Born on September 1, 1880 in Usch, Germany (today Ujście, Poland)

Died on July 4, 1950 in São Paulo, Brazil

Occupation: Banker,

art collector, agriculturalist

Migration: France, 1933 | Brazil, 1941

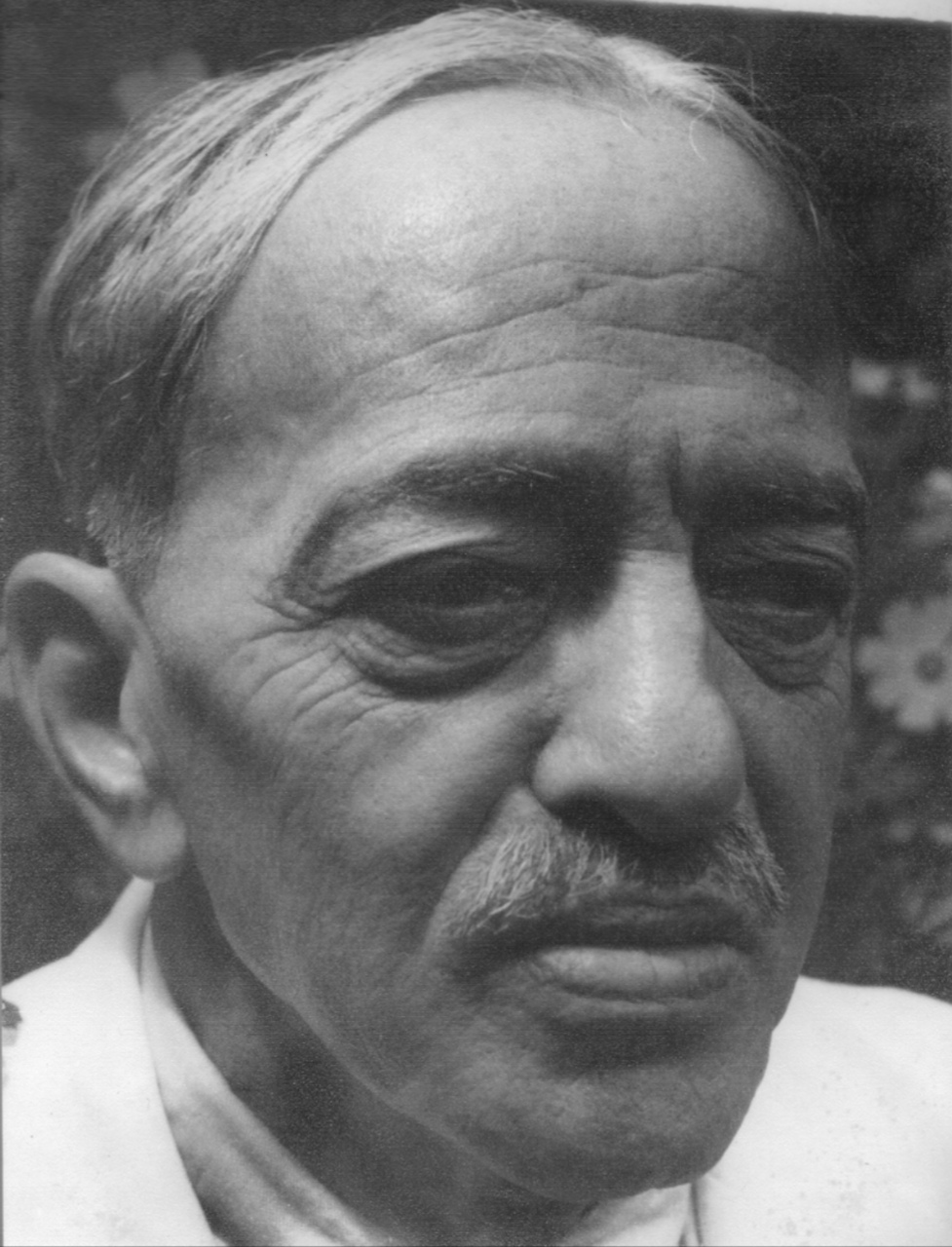

“I have no nationality.” American Foreign Service (Marseille), “Application for non-immigrant visa, no. 517 (Hugo Simon)”, 27.09.1940; Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933-1945, Frankfurt-a.M., Teilnachlass Hugo Simon. The phrase appears on application forms submitted by Hugo Simon for a non-immigrant visa to the United States, in September 1940, in response to the question about citizenship. Although probably a standard formulation for stateless applicants, those four words sum up the plight of many Jewish refugees fleeing persecution during the 1930s and 1940s. In Simon’s case, they carry distant echoes. Born in the then German province of Posen, he was accustomed from an early age to crossing cultural boundaries. Throughout his life, he was aligned with the ideals of international solidarity and pacifism, dedicating himself to promoting cooperation across divisions of religion, nationality, and class. Like many of his generation, the future Simon envisioned was one of humanism, not tribalism – of modernism, not traditionalism. He paid a high price for his beliefs. Singled out by Nazi propaganda as an exemplar of the link between Jewish finance, left-wing politics, and modern art, Simon was forced into exile in 1933 and stripped of his German citizenship in 1937. When he died in Brazil thirteen years later, he had lost almost everything else: his home and properties, his beloved art collection, his work and livelihood, even his identity and past.

Fig. 1: Portrait of Hugo Simon by Josef Breitenbach, 1930s; Family Archive Hugo Simon.

Fig. 2: Hugo Simon, circa 1907; Hugo Simon Family Archive.

Hugo Simon’s name rarely rates more than a footnote in histories of twentieth-century Germany, although he played an outsize role in the cultural life of the Weimar Republic. Those who research the period are bound to come across him in an impressive array of capacities. His early renown came as a political player, initially as an activist in the Bund Neues Vaterland movement, which defended peace with France during the First World War, and subsequently as Prussian Minister of Finance in the revolutionary cabinet of November 1918, a position he divided with the Social Democrat Albert Südekum (1871–1944) in the power-sharing arrangement between USPD and SPD. When the Independent Socialists withdrew from the government in January 1919, Simon left with them, putting an end to his brief spell in the political limelight. His wife Gertrud Simon, née Oswald (1885–1964) played a crucial role throughout his career. Also born in the province of Posen – in Koschmin (Koźmin Wielkopolski), where their father was a cantor in the synagogue – she and her two sisters all wed prominent figures in socialist circles: Cäcilie Oswald (1882–1951) was married to Kurt Heinig (1886–1956), an SPD member of the Reichstag from 1927 to 1933, and Olga Oswald (1881–1941) to Alexander Bloch, a journalist linked to the USPD.

Fig. 3: Gertrud Simon, Max Liebermann, Albert Einstein, Aristide Maillol, and Renée Sintenis at the Simons’ residence, Drakestraße 3, Berlin-Tiergarten, 15 July 1930; Family Archive Hugo Simon.

The source of Simon’s influence in the 1910s and 1920s was his role as a banker. In 1911, he co-founded his first private bank, Carsch Simon & Co., later succeeded by the firm Bett Simon & Co., founded on 9 November 1922. Both banking houses specialized in the capitalization of industries and urban development projects. Their successive partners sat on the advisory boards of dozens of corporations, extending their influence well beyond finance. Bett Simon & Co. also handled the private accounts of conspicuous figures on the cultural scene, including writers Heinrich Mann (1871–1950), Ernst Toller (1893–1939), and Kurt Tucholsky (1890–1935), theatre director Erwin Piscator (1893–1966), art dealer Paul Cassirer (1871–1926), and communist propagandist Willi Münzenberg (1889–1940). It was his connections on the left of the political spectrum that earned Simon the epithet of the ‘red banker.’

The third arena in which Simon gained prominence was as an art collector. From the 1910s until the 1930s, he amassed a sizeable collection that included most of the artists now associated with German expressionism. The collection was notable for its quality, as well as for its unique attention to contemporary sculpture. Many of the works formerly owned by the Simons are displayed today in major museums throughout the world, including Edvard Munch’s (1863–1944) The Scream (1895). The Simons were closely acquainted with Paul Cassirer, Harry Graf Kessler (1868–1937), Max Liebermann (1847–1935), and Julius Meier-Graefe (1867–1935), among other influential figures in the art world. They became part of a Berlin scene that gravitated towards modern art in the early twentieth century, championing artists such as George Grosz (1893–1959), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938), Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980), Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881–1919), Franz Marc (1880–1916), Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907) and Max Pechstein (1881–1955), among many others. Simon’s passion for art led to his involvement with the National Gallery in Berlin, where he became a member of the acquisitions committee.

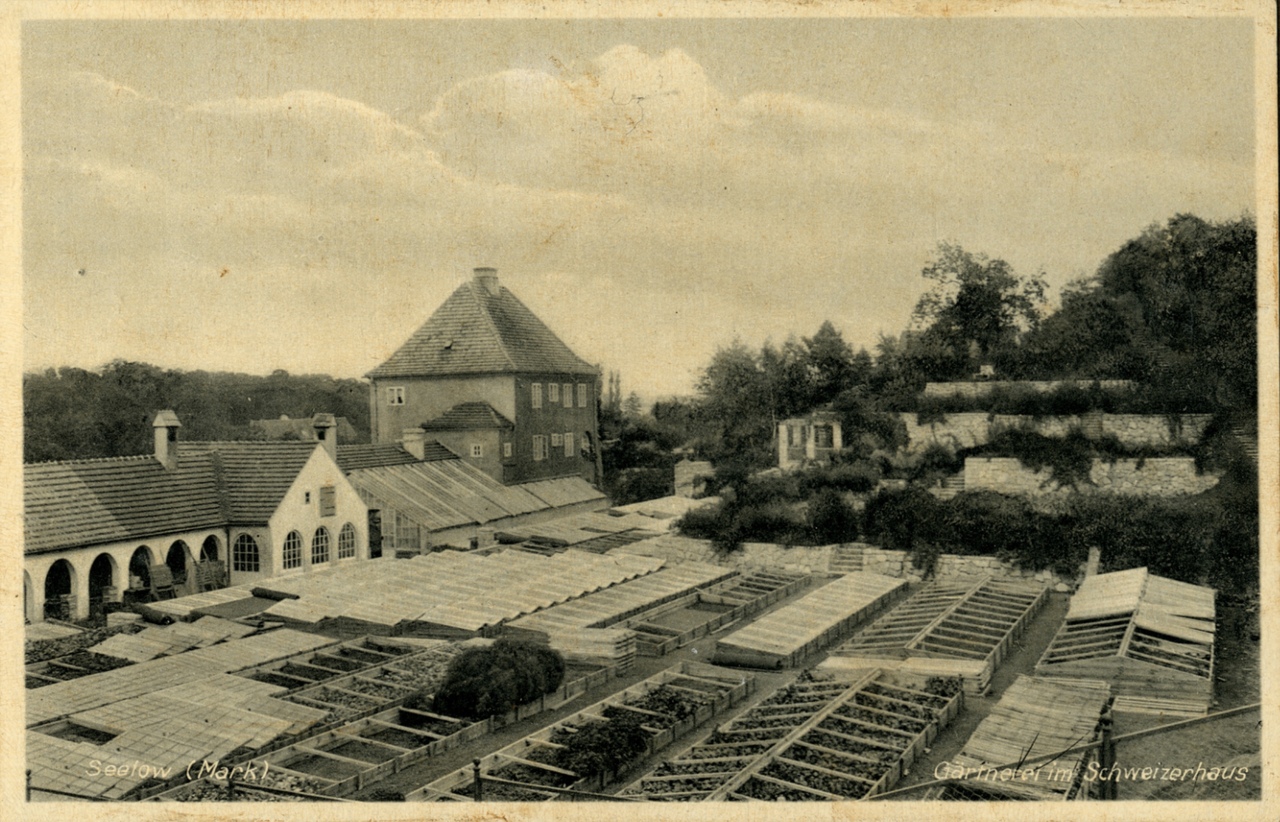

The least known facet of Simon’s multiple activities was as an innovator in agriculture. He took an interest in the subject from a young age and briefly considered studying it before ultimately settling on banking instead. Shortly after his withdrawal from politics in 1919, he acquired a property in the town of Seelow, Brandenburg, which he proceeded to transform into a productive farming estate over the following decade. The principal commercial focus was growing fruit. Employing advanced methods and management and with an eye to the social welfare of its employees, the Schweizerhaus Seelow became a model estate and a regional tourist attraction. It fulfilled Simon’s ambition of creating a private utopia. His experience with commercial agriculture would stand him in good stead in exile.

Fig. 4: Postcard of Schweizerhaus Seelow, a model farming estate established by Hugo Simon, Seelow, Brandenburg, 1920s.

Hugo and Gertrud Simon were among the first wave of emigrants to flee the Nazi onslaught. They left Berlin in March 1933 and made their way to Paris, where they lived for the following seven years. At least 10,000 Jewish refugees from Central Europe settled in the French capital throughout the 1930s. Initially, the couple were able to extract much of their art collection from Germany, as well as substantial financial resources. In October 1933, Simon’s remaining properties were confiscated under a Nazi decree governing enemies of the state. In June 1934, he established a brokerage firm in Paris and began to operate there as a banker, primarily serving the German exile community. His relative prosperity placed him in a unique position, and he soon became active in organizations assisting fellow refugees, including the Comité d’assistance aux réfugiés and the Caisse israëlite des prêts.

As emigration hardened into exile, Simon’s activities grew more overtly political. Alongside the politician Rudolf Breitscheid (1874–1944), the novelist Lion Feuchtwanger (1884–1958), Heinrich Mann, Willi Münzenberg, Ernst Toller, and other members of the so-called Lutetia Circle, he participated in attempts to form a German Volksfront in 1936. He was one of the leading proponents of the Bund Neues Deutschland organization in 1937 and also became a backer of the Pariser Tageszeitung, the major German-language newspaper in exile. In 1938, he was an important lender to the exhibitions Twentieth Century German Art in London and Art Allemand Libre in Paris. Simon’s activism in exile exacerbated the hatred directed towards him by the NSDAP. He was subjected to vitriolic attacks by the Nazi press, culminating in the expulsion of both himself and his wife from the German nationality in October 1937.

In June 1940, as German soldiers marched into Paris, the Simons were spirited away to Montauban. After the installation of the Vichy regime, they fled further south to Marseille to join the throngs seeking to escape occupied France. They remained there for approximately six months, doing the rounds of the consulates and relief agencies, attempting to line up the complex constellation of entry visas, transit visas, passports, and affidavits required to emigrate to the United States. In the end, they were unable to obtain exit visas from France because Simon was wanted by the Gestapo under the infamous ‘surrender on demand’ clause of the 1940 Armistice. With the help of the Marseille-based Emergency Rescue Committee, headed by the journalist Varian Fry (1907–1967), they eventually escaped via clandestine means, using false Czech passports and crossing into Spain on foot. The couple entered Port Bou on 6 February 1941 and, five days later, embarked in Vigo on a ship to Brazil. They likely chose Brazil because it was one of the few destinations still accessible to Jewish refugees at the time, and because their immediate family had preceded them there a month earlier.

Hugo and Gertrud Simon arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 3 March 1941 as refugees under the assumed names Hubert Studenic and Garina Studenicova. They did not speak Portuguese, knew practically no one, and were in desperate financial circumstances. They reencountered their two daughters, son-in-law and grandson, who had arrived a few weeks earlier, bearing false French passports. However, the extended family group had to pretend they were unrelated for fear of exposing their respective identities. Brazil was not then a haven for Jewish refugees. From 1937 onwards, a cordial relationship between the governments in Rio de Janeiro and Berlin led to the curtailment of immigration by groups deemed to be undesirable – essentially Jews and leftists. That situation only changed in August 1942, when the country entered the war on the side of the Allied powers. By then, however, immigration opportunities for Jews had already become extremely limited.

In April 1941, Simon petitioned the American government to unfreeze his bank accounts and allow the couple to obtain passage to the United States in their real names, despite lacking valid travel papers. The request was unsuccessful. Their application to extend their visas and remain in Brazil was denied on 18 April 1941. Three months later, the purported Hubert Studenic received an expulsion order from the immigration authorities, giving him fifteen days to leave the country, which was later overturned on appeal. The couple’s legal status in Brazil remained precarious, however, and they were only granted permanent residence in March 1947. Simon stayed in Rio de Janeiro until April 1942, reencountering old friends and fellow refugees, including the Viennese writer Stefan Zweig (1881–1942) and the journalist Ernst Feder (1881–1964). The latter remained his principal conduit to the outside world during the subsequent years of hiding in plain sight.

Fig. 5: Fazenda Penedo, agricultural estate administered by Hugo Simon during the early 1940s, Penedo, Brazil; Family Archive Hugo Simon.

Unable to leave Brazil, the Simons decided to relocate to the hinterland. They first moved to the rural locality of Penedo, about 180 kilometres west of Rio de Janeiro. The Swiss pharmaceutical company Geigy was seeking to set up an agricultural establishment to produce medicinal plant extracts, which were in short supply due to wartime disruptions in trade. Simon was tasked with getting the estate up and running. A letter to the writer Annette Kolb (1870–1967), dated 20 April 1942, shows that he was enthusiastic about the venture and captivated by Brazil’s lush nature. Letter from Hugo Simon (Hubert Studenic) to Annette Kolb, 20.04.1942. Monacensia im Hildebrandhaus/Münchner Stadtbibliothek, Munich, AK B 254. The new enterprise, Companhia Agrícola Plamed, employed many refugees, including the couple’s son-in-law, the sculptor Wolf Demeter/André Denis (1906–1978) who helped manage the estate. Simon’s period as administrator was cut short by antagonisms with the Swiss owners as well as intrigues involving colleagues who threatened to denounce him to the Brazilian authorities. In January 1943, he prepared his final report for Geigy and left Penedo.

The next stage of this exile within exile was the town of Barbacena, about 280 kilometres north of Rio de Janeiro, in the mountains of Minas Gerais. Hugo and Gertrud Simon remained there for the duration of the war, maintaining minimal contact with the outside world. He turned his attention to rearing silkworms and scraped a meagre living from subsistence farming. Meanwhile, their extended family relocated to the state of Paraná in southern Brazil, intensifying the couple’s isolation. An unlikely friendship blossomed with the French writer Georges Bernanos (1888–1948), who resided in Barbacena for most of the Second World War. That the German-Jewish socialist befriended the ultranationalist, stridently Catholic writer is a testament to Simon’s extraordinary capacity to connect with people and engage with difference.

After the war ended, the couple moved back to Penedo. From 1946 until his death on 4 July 1950, Simon was preoccupied with reestablishing his identity and attempting to reclaim his properties in Europe. Almost all of these initiatives, pursued even before the processes of ‘Wiedergutmachung’ in the late 1950s, were fruitless. In September 1946, thanks in part to letters of support from physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and writer Thomas Mann (1875–1955), both Nobel Prize laureates, Simon managed to recover his real name, but not his nationality. Without a passport, he could not leave Brazil. His attempts to obtain legal status as a stateless person met with frustration. Instead, immigration authorities first demanded that Simon clarify his status as a Czech citizen since he had entered the country as such and later instructed him to apply for Polish nationality, since his birthplace was now a part of Poland. Between 1945 and 1949, there were no German authorities in Brazil whom he could petition. Lost in the shuffle of postwar turmoil, Simon became a prisoner of the land that had given him refuge.

Fig. 6: Portrait of Hugo Simon, circa 1949; Family Archive Hugo Simon.

Over his final years, Simon worked on an autobiographical novel, Seidenraupen, the unfinished manuscript of which is housed today in the German National Library’s Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933–1945 in Frankfurt. His letters from this period testify to an ongoing enchantment with the local landscape, which he viewed through the lens of Goethean philosophy, bearing witness to his enduring connection to German culture. Though he learned Portuguese and even published articles on agriculture in the press, he remained an outsider in Brazil. The couple built a small circle of friends – mostly Europeans, some artists. However, in a letter from September 1946, Simon confided to a correspondent that he was “no longer hungry for people”. Letter from Hugo Simon to Rita Janett, 03.09.1946; Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933-1945, Frankfurt-a.M. Rita Janett correspondence. Whenever possible, they sought to see their extended family, who by then resided in the neighbouring state of São Paulo.

From 1945 onwards, acting through several proxies, Simon initiated claims in France and Switzerland to recover his looted art collection. Through the efforts of the Commission de recupération artistique, established to return works of art and books looted from France by the Nazis during the Occupation, he managed to recover seven works between 1947 and 1948. Over the many decades since, in a multigenerational effort, his heirs have obtained restitution or settlements for a dozen more. However, this still represents only a fraction of the approximately 230 works that once belonged to the collection, for which research is ongoing with the support of the Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste. In recent years, interest in Hugo Simon has grown in Germany, and his biography is scheduled for publication. The Hugo Simon Stiftung was established in 2021, with its seat at the Schweizerhaus Seelow. Remarkably, though, for someone who exercised such great influence in his time, he remains largely forgotten.

Rafael Cardoso, Das Vermächtnis der Seidenraupen. Geschichte einer Familie. Frankfurt: S. Fischer, 2016.

Information about Hugo Simon’s life and legacy provided by the Hugo Simon Foundation: Hugo Simon Stiftung — Homepage

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Prof. Dr. Rafael Cardoso is an art historian and writer, member of the postgraduate faculty in art history at Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Instituto de Artes) and research associate at Freie Universität Berlin (Lateinamerika-Institut). He is the author of many books, essays and scholarly articles on the history of art and design in Brazil, 19th and 20th centuries. Over the past decade and a half, he has also delved deeply into the history of his own family’s exile and refuge, particularly that of his great-grandfather Hugo Simon. On that subject, he published the historical novel O Remanescente (Companhia das Letras, 2016), translated into German and Dutch, as well as co-editing the volume Hugo Simon in Berlin (Hentrich & Hentrich, 2018) and contributing essays and interviews to various sources on exile studies. He is chair of the board of the Hugo Simon Stiftung, headquartered in Seelow, Brandenburg, on the estate formerly owned by his great-grandfather.

Rafael Cardoso, Hugo Simon (1880–1950), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-22> [February 08, 2026].