The island of Cyprus is located in the northeastern part of the Mediterranean Sea, in proximity to the coasts of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean after Sicily and Sardinia. Its geographic location and physical features have influenced the populations and cultures that inhabited it throughout history. The unique geographic position attracted forces and powers during all historical periods, and the physical characteristics affected the distribution of the population, the forms of urban and rural settlements, and the potential of resources and the island's economy over generations.

In a general overview of Cyprus’s place in the historical fabric of German-speaking Jewry and the island, it should be noted that this was ultimately a brief historical episode, incomparable to other communities of the German-Jewish diaspora across the world. The historical connection between German-speaking Jews and Cyprus was coincidental and temporary, and no German-Jewish ‘exile’ community was established there. Nevertheless, Cyprus has a place here due to the unique circumstances under which German-speaking Jews arrived on the island. The formation of a tiny community during the Second World War was the result of refugees from Nazi Germany who found warm and safe haven there. It is estimated that between 1939 and 1945 around a few hundred German-speaking refugees arrived in Cyprus. They passed mostly through the island, which became a temporary place of refuge, while other individual German-speaking Jews took part in attempts to find settlement solutions and absorption options for Jews on their way to Mandatory Palestine or even as an alternative to it. Apparently, even Theodor Herzl (1860–1904), the visionary of the Jewish state, saw Cyprus as an alternative destination and 'temporary refuge' until the vision of establishing a national home in the land itself could be realized.

Cyprus’s history stretches back thousands of years, as part of the fabric of Hellenistic culture and struggles for control over the Mediterranean since antiquity. Throughout most of the island’s history, Cyprus was not an independent entity, but rather a part of larger polities and kingdoms that saw it as an important strategic foothold. Importantly, the island’s population maintains a continuity of identity with the ancient Mycenaean and later Hellenistic cultures, despite ancient settlement by migrants, traders, and mariners from the Levant, Assyria, and Egypt as well. Its population intermixed with people of diverse origins over the years, but its identity gradually coalesced as part of Greek island culture despite the great physical distance from Greece itself and proximity to the Levantine coasts. Later, the island attracted Muslim settlers as well. During Ottoman rule, a third of the inhabitants were Muslim. Eventually, the ratio of Greek Christians to Turkish Muslims stabilized at a similar magnitude. The island’s population dwindled to around 80,000 under Ottoman conquest in 1571, growing back to 181,000 by 1881.

The population of Cyprus in 2024 is estimated at 1.4 million inhabitants. The vast majority, around 75 percent, are Christians, predominantly Greek Orthodox, while Muslims constitute around 24 percent of the population. The estimated Jewish population on the island is around 10,000, comprising a small minority of established Cypriot Jewish families and a larger proportion of Israeli nationals who have temporarily relocated to Cyprus over the past decade. The identity of the Cypriot population was thus culturally and religiously shaped through the medieval and early modern periods, forming the roots of its distinct identity compared to other Greek islands.

Throughout the island’s long history, Jewish migrations and presence intersected with various key events and settlement processes. Cyprus was part of the Phoenician and Hellenistic spheres in which Jews traveled and settled, and some scholars attribute inscriptions from the Persian period (sixth century BC to fourth century) to an established Jewish presence and influence on the island. During Roman times, a more significant Jewish community was already likely benefiting from trade ties with Judea. Between 115–117 CE, it appears that the Cypriot Jewish community took part in the ‘Diaspora Revolt’ of Jews across the Mediterranean, as it was harshly suppressed, and Jews were subsequently banned from settling on the island. A sporadic Jewish presence left little lasting historical imprint until 1878, when the island passed to British rule. The island’s colonial governors generally encouraged immigration and minority settlement to bolster the economy and reduce administration costs. Cyprus’s proximity to Palestine was an important factor for pre-Zionist and Zionist settlement groups considering the island as a springboard to Palestine or ‘interim refuge’ en route.

The first attempt at modern-era agricultural settlement was made by chance, when the British missionary society The Syrian Colonization Fund sent a group of around 200 Jewish settlers to the Latakia area of Syria but due to unforeseen circumstances found refuge in Larnaca, where British officials assisted them in finding a plot near the village of Kouklia in the Paphos district. The settlers persevered for only a year and a half, facing adaptation difficulties, hostility from neighbors, and a lack of sufficient support from the missionary society.

Fig. 1: Tombstone of a Jewish settler in Kouklia; in private possession of the author.

In 1892, a proto-Zionist society named Ahavat Zion (The Love of Zion), established by a group of Eastern European Jews from London, purchased a sizable tract of land on the road from Larnaca to Nicosia, attempting to settle a number of member families there from 1897, joined by some graduates of the Mikveh Israel agricultural school in Ottoman Palestine. This effort also failed, but the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA), founded by the German-born philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch (1831–1896), which had backed the land purchase, preferred to try establishing a Jewish agricultural settlement bloc similar to their contemporaneous project in Lower Galilee in Palestine. The large village of Margo was established as a kind of ‘mother settlement’, from which families of Eastern European origin later branched out to found two tiny additional moshavot: Cholmakchi and Kouklia/Famagusta.

The JCA poured significant funds into maintaining the settlements. At their peak in 1915, these settlements had around 60 families and 150 residents in total. However, it was the very proximity to Palestine that had initially attracted settlement attempts, when settling there itself faced difficulties under Ottoman rule – this same proximity ultimately contributed to the agricultural settlements’ demise. As the gates to Palestine opened under the British Mandate in 1922, most families gradually left to settle in towns and rural communities within Palestine itself. In 1928, the JCA decided to halt support for the remaining settlers and sell the lands. A few Jewish farmers continued on portions of the lands, but by the time of Cypriot independence, no Jewish agriculturalists remained.

Fig. 2: The Cyprus Palestine Plantations Company Ltd. was established in 1933 by a group of investors led by the Zionist Simcha Ambache (1892–1973) in Limassol, grandfather of Israeli President Isaac Herzog (*1960). It was only sold to local Cypriot owners in the 1970s, though it operates under a different name today. Prospectus printed in Tel Aviv in 1935; courtesy of the Bank of Cyprus Historical Archive.

In the 1930s, agricultural entrepreneurs from Mandatory Palestine itself came to Cyprus, establishing large-scale citrus plantations around Limassol and Kouklia/Famagusta, as well as smaller farms in other areas. Among them was the husband of Elsie Slonim (1917–2021), who grew up near Vienna and decided to follow her spouse to Cyprus in 1939. Most were based on growing various citrus crops, taking advantage of British Dominion regulations, since Cyprus became a Crown Colony in 1925, to market the fruits at lower prices in England. Some companies transformed the Cypriot landscape, bringing prosperity and ample employment to the local population. They too operated until the early 1960s. One company was founded in 1933 by German Jews already living in Palestine itself, headed by Dr. Wilhelm-Zeev Brünn (1884–1949), a renowned doctor and health expert who was educated in Berlin, and the founder of Meged citrus village near Pardes Hanna. Brünn’s Cyprus Farming Company Ltd. planted thousands of dunams of citrus at the Kouklia/Famagusta settlement site with the object of providing suitable land for the agricultural establishment of middle-class Jews from Nazi Germany, but the Second World War cut short this planting enterprise.

During the first half of the twentieth century, groups of German-speaking Jews primarily viewed Cyprus as a site of refuge or a transitional territory en route to Palestine. In the 1930s, proposals were occasionally put forward to relocate Jews from Nazi Germany to the island, utilizing lands already under Jewish ownership. A fascinating episode in German-Jewish engagement with Cyprus occurred at the turn of the twentieth century, initiated by Davis Trietsch, a German-born Zionist, who researched Cyprus and found it a suitable temporary refuge for the Jewish people as an alternative to Palestine. It should be noted that the entry of Jews, particularly those of Russian origin, into Ottoman Palestine was dependent on the will of the rulers in Constantinople. There were certain periods during which immigration was completely prohibited, such as in the years 1883–1887, making it difficult for Jews to view the Land of Israel as a migration destination when tens of thousands of them left Eastern Europe in search of a new home where they could live in freedom and equality.

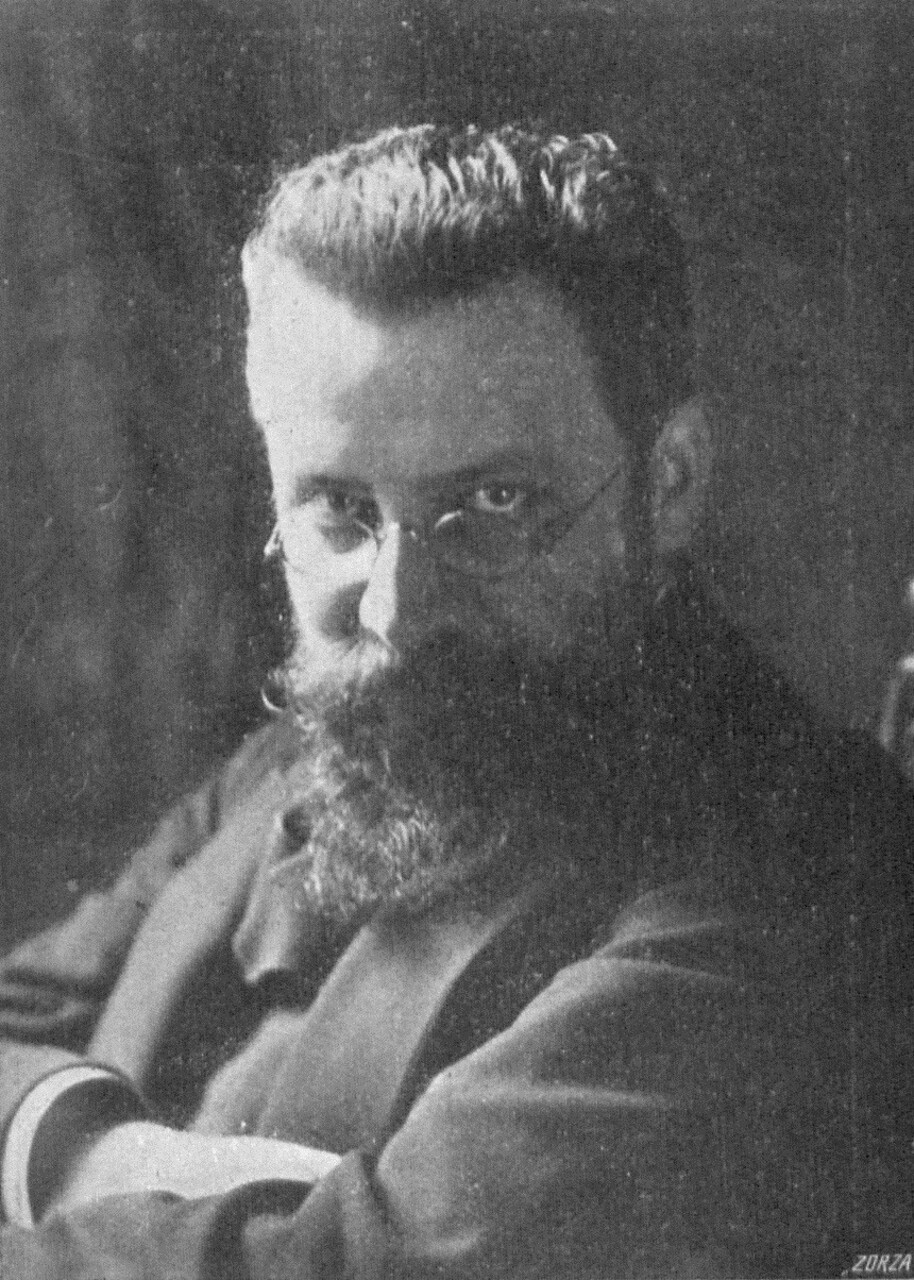

Fig. 3: Portrait of Davis Trietsch for his article “Odpowiedź niezadowolonego”, in: Leon Reich (ed.), Almanach Żydowski, Lwów 1910, n. p., digitized by the Biblioteka Cyfrowa Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

Trietsch was a prominent activist and entrepreneur, specializing in immigration and settlement issues alongside other general Zionist causes. He co-founded the renowned Ost und West monthly journal in 1901 and a year later the Palästina periodical, which became the first German-Jewish journal specializing in Palestine and possible Zionist activity in this land. Other publications by Trietsch, like the Palästina Handbuch, saw many editions and served as important sources of knowledge about the Land of Israel. In 1899, he published a pamphlet titled The Future of Cyprus linking the island’s future to England’s imperial interests, the Zionist movement, and the island’s own inhabitants. At the Third Zionist Congress that same year, Trietsch was permitted to present his idea of Cyprus as a ‘temporary refuge’ for the Jewish people, but was not allowed to finish his speech, and the idea ostensibly faded. In practice, however, Theodor Herzl himself became interested in it in 1902, though the ‘Uganda proposal’ famously gained more traction instead.

Trietsch’s pursuit of his plan was focused not on German Jewry but on Eastern European Jews seeking to emigrate from their homelands. His efforts were conducted concurrently among Galician Jews within Germany itself – where he established a support committee comprised of prominent figures such as the Zionist Otto Warburg (1859–1938) and Willy Bambus (1862–1904) – as well as in negotiations with the High Commissioner of Cyprus and the British Colonial Office. In early 1900, Trietsch sojourned in Cyprus, persuading an initial group of Jews from Borysław, Galicia, to immigrate to the island, promising them employment and living conditions conducive to a Jewish settlement. He secured several job opportunities for them and presented a development plan to the island’s governor that could potentially employ no fewer than a thousand families. Trietsch’s attempts failed on all fronts – the job opportunities were limited, the settlement conditions were poor, and all twelve families returned home demoralized.

Undeterred, Trietsch persevered. When ideas for finding a temporary alternative to Palestine resurged, especially after Adolf Hitler’s (1889–1945) rise to power in 1933, he actively advocated for Jewish immigration to Cyprus. Until his death in 1935, he campaigned for settling Jews in Cyprus, given that it was much closer to Palestine than other places of refuge such as Argentina or the United States.

During the 1930s, Cyprus occasionally emerged as a potential sanctuary for Jews emigrating from Nazi Germany. As their situation deteriorated, Cyprus increasingly appeared as a viable place of refuge. Requests for permits to settle down on the island for associations and individuals were directed to London, some even garnering support from Members of Parliament. Indeed, a number of families found their way to Cypriot coastal cities, where they secured partial employment in various professions. Many refugees who predominantly originated from Germany, followed by Austria and Czechoslovakia, came from professional and commercial occupations. In Cyprus, they could not easily sell their labor on the employment market and therefore had difficulty fitting into the professional and occupational field. Some refugees lived off the money they had brought with them, while others set up small businesses and opened their own clinics, grocery stores, or pensions for Jewish tourists. Although an identified and organized German-speaking refugee community did not develop in Cyprus as it did in other places, some communal structures were established through these businesses.

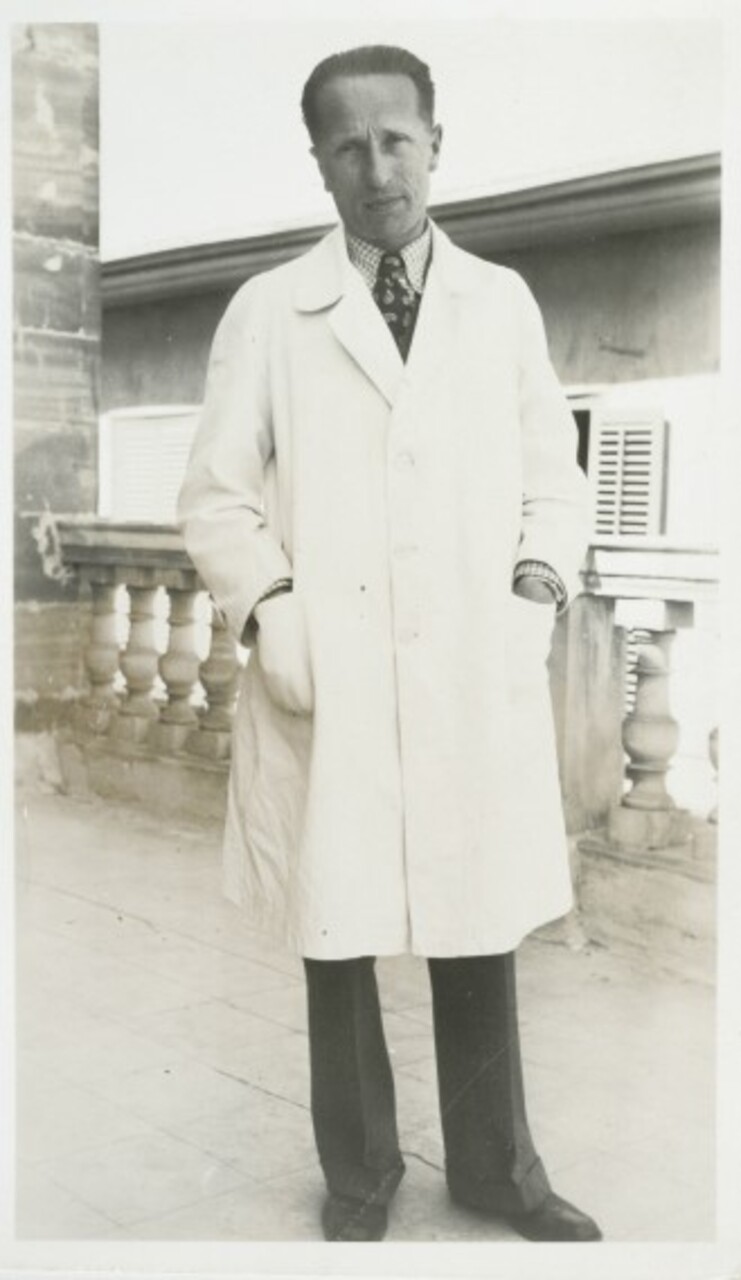

Fig. 4: Erich Simenauer (1901–1988) from Berlin in a private clinic in Nicosia, March 1937. Simenauer, who was a doctor, emigrated to Cyprus in the early summer of 1933 and took British citizenship in 1939 after the German consul refused to renew his passport; Jewish Museum Berlin, FOT 90/6/2, donated by Agnes Wergin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

The unique historical circumstances of the mid-1930s positioned Cyprus as a potential rescue destination: the pressure to leave Nazi Germany intensified, Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine itself provoked severe and violent opposition from the Arab population, and in Cyprus, the British administration saw a need to encourage settlement by new, loyal elements as a countermeasure to the awakening Cypriot nationalism. British colonial rulers also hoped to improve the island’s economy by allowing professionals with various technical expertise to settle there.

One significant expression of this approach was integrated into the initiative of the already mentioned Cyprus Farming Company Ltd., headed by Wilhelm-Zeev Brünn. Brünn who had settled in Hadera, Palestine, noted in 1934 that the idea for Jewish agricultural development in Cyprus not only did not contradict the central Zionist goal of immigration to the Land of Israel, but that it would allow for the rescue of German Jews threatened by the ‘catastrophe,’ not all of whom could reach Palestine. He believed a figure of 10,000 Jews could be absorbed in Cyprus at the time, providing some relief to the distress of German Jews.

Brünn invited the former president of the Zionist Organization, Otto Warburg, to tour the estate acquired by the company in the fertile plain of Eastern Cyprus. Warburg indeed visited Kouklia on his way to Palestine, expressing a positive opinion about the potential success of the planned citrus plantations on the island. The head of the Jewish Agency in Mandatory Palestine, the German-born Zionist Arthur Ruppin (1876–1943), also visited the area and documented his impressions in an official report from 1935. As stated by Ruppin, around 60-80 Jews from Germany lived on the island, mainly engaged in citrus planting. News of the Cyprus plan spread in the Palestinian press and among German Jews. Ruppin noted in his diary that the locals and the government in Cyprus did not object to the absorption of individual Jews but would not agree to mass immigration, and in general, Palestine was preferable to Cyprus as a destination for emigration from Nazi Germany, although Cyprus was certainly preferable to Brazil or Uruguay due to its geographical location.

It is worth noting that all the proposals for Jewish immigration to Cyprus, like Trietsch’s plans, were met with opposition on several levels: first and foremost was the Greek Cypriot elite, who opposed these intentions for various reasons, some clearly antisemitic, some as a nationalist response against British colonial rule. Among the leaders of the Jewish Agency, there was also no enthusiasm for the very idea of Jewish immigration to destinations other than Palestine and for directing investments away from the Zionist project. Finally, the Colonial Office and the British government did not see any of this as a step that would make it easier for them to deal with the Cyprus issue.

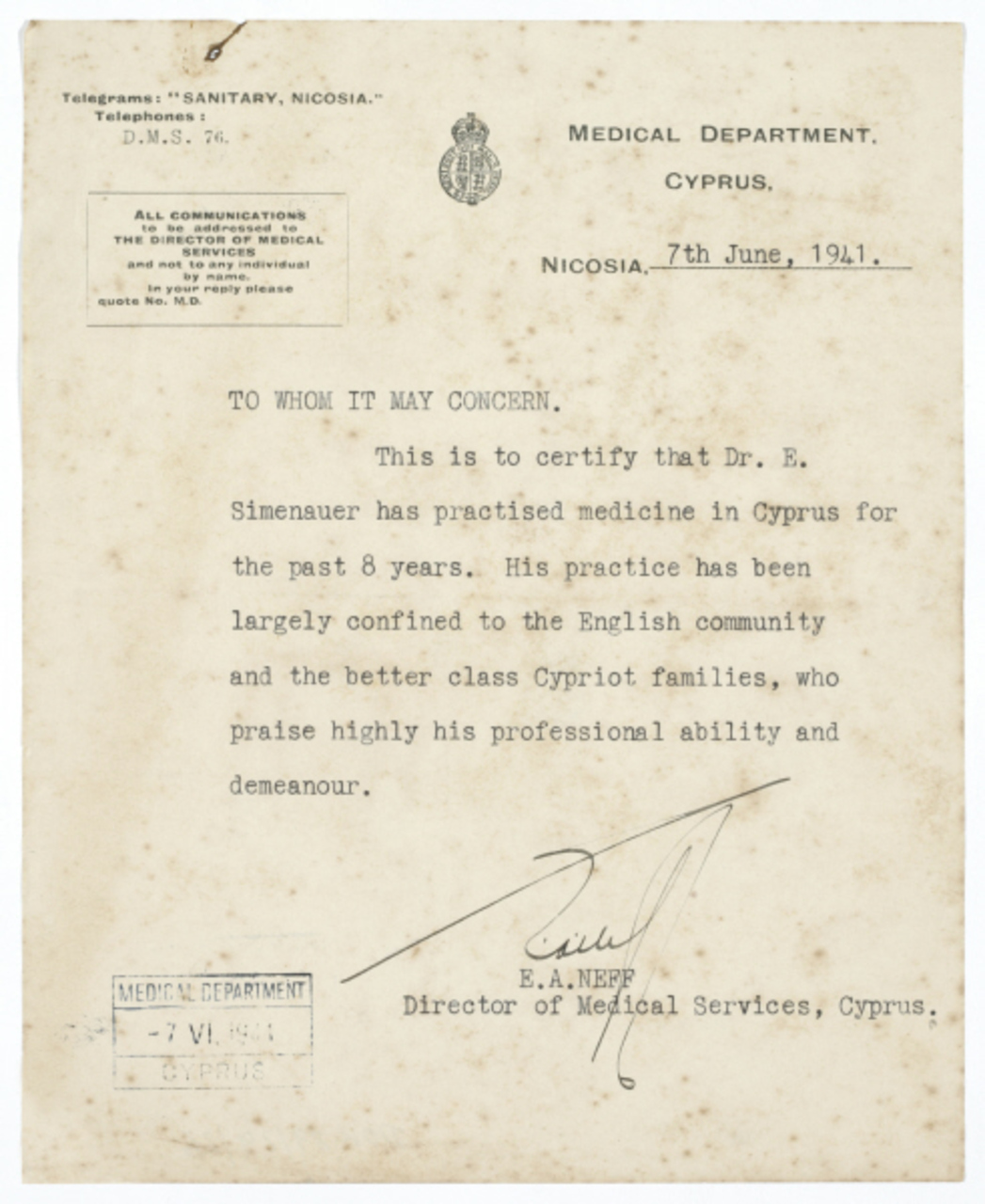

On the eve of the Second World War, there were several dozen families of Jews of German and Austrian origin on the island, scattered in several coastal cities and engaged in various fields of employment. They were joined by war refugees who arrived on the island under multiple circumstances and were dispersed in several mountainous villages. Almost all of them were eventually included in a list of 426 refugees from Central Europe who were transferred by British officials from Cyprus in June 1941 to various destinations within their spheres of influence, including Egypt, the British protectorate of Nyasaland (Malawi), and Tanganyika (Tanzania).

Fig. 5: Certificate of Simenauer’s medical activity in Cyprus, June 1941. Together with other Jewish refugees, Simenauer was shortly after forcibly evacuated, as an invasion by German troops was feared after the capture of Crete. Simenauer and his wife came to Tanganyika in East Africa, a British mandate territory; Jewish Museum Berlin, DOK 89/29/26, donated by Agnes Wergin, photo: Jens Ziehe.

The historical episode most familiar to the general public about Jews in Cyprus is the case of the detention camps established there by Britain as part of its policy to halt what it deemed as illegal immigration to Palestine. Starting in 1939, the British imposed restrictions. The Hebrew Yishuv (settlement) and the Jewish Agency for Palestine began a struggle that lasted about ten years to bring Jews beyond the quota established by the Mandate government, which classified them as illegal immigrants. The struggle was called ‘Ha'apala’ (illegal immigration), during which thousands of Jews were brought to Palestine by ships and land routes, while the British fought against this effort by establishing detention camps throughout Palestine. In the summer of 1946, following the intensification of the rebellion against the British and the bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, the British began establishing deportation camps in Cyprus, to which immigrants caught off the shores of Palestine were transported via deportation ships.

During 1946–1949, around 52,000 detainees passed through these camps for periods of several months each, and some 2,200 babies were born in the military hospital in Nicosia. The camps were concentrated in proximity to Famagusta and Larnaca, and became sites of collective organization and robust Zionist activities behind the bars and fences of British guard posts. Communal life developed within them, with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) operating educational, cultural, and sports systems. Clandestinely, various political parties were also active in these camps, and training sessions for the Zionist paramilitary Haganah organization were conducted through emissaries from Mandatory Palestine. Many of the internees in these camps were Jews of German and Central European origin. However, they cannot be considered as a formation of a German-Jewish diasporic post in Cyprus. The camps essentially functioned as temporary holding areas for refugees and immigrants attempting to reach Palestine and the newly established State of Israel, rather than as permanent settlements. While they developed some attributes of community life, their residents were in a state of transience, awaiting the opportunity to complete their journey to the Land of Israel.

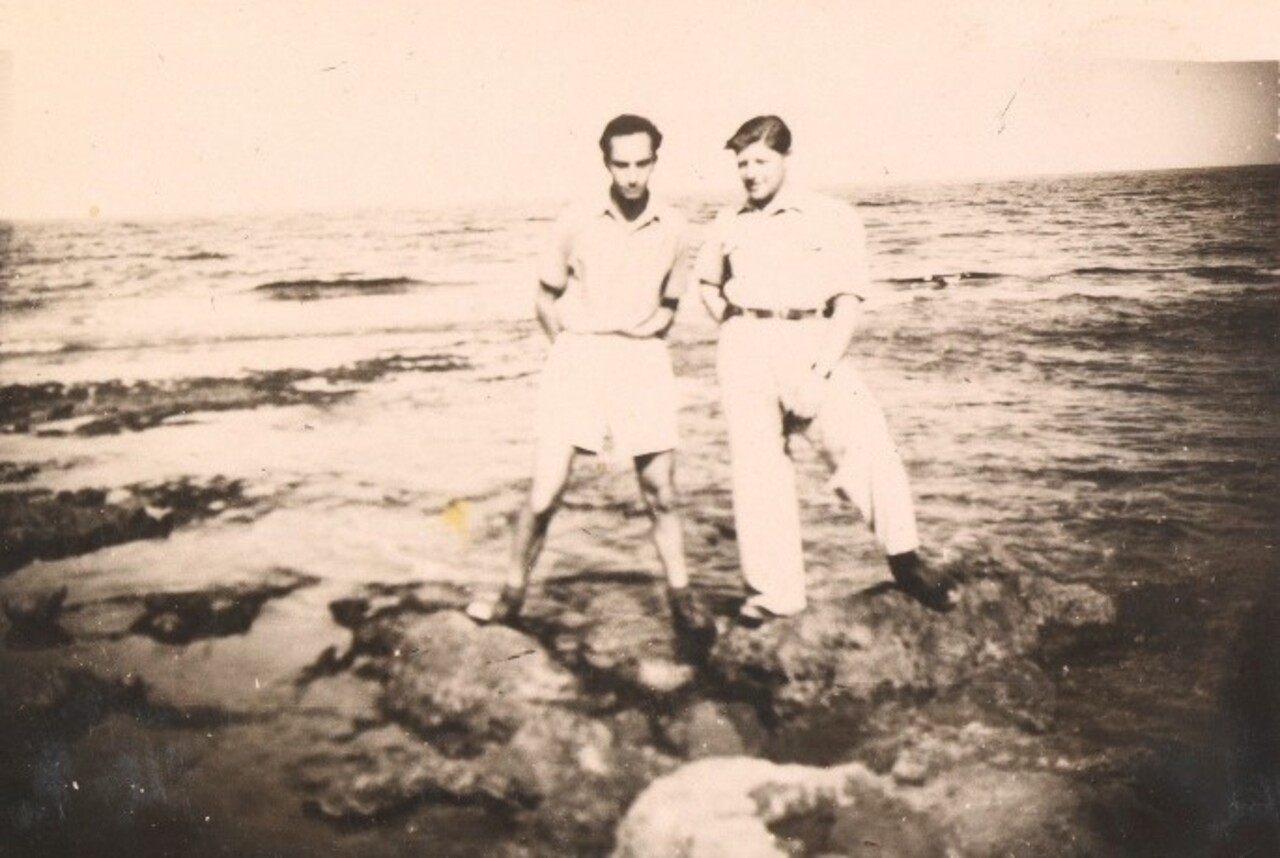

Fig. 6: Walter Frankenstein (1924–2025) on the left, with a man on the coast of Cyprus, around 1947. Frankenstein was born in Flatow (Złotów) and was later interned in a camp near Famagusta from November 1946 to May/June 1947. He then lived in Israel before emigrating to Sweden with his family in 1956; Jewish Museum Berlin, 2010/164/20/002, donation from Leonie and Walter Frankenstein.

After the Second World War, some German-speaking Jews who once found refuge in Mandatory Palestine traveled to Cyprus which emerged from the early stages of Nazi persecution as a transit point and sanctuary for hundreds of Jewish refugees. Max Marcus (1892–1983), once a Berlin-based doctor who lived in Israel, was one of them. He advised patients on Cyprus, where he had close friends, and operated on some of them later in Israel.

Today, there is no German-speaking Jewish community present on the island. After the evacuation in the summer of 1941, only a few returned eventually. Among those was Elsie Slonim (1917–2021), who left Israel for Cyprus in the 1950s. She lived next to the buffer zone in northern Nicosia, which cuts through the city since the Turkish invasion in 1974, with her husband, who ran a renowned citrus plantation near Limassol. After he died in 2007, Slonim stayed in the Turkish Cypriot army camp, supported by local soldiers and the staff of the Austrian embassy, who felt obliged to look after the elderly German-speaking lady with roots in Austria.

The historic Cyprus Collection of the JDC, which contains a wide array of materials that shed light on the lives of deportees to Cyprus: https://archives.jdc.org/jdc-cyprus-collection-available-online/

The Walter and Leonie Frankenstein Collection at the Jewish Museum Berlin contains more than 1,100 objects, including photographs, albums, and writings, documenting Walter Frankenstein’s life from early childhood through retirement: https://www.jmberlin.de/en/topic-walter-frankenstein

Cyprus Virtual Jewish History Tour by the Jewish Virtual Library. A Project of AICE: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/cyprus-virtual-jewish-history-tour

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Prof. Yossi Ben-Artzi is a member of the Department of Israel Studies at the University of Haifa, specializing in the historical geography of Israel in modern times, the history of the city of Haifa, and heritage preservation. He served as Chairman of the Department of Israel Studies, Dean of the Faculty of Humanities, and Rector of the University of Haifa. Ben-Artzi has extensively dealt with the history of Cyprus and its Jewish presence in modern times. He published nine authored books, eight edited books, and numerous articles in refereed journals. Among his publications is the book A Near-Distant Island. Jewish Settlements on Cyprus, 1883–1939 [in Hebrew, Ramat Gan, 2015]. Ben-Artzi is a co-founder of the European–Mediterranean University (EMUNI), established in 2008. Alongside his academic career, he led several civilian movements and organizations focused on environmental issues.

Yossi Ben-Artzi, Cyprus: A Temporary Refuge for German-Speaking Jews, in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-21> [February 28, 2026].