender (1882–1975), who had survived with his daughter in Lourdes with the help of the local bishop. Eventually, a few years before he died, Bender decided to return permanently to his hometown of Munich.

While France initially issued visas generously and allowed refugees to enter the country without valid papers, the harassment soon began. Faced with an influx of refugees, the government decided in December 1933 to reduce the number of visas and to carry out border refoulements and expulsions. From 1934 onwards, growing political tensions resulting from the global economic depression began to impact the country’s immigration policy, which became increasingly more restrictive.

In 1935, the French government tightened its policy even further, henceforth tolerating only foreigners holding a work permit. In 1934 and 1935, 40,000 to 50,000 Jewish refugees were forced to leave France: the number of departures exceeded the number of arrivals. In the absence of a global solution, the left Front Populaire, which came to power in 1936, decided on a provisional solution by creating a ‘certificate of identity for refugees from Germany’, which conferred refugee status on emigrants who had arrived in France between 30 January 1933 and 5 August 1936.

Fig. 1: “Comment la France absorbe-t-elle l’immigration judéo-allemande? (“How is France absorbing German-Jewish immigration?”)”, in: Excelsior, 22 January 1934, 1; Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Unfortunately, this precarious equilibrium did not last long. In 1938, the legal situation of emigrants from Germany and Austria worsened. In May, under the pretext of security policy, Prime Minister Édouard Daladier’s (1884–1970) newly appointed government passed new decree-laws regulating more strictly the conditions of residence and policing of foreigners. These restrictions were followed by house arrests at the end of 1938, a ban on ‘foreign propaganda,’ strict control of foreign publications, the dissolution of foreign associations in the summer of 1939, and, finally, the administrative internment of former German and Austrian nationals from autumn 1939. As a result of losing their nationality, most Jewish refugees had by then become stateless. Those who had been unable to leave across borders for a second flight were subsequently arrested between September 1939 and May 1940, sent to camps, or forced to flee in the face of German troops.

When war was declared, refugees became ‘enemy aliens’ and, as early as September 1939, internment began. From then on, Jewish refugees were persecuted by both Nazi Germany and Vichy France. Of the 40,000 Jewish refugees living in France in 1939, around 20,000 were able to leave the country in time. The rest found themselves categorized as ‘foreign Jews,’ which placed them at high risk of arrests and abuse.

The first refugee internment camp opened in 1939 at Rieucros (Lozère) and another at Gurs (Basses-Pyrénées). Though initially intended to intern Spanish refugees from the Spanish Civil War and members of the International Brigades who were recruited by the Communist International to fight in Spain, the camps came to hold a large number of German and Austrian Jews.

After France’s defeat in June 1940, Jewish refugees, if they wanted to survive, had to live with false papers or go into hiding. The Armistice Agreement of 22 June 1940 had divided France into zones. The occupied zone, which comprised the areas north of the Loire and the entire Atlantic coast, was under German military control based in Paris. The Départements Nord and Pas-de-Calais were placed under the jurisdiction of the German commander in Brussels, while the eastern Départements were incorporated into the German Reich. Part of the south-eastern Départements was under the control of the Italian occupying forces until Fascist Italy’s defeat in September 1943.

The unoccupied zone, on the other hand, comprised the remaining Départements of southern France, the overseas territories, and the colonies. The destruction of the political, social, and economic status of Central European Jews living in France began in the summer of 1940 in both the unoccupied and occupied zones. Article 19 of the Armistice Agreement stipulated that all ‘Germans’ living in France and the French colonies, the majority of whom were Jews, were to be extradited to Nazi Germany on request. Moreover, following the law of 22 July 1940, a so-called naturalization review commission re-examined the naturalizations granted since 1927 and withdrew French nationality from around 6,000 Jews.

The Vichy regime that controlled the territories not annexed or occupied by the Axis Powers implemented antisemitic state policies. A host of statutes and laws were quickly introduced, which placed Jewish refugees in immediate danger since they allowed prefects to place ‘foreigners of the Jewish race’ under strict police surveillance. The arrests of foreign Jews took place with almost general public indifference. Internment continued to increase in the non-occupied zone and spread across camps such as Le Vernet (a repressive camp), Gurs (a semi-repressive camp), Bram, Argelès, Saint-Cyprien, or Les Milles (where foreigners awaited emigration). Other detention centers, such as Rieucros and Agde, housed both foreigners (Jews and non-Jews) and French ‘undesirables,’ particularly Communists. In February 1941, there were about 40,000 Jewish internees in French camps, representing 75 percent of the total interned population.

Fig. 2: Arthur Schmitz (marked with x) eating at an outdoor table in Les Milles internment camp, 1940. Schmitz was born in Vienna in 1908. At the age of thirty, he fled to France and was interned. He immigrated to the United States around 1940; Arthur Schmitz Collection AR 10951, F 26824, Leo Baeck Institute.

The Vichy regime continued to exacerbate its anti-Jewish policies and, in 1941, introduced measures meant to solidify the separation and removal of Jews from French society. With the first transport to Auschwitz on 27 March 1942, the ’implementation of the Final Solution’ in the country began. In the summer of 1942, the French camps were sealed off, and so-called screening commissions steered mass deportations to the East. After the demarcation line between the occupied and unoccupied zones fell in November 1942, Nazi measures against Jews were applied throughout the country. Between 1942 and 1944, of the 75,721 Jews deported from France, an estimated 7,000 were of German and 2,500 of Austrian origin, many of them children.

Deprived of legal status, the German-speaking Jewish refugees had to endure long waits at the Préfecture de Police; they were in constant danger of being deported and had to use their wits to find work in a country that denied them any legal means of earning a living. In 1936, under the government of Léon Blum (1872–1950) and his Front Populaire, a centralized aid committee for those fleeing Nazi Germany had been set up. In general, refugees became increasingly dependent on the help of private organizations. The political conditions in France during the 1930s and the surrender to Nazi Germany in 1940 led German-speaking refugees to once again seek routes of flight. In this context, a global network of organizations began coordinating efforts out of the country. Transmigration routes were varied and included crossing the border to Spain, reaching French colonies in North Africa or in the French Caribbean, sailing from the southern port city of Marseille towards Mandatory Palestine, or westwards towards the United States via the Atlantic Ocean.

During the summer and autumn of 1940, the activities of the various relief committees working to evacuate refugees from France gathered pace. These included collecting funds to cover travel costs, lobbying governments, providing financial aid and other kinds of support to refugees in France – in and outside of internment camps – and, in some cases, falsification of papers. The Marseille-based Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC), headed by the American journalist Varian Fry (1907–1967), attempted to facilitate the departure of prominent exiles from France by issuing special visas and forging passports, with the goal of smuggling them via Spain or Casablanca to Portugal and the United States. Among the refugees who made this journey were prominent figures like the intellectuals Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) and Siegfried Kracauer (1889–1966) or the writers Lion Feuchtwanger (1884–1958) and Anna Seghers (1900–1983), who immortalized the refugees’ situation in Marseille in her novel Transit (1944), which she wrote during her second exile in Mexico. Not all refugees were successful in fleeing France. The German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) attempted to reach Spain in September 1940, hoping to leave the country via Portugal with a visa for the United States. Under constant fear of arrest and subsequent extradition to Germany, Benjamin took his life in the Spanish border town of Portbou.

Fig. 3: Anna Seghers in Meudon Bellevue with her husband László Radványi (1900–1978) and their children Pierre (1926–2021) and Ruth Radványi (1928–2010), around 1936/37; Collection Pierre Radvanyi, Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration.

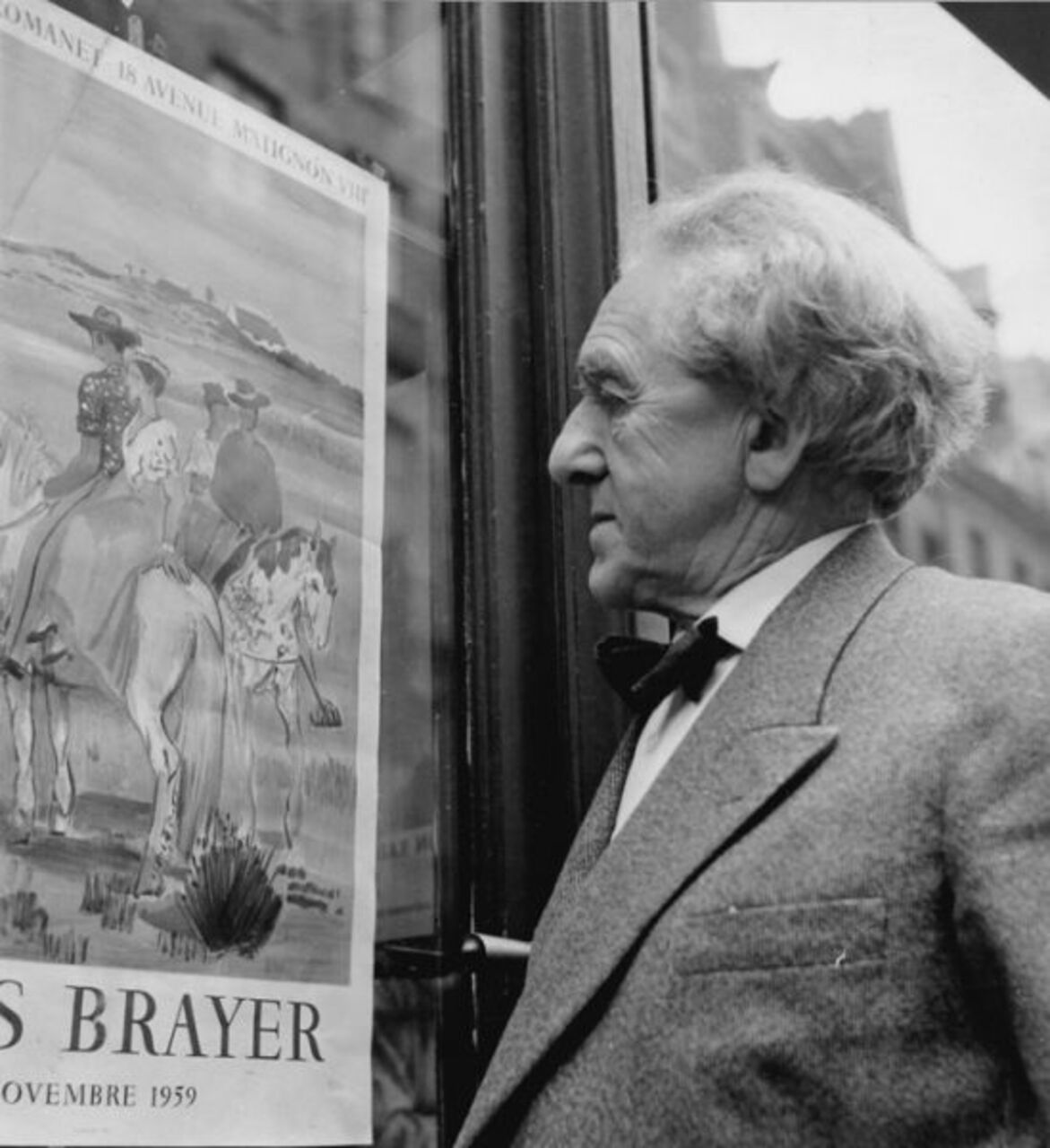

Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, the vast majority of German-speaking Jewish refugees stayed in Paris. With a Jewish population of between 160,000 and 200,000 at different times during the 1930s, the Parisian Jewish community formed one of the largest communities in the world. At least 10,000 Jewish refugees from Central Europe lived in the French Capital throughout the 1930s. No single German-Jewish refugee neighborhood emerged at this time. Some lived in the bourgeois 16th arrondissement or Neuilly, others in working-class districts such as Belleville, where the comparatively low cost of living attracted newcomers. There were also notable, though smaller, refugee communities in the cities of Lyon, Nice, and especially Marseille, where the paths of numerous German and Austrian Jews crossed. Sanary-sur-Mer, a small fishing village on the French Riviera, is also worth mentioning as a temporary hub for German-speaking Jewish intellectuals between 1933 and 1940. The painter, art dealer, and photographer Walter Bondy (1880–1940), born in Prague and raised in Vienna, portrayed many of them in his photography studio. Bondy had left Berlin as early as 1932 and moved to France due to the rising antisemitism. Several exiled artists and families from Sanary-sur-Mer had their portraits taken at his studio, which he and his wife Camille Bondy (1910–2009) transferred in 1937 to Toulon.

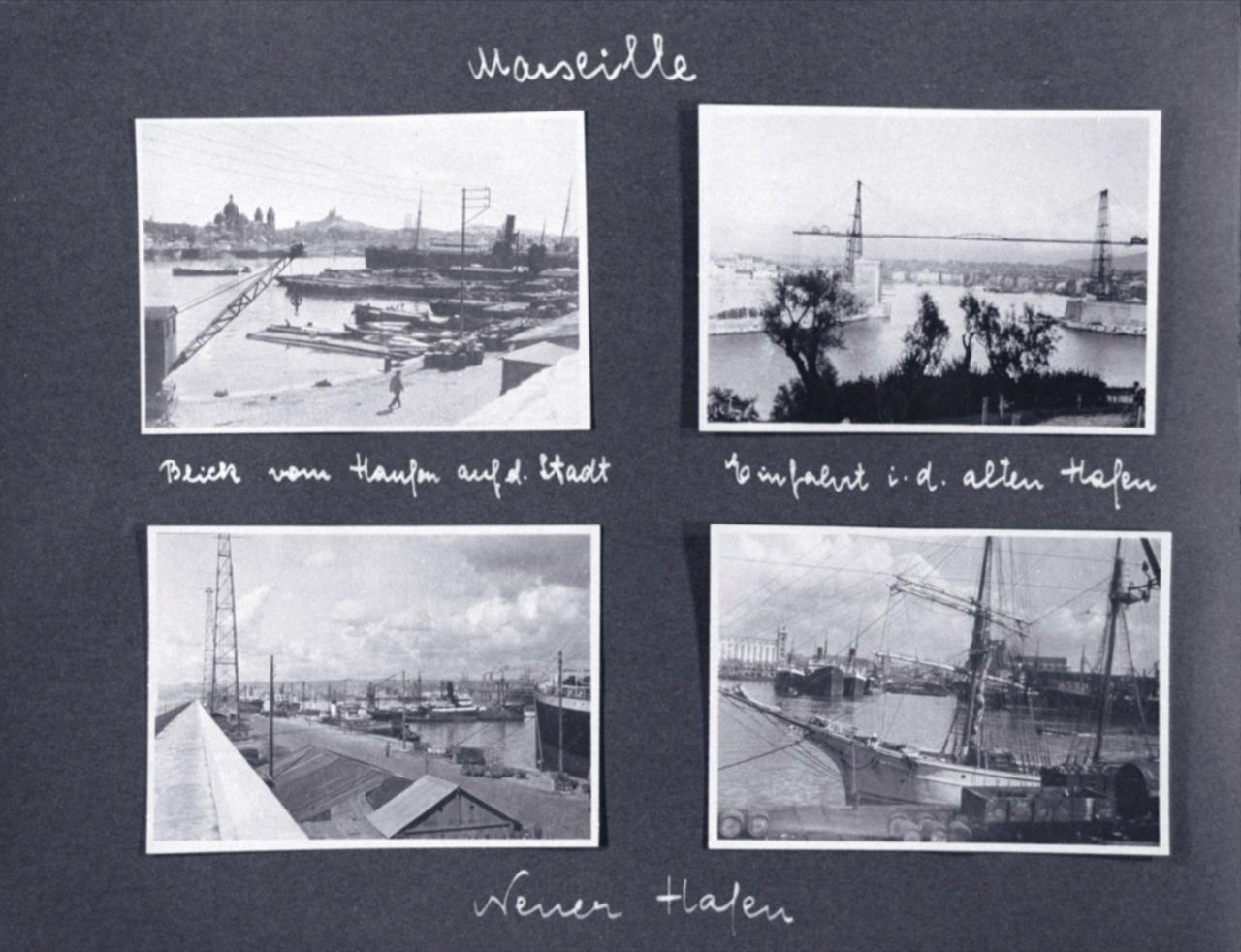

Fig. 4: Family album with photographs from Marseille belonging to Gertrud Maria Kurth (1904–1999), 1930s. Kurth was born in Vienna and traveled to France in the 1930s. She had to flee Austria in 1939 and finally immigrated to the United States; Gertrud Kurth Collection AR 10905, ALB 14, Leo Baeck Institute.

The history of German-speaking Jewish diasporic spaces in Paris is also one of cultural and intellectual transfer, which emerged in specific locations. Rue La Boëtie, for example, is associated with the Pariser Tageblatt, which was first published on 12 December 1933 by journalists who had previously written for Weimar liberal-left newspapers. The German-language newspaper, which relied financially on advertising, conveyed the features of everyday life in the host country. In June 1936, the editorial team re-founded the newspaper under the name Pariser Tageszeitung. It ceased publication after the Nazi occupation of France in 1940.

The German-speaking Jews created their own spaces of diasporic life. One such place was the first German-language bookshop in exile, Au Pont de l’Europe, which was founded in Paris by Ferdinand Ostertag (1893–1963) in March 1933. Ostertag, who was born in Glogau (Głogów), Lower Silesia, had left Berlin for Paris in 1931. His Parisian bookshop became a meeting place for German and French anti-fascist authors. Ostertag was interned in September 1939, and his bookshop closed in May 1940. He was interned again in November 1940, first at Gurs, then at Les Milles. His transatlantic crossing was organized by Varian Fry’s ERC. Ostertag arrived in New York in November 1941 and died there in 1963.

In a way, this tradition was revived after the war, with the opening in 1951 of the Calligrammes bookshop on the premises of a former watchmaker’s shop in the Parisian intellectual heart of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Calligrammes became a meeting point for former refugees, young German postwar authors, and French readers interested in Germany. Founded by Fritz Picard (1888–1973) and Ruth Fabian (1907–1996), both of German-Jewish origin, the bookshop existed until the late 1980s.

Fig. 5: Fritz Picard in front of the shop window of his Calligrammes bookshop in Paris, around 1966; © Ulrike Ottinger.

Research into the diasporic spaces of German-speaking Jews in France over the last fifty years followed successive trends: scholars showed a greater interest in refugees from Germany than from Austria; few monographs take into account the fact that France simultaneously took in other refugees, for example, anti-Franquists. For a long time, the memorialization of the German-speaking Jews’ presence in France was dependent on political activities, to the detriment of an interest in diasporic dynamics and public commemoration. Indeed, a significant proportion of German and Austrian Jews took part in political activities in the journalistic and editorial field and actively participated in the resistance against the Nazi occupation. Yet their everyday lives and other social and cultural activities had long been overlooked.

In 1982, half a century after the flight, a group of German Studies students at the University of Paris 8 interviewed and filmed ‘former Germans’ who had fled Nazism and chosen to stay in France, including the writer and translator Georges-Arthur Goldschmidt (*1928) and the journalist and teacher Lotte Schwarz (1902–1984). Their documentary is entitled Exile ‘33, Paris ’82 and is a rare first-hand account of the difficulties of acculturation in France and the complex relationship with the Heimat of origin.

Thanks to the work of individuals like Serge (*1935) and Beate Klarsfeld (*1939), the history of Central European Jewish refugees was finally inscribed into the larger history of the Shoah. Not until the mid-1990s did French President Jacques Chirac (1932–2019) and Prime Minister Lionel Jospin (*1937) acknowledge France’s problematic role. The research established a continuity between the end of the Third Republic and the Vichy regime, showing that the antisemitic policy introduced from 1940-41 was in line with the administrative discrimination suffered by all foreigners in 1939. French internment camps played a direct part in the collaboration with Nazi Germany and the annihilation of European Jewry. Among all camps, Drancy, the largest, had a special status: 70,000 Jews were interned there in the four years of its existence, and 75 percent of all Jews deported from France passed through Drancy. The Wall of Names (Mur des noms), part of the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris, is a reminder of this history. It consists of three walls on which are engraved the names of the 76,000 Jews deported from France.

The memorialization process took place on both sides of the Rhine. As early as 1955, the West-German journalist Peter Adler (1923–2012) revealed that elderly refugees who had fled Nazi Germany were living in Paris in degrading conditions. In 1956, a documentary followed: Die Vergessenen (The Forgotten), directed by Peter Dreessen (1925–?). As a result, the German Parliament voted an emergency aid. With the aid collected, Solidarité, the association of Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria, which was re-established in 1953, purchased a castle in Limours near Paris and provided forty German-Jewish emigrants in need of assistance with a new home. This was the subject of another documentary in 1957, Das Haus der Vergessenen (The House of the Forgotten) by Dieter Ertel (1927–2013). Founded before the war, but revitalized in the early 1950s with transnational links to organizations in London, New York, and Tel Aviv, Solidarité’s core was a network of Jewish jurists who had belonged to the Weimar elites. Their goal was to find solutions to the everyday hassles of its approximately 1,300 members and to defend the collective interests of former German nationals of Jewish origin who had survived in France. Solidarité helped them assert their rights to compensation with the West-German authorities. The association also embarked on a social housing program to accommodate its members: in addition to Limours, it acquired buildings in Paris and the suburbs of Vanves and Kremlin-Bicêtre. Solidarité continued to exist well into the first decades of the twenty-first century.

Around a hundred German-Jewish families had settled in the Lyon suburb of Villeurbanne. It was here that the Fraternité-Synagogue was built, the result of a joint effort by Villeurbanne’s (German-)Jewish community, the municipality, and the West-German movement Aktion Sühnezeichen. The foundation stone, laid in April 1963, was donated by the State of Israel.

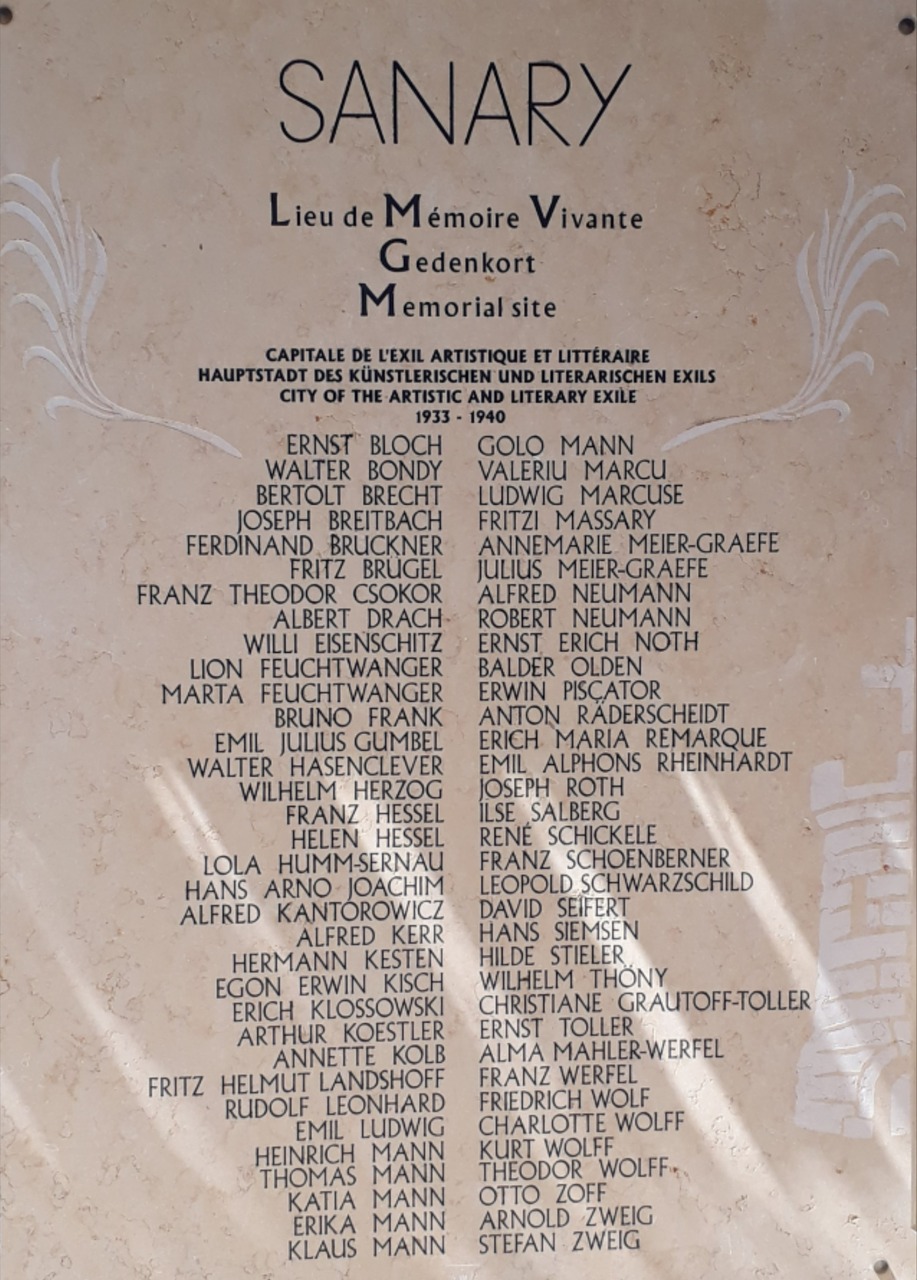

In the 1980s, interest began to focus on preserving the memory of the exile in southern France. In 1989, a discrete ceremony was held at the tilery in Les Milles: the municipality had bought a building to create a museum-memorial, which finally opened in 2012. Sanary-sur-Mer, the small town on the Mediterranean coast which the German philosopher Ludwig Marcuse (1874–1971) had called the ‘capital of German literature,’ also became a memorial site. In 1987, a plaque was unveiled with the names of prominent German and Austrian émigrés. While both Sanary and Les Milles have become references, the narratives surrounding both sites combine elements of shared memory – France as a haven of refuge – and of divided memory – France as a site of persecution.

Fig. 6: The memorial plaque for the persecuted German-speaking writers and artists at the harbor of Sanary-sur-Mer; City of Sanary-sur-Mer, Sanary Tourist Office.

What remains to be explored in the history of the temporary German-speaking Jewish diaspora in France? On the one hand, it is important to go beyond the ‘celebrities,’ mostly men. A number of those indeed had a lasting impact on French public life and the European reconciliation process: among them were the politician Daniel Cohn-Bendit (*1945), who was born to parents who had fled Berlin, the filmmaker Max Ophüls (1902–1957) from Saarbrücken, the physicist Pierre Radvanyi (1926–2021), who was born in Berlin to Anna Seghers or the writer Manès Sperber (1905–1984), who had arrived in Vienna at the age of eleven. Yet we know little about Jewish women refugees and their sociocultural impact, with the exception, for instance, of the film critic and archivist Lotte H. Eisner (1896–1983) and the photographer Gisèle Freund (1908–2000), both born in Berlin or the historian and human rights activist Rita Thalmann (1926–2013) from Nuremberg.

An important task for future research is to illuminate the multiple identities of Central European Jews who came to France seeking refuge. Little is known, for example, about the Eastern European members of the German-speaking diaspora. Polish Jews who arrived in France as refugees from Nazi Germany had a separate organization in Paris and Metz, the Association des Juifs polonais réfugiés d'Allemagne, founded in the summer of 1933. The transnational itinerary of Françoise Frenkel (1889–1975), a Polish Jew who studied in Paris, lived in Germany, and opened, in 1921, along with her husband, Simon Raichinstein (1889–1942), the only French bookshop in interwar Berlin, was recently retraced. Frenkel, born Frymeta Idesa Frenkel, came to France in 1939. In Nice, she was able to escape the roundup of 26 August 1942, while her husband was murdered in Auschwitz. After three unsuccessful attempts, Frenkel crossed into Switzerland, finally returned to Nice, and became a naturalized French citizen in 1950. These stories also constitute a part of the German-speaking Jewish diaspora.

Finally, it seems equally important to take a global, trans-imperial look at German-speaking Jews in pre-decolonization France. Nearly 15,000 Jews were interned in France’s various colonies in 1941, including refugees from Central Europe. For example, the French philosopher Hélène Cixous (*1937) was born in Oran, French Algeria, to a Jewish Algerian father and a German-Jewish mother who had been exiled from Germany. Yet despite recent research on North Africa or the French Caribbean, we know too little about those stories.

Following in the Steps of Exiled Writers. A virtual route in commemoration of the writers and artists who found refuge in Sanary-sur-Mer; City of Sanary-sur-Mer, Sanary Tourist Office: https://www.sanary-tourisme.com/en/discover-sanary/history-and-heritage/sanary-land-of-exile/following-in-the-steps-of-exiled-writers/

Brochure The Exile of the German and Austrian Writers in Sanary; City of Sanary-sur-Mer, Sanary Tourist Office: https://www.calameo.com/read/0060437613359332fdcdf

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Prof. Dr. Patrick Farges (https://ict.u-paris.fr/annuaire/patrick-farges/) is Full Professor of German & Gender History, and the Deputy Director of the College of Graduate Schools at Université Paris Cité. His research focuses on modern German-Jewish history, the history of exile and forced migration, and the history of masculinities in Nazi Germany.

Farges has published articles in Central European History, German History, Remembrance & Research. The Journal of the Israel Oral History Association, Annali. Sezione germanica, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, and Revue d’Allemagne et des pays de langue allemande. He authored Le Muscle et l’Esprit. Masculinités germano-juives dans la post-migration (Brussels, 2020), and co-edited with Elissa Mailänder Marcher au pas et trébucher. Masculinités allemandes à l’épreuve du nazisme et de la guerre (Lille, 2022).

Patrick Farges, A Home of Human Rights? The German-speaking Jewish Diaspora in France (1930s–1940s), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-13> [February 20, 2026].