In July 1938, American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945) convened an international conference in the French town of Évian-les-Bains to facilitate the massive resettlement needs of Jewish refugees following Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria. While representatives of the thirty-two countries in attendance expressed concern for the refugees’ plight, the Caribbean nations of the Dominican Republic and the Republic of Haiti seriously considered welcoming these exiles. The Haitian government planned to create a settlement area for 50,000 Jews to develop their own agriculture and industry. However, strong opposition from the American government and support for the Dominican plan eventually led to only 250-300 Jewish refugees, mainly of German and Austrian background, reaching Haiti.

The historical connection between German-speaking Jews and Haiti was temporary, and no German-Jewish ‘exile’ community was established there. Nevertheless, Haiti holds a place in the history of the German-Jewish diaspora as a haven where several German-speaking Jews found refuge.

The Haitian Government was invited to the Évian conference. President Sténio Vincent (1874–1959) was represented by Léon Robert Thébaud (1894–?), a commercial attaché at the Haitian embassy in Paris with the rank of Minister. Invoking the egalitarian ideals of the 1804 Haitian Revolution, which ended the institution of slavery and imposed a universal political philosophy grounded in human rights, Thébaud voiced his government’s intention to accept some refugees. While the methods of acceptance needed to be defined, certain types of refugees would be more advantageous to the nation’s development. Preference would be given to agricultural experts and to persons with technical qualifications in small industries, bringing working capital with them and likely to settle in the country.

A few months following the conference, President Vincent agreed to hear a proposal to settle 5,000 Jews on Haitian territory, where the population was estimated at around 3.2 million. The initiative, which would be primarily funded by the French Jewish organization Rothschild-Swiss Seligman, aimed to create a self-contained settlement area where the refugees could develop their own agriculture and industry in the form of a corporate establishment, with some shares distributed to the Haitian government in return for the land. The Môle-Saint-Nicolas and Gonâve Island, on the northwestern coast of the country, were the locations chosen for the project.

Fig. 1: Portrait of Sténio Vincent, former mayor of the capital city of Port-au-Prince, who was elected the twenty-eighth president of Haiti in 1930, undated; Source: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Roosevelt’s government quickly rejected this plan. Since the beginning of the Second World War in September 1939, the United States has sought to strengthen the network of military and naval bases it maintained in the Môle-Saint-Nicolas region and on the island of Gonâve. According to the American government’s position, the presence of a group of Jewish people, including potential spies for the Nazi regime, posed a threat to American national security and could not be tolerated in a maritime surveillance zone.

The correspondence between Undersecretary of State, Sumner Welles (1892–1961), and U.S. Minister to Haiti, Ferdinand Mayer (1887–1986), makes it clear, however, that the main objections to the project centered on a supposed incompatibility between Haitians and Jews. For them, differences in race, standard of living, culture, and customs between European Jews and the Haitian people would inevitably create serious frictions, and the plan would never have a successful outcome. In the end, only a fraction of the prospective immigrants were able to reach Haiti because of the US government’s preference for the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA) project, led by James N. Rosenberg (1874–1970) as president and Joseph A. Rosen (1877–1949) as vice-president, on the other side of the island where General Rafael Trujillo (1891–1961) had established a dictatorship. Initially aimed to take in up to 100,000 Jewish refugees, this plan provided protection for fewer than 1,000 persons in need. The Jewish settlement in the town of Sosúa, in the northern part of the Dominican Republic, was a public relations move to cast Trujillo as a humanitarian and supportive of Pan-American solidarity, especially after the 1937 massacre of thousands of Haitians along the border. At the same time, he saw the settlement as a way to ‘whiten’ the Dominican population as part of his state modernization plan, which sought to exclude Haitian presence.

Jewish presence in Haiti predates the arrival of refugees during the Second World War by several centuries. Their history in the area goes back to the 1492 Alhambra Decree, which ordered the expulsion of all Jews from Spain and Portugal. In 1654, during Portugal’s reconquest of Brazil, the Jews of the Dutch colony New Holland were expelled from the country, leading to a larger influx of Jews to Haiti. Many were employed by the French sugarcane plantations and helped develop the industry. Haiti, the western part of the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, was initially colonized by the Spanish Empire. By the end of the seventeenth century, it had passed into French control. Sugarcane plantations worked by enslaved Africans made it France’s wealthiest colony. Following the 1804 Revolution, Haiti became the first sovereign state in the Caribbean to officially abolish slavery.

Multiple studies indicate the presence of a Jewish community in Saint-Domingue during the colonial era. Archaeological findings, for instance, uncovered a crypto-Jewish synagogue in the commune of Jérémie and a Jewish cemetery in Cap-Haïtien dating back to the 1804 Revolution. Lists of traders or planters with Jewish surnames, and geographical maps from the eighteenth century showing towns named Anse-à-Juif and Pointe-à-Juif, were discovered as well. Poles, possibly including Jews, settled in Haiti’s regions of Casale, Fonds-des-Blancs, and Jacmel Valley. As defectors from Napoleon’s 1802-1803 expedition, they were welcomed by Haitian Emperor Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758–1806). The 1805 Constitution gave these Poles Haitian citizenship and exempted them from the rules applied to other whites. In the 1830s, more Polish Jews fled to Haiti, escaping Russian occupation and anti-Jewish violence. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Jewish families from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and Morocco arrived in Haiti through the Arab migration. They were descendants of Sephardic Jews who fled Spain after the implementation of the Alhambra Decree and sought refuge in the Ottoman Empire. Locally, they were all called ‘Syrian.’

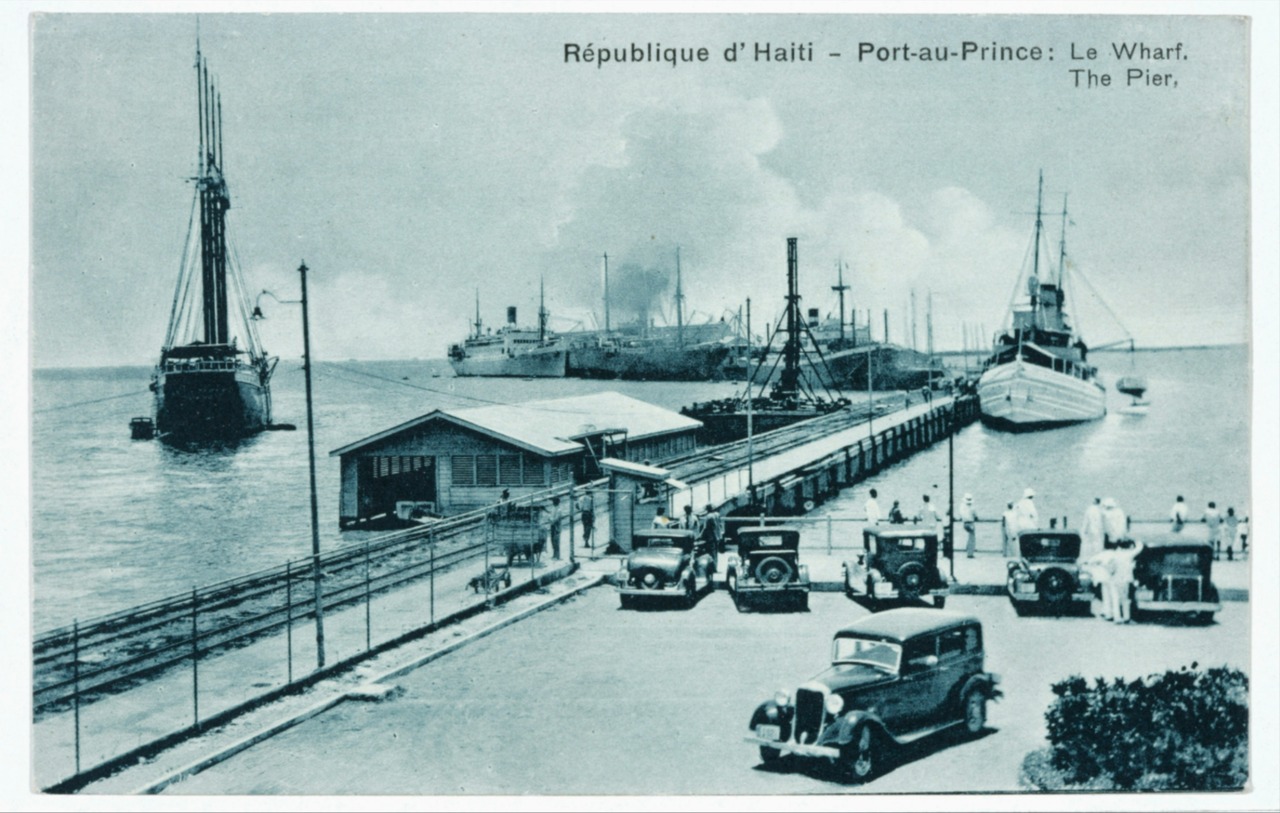

Fig. 2: Historical postcard: View of ships at the pier of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 1920s. Cardboard, 9 x 14 cm; Jewish Museum Berlin, inv. no. 2006/68/2, photo by Jens Ziehe.

The nineteenth century saw violent internal power struggles, poverty, and political instability in Haiti. From 1915 until 1934, the United States maintained direct control over the country, deploying Marines to expand its naval reach in the Caribbean. This period was marked by violent repression, forced labor, and American oversight of Haiti’s finances, which deeply disrupted the country’s economic and social fabric. Under President Vincent, known for his criticism of U.S. paternalism, Haiti’s immigration policy was relatively liberal. During the Second World War, the first refugees arrived in Haiti in 1938, prior to Nazi Germany’s takeover of Austria. Although the Caribbean was rarely the first choice for Europe’s millions of refugees, the region served as a harbor for many exiles. Aruba, British Guiana (present-day Guyana), Cuba, Curaçao, French Guiana, Puerto-Rico, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago were among the Caribbean countries that took in a significant number of refugees. Other European Caribbean colonies, such as Barbados, British Honduras (present-day Belize) on the Central American coast, the Bahamas, and French Guiana, also granted them refuge, albeit in small numbers. Because statistics do not specify whether non-Jewish family members or deported Spanish Civil War prisoners were included, estimates are imprecise, and it has been approximated that between 24,000 and 28,000 refugees arrived in the Caribbean. Within this context, while Haiti’s contribution to Jewish humanitarian aid was small, it should not be dismissed as lip service. The action taken by the Haitian government was twofold: it granted refugee status and Haitian nationality.

Refugees were able to settle in the country because of the law of 3 March 1937 pertaining to the stay of foreigners. According to this law, a foreigner had to prove that he or she possessed 500 gourdes, Haiti’s national currency, and 1,500 gourdes if accompanied by family. Article 4 of the same law ordered that, following a fifteen-day stay, the foreigner was obligated to seek a one-year residence permit from the Interior Secretary’s office for 10 gourdes. The decree-law of 30 October 1940 raised the cost of obtaining a residence permit from 500 to 1,000 gourdes for single foreigners and from 1,500 gourdes to 1,500 dollars for those with families. Working required special permits, which were both expensive, at 50 dollars, and difficult to obtain.

To ensure the effectiveness of operations on the ground, the relief organization American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), based in New York City, created a local branch, the Joint Relief Committee of Haiti (JRC), in October 1939 in Port-au-Prince, presided by Richard Schachne (1884–1969), himself a refugee. A 54-year-old machinery exporter from Hamburg, Schachne fled Nazi Germany with his wife and two children. In 1939, he registered with the American consul in Port-au-Prince under the German quota. On 1 April 1941, he was allowed entry into the United States and was succeeded by Dr. L. Prinz (?–?) as director of the JRC.

Fig. 3: Refugees, among them Erich and Herta Meinberg from Germany, on the deck of a ship headed for Haiti, 1939; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eva Aviad.

Although local ‘Syrian Jews’ were willing to assist financially in the Committee’s initiatives, they did not want to participate openly in the logistics of the settlement efforts. JDC employees Manuel Siegel (?–?) and Robert Pilpel (1905–1987) believed that the active involvement of the local Jewish community in the Committee would be met with disapproval not only from the Haitian government but also from the American Council. By June 1940, the JRC had received about 200 refugees, mainly of Austrian and German national backgrounds, as well as a few Romanians, Czechs, and Poles. One of the main functions of the Committee was to meet the needs of refugees who had little or no financial means.

The JRC divided them into three categories: those who were able to support themselves financially, those who earned a living, and those who were financially dependent. There were twenty-one families in the group that were financially self-sufficient, some of which had high standards of living. About twenty families made up those who found work or invested their money in productive enterprises. They worked primarily in trade and industry, such as wood carving, farming, sisal product manufacturing and export, dressmaking, or bookkeeping. The last group, comprising twenty-seven families, received monthly relief funds from the JRC according to the size of their household. The difficulty of finding work, due to a lack of opportunities, the work permit fees, and restrictive Haitian laws governing entry into local industries, made this final group of people rely on the Committee for the duration of their stay in Haiti, driving some of them to work illegally.

Though there was no official Jewish neighborhood, people of similar backgrounds and means tended to congregate together. Most of them paid 15 to 20 dollars per month for housing in the capital, Port-au-Prince, or its surrounding suburbs. Participating in group activities required special permission from the government. For instance, under the Committee’s auspices, small English and French classes or religious gatherings in private homes during major religious holidays such as Passover were organized. Few refugees integrated into local society, and even fewer intermarried with Haitians because exogamy was frowned upon among them, though this was less of an issue for those who were better off financially.

Refugees regarded their time on the island as transitory due to their unfavorable perception of the country. Many missed the cultural habits they were forced to leave behind and experienced difficulties adjusting to their new environment. Most hoped to reach the United States. Some looked to continue to Central or South American countries to reunite with relatives, while others made inquiries to become settlers in the neighboring Dominican Republic colony of Sosúa.

Although displacement felt like a fracture for the refugees, those who were able to obtain Haitian nationality faced uprooting differently. The legislative amendment of 29 May 1939 brought about a modification to the previously established law of 29 November 1937, which allowed for the acquisition of Haitian nationality in absentia if refugees demonstrated their intention to invest capital towards the advancement of the country’s industrial and agricultural sectors or any other government initiative. The annual tax for the naturalization letter was 1,500 gourdes. 127 individuals residing outside of Haiti obtained Haitian nationality because of this provision, primarily through Haiti’s consulates in Brussels, Geneva, Hamburg, London, Paris, Le Havre, La Havana, Kingston, and Ciudad Trujillo.

After becoming naturalized, Jews who had settled in Haiti engaged in commercial and agricultural endeavors as stated in their naturalization agreements, even though some fictitious companies were established to protect their capital, thanks to their new citizenship. Among the businesses they started between 1939 and 1941 were The Haitian Company of Agriculture, The Haitian Company of Baths and Thermal Sources of Terre-Neuve, The Central American Development Corporation, The Haitian Company for Agriculture and Commercial Credits, and The Haitian Mexican Petroleum Refining Corporation.

Fig. 4: Exterior view of the Maison Pantal in Port-au-Prince, around 1940-44. The business was started by Walter Meinberg and his Haitian partner, Gilbert Dorismond. Later, the factory belonged to him and his brother Erich Meinberg; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eva Aviad.

The Meinberg family is a notable example of exiles who have been able to successfully adapt to life in Haiti and remain there for decades. Walter Meinberg was born in 1896 in the German city of Braunschweig to a Jewish family. His cousin Alfred Meinberg (?–?) had hired him to work at the Meinberg bank in Berlin, where he stayed until it was sold in 1933. Meinberg’s father, a cattle and horse dealer who lost most of his business, committed suicide that same year. After this tragic event, Meinberg returned to Braunschweig to run the family farm and married Herta Mayer (1909–1981) in 1937. They stayed in Braunschweig until his arrest in October 1938, when he was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp. Because of her connections, Meinberg’s sister was able to obtain a visa for him from the Haitian Consul General in Hamburg, Henri Fouchard (?–?), so that he could leave Germany. His early release was contingent on his ability to leave the country. He was eventually released from the concentration camp and decided to move to the Caribbean to join his brother Erich Meinberg, who had already established himself there.

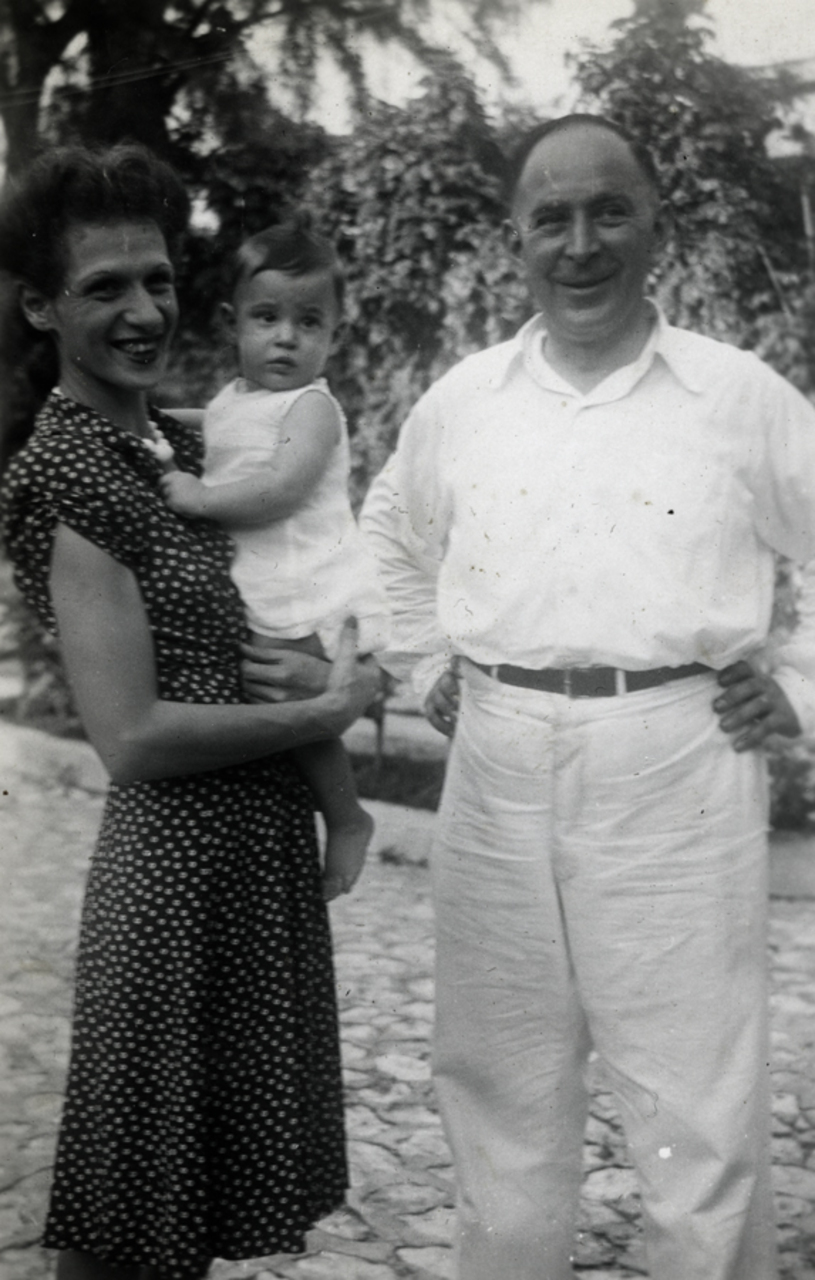

Meinberg’s older brother, Erich Meinberg (1899–1973), and his wife, Ruth Meinberg née Mielziner (1914–2022), had previously gone to Haiti on their honeymoon in 1937 and stayed, which simplified Walter Meinberg’s passage. Walter and Herta Meinberg were finally able to leave Europe in November of 1939. Herta Meinberg, who had studied fashion design in Germany, supported her family by making clothes for the upper classes in Haiti until her husband and brother-in-law began a business in Port-au-Prince, Maison Pantal, where they employed Haitian workers. They produced bowls, fans, and handbags from indigenous materials such as sisal, hemp, flax, reed, and wood. Both couples had children born in Haiti who later moved to the United States to pursue their education. Erich Meinberg returned to West Germany once in 1973 before passing away in Haiti at seventy-two. His funeral combined Jewish and Catholic services, and he was buried in Port-au-Prince.

Fig. 5: Close-up portrait of Herta and Walter Meinberg with their daughter Eva in Haiti, 1944; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eva Aviad.

His wife, Ruth Meinberg, struggled to adapt to life in Haiti. Following their divorce, she chose to return to West Germany with their son in 1960. Walter and Herta Meinberg stayed in Haiti until 1976, then joined their daughter Eva in Israel. Eva Aviad née Meinberg was born in Port-au-Prince in 1943 and remained in Haiti until 1958. She married Jacky Aviad, who worked at the Israeli Consulate in New York. After his service as Israel’s Consul General in Los Angeles, they lived abroad until his retirement in 1990, when they moved to Israel.

Fig. 6: Postwar photo of the cousins Anita and Eva Meinberg (on the right) dressed for Mardi Gras, sitting on an automobile, around 1949-51. Carnival in Haiti, celebrated with music, bands, and parades, is a cultural institution highly valued by the population. It ends on Mardi Gras, which is French for Fat Tuesday; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eva Aviad.

While some families, like the Meinbergs, the Salzmanns, or the Kalmars, managed to assimilate into their new surroundings, the presence of Jewish foreigners became a source of contention for a segment of Haiti’s elite society. The daily newspaper Le Nouvelliste and its conservative counterpart Le Matin largely relayed the points around which the dissensions caused by the arrival of these immigrants crystallized: first, the economic question: to what extent might these newcomers impose a burden on the state? Second, the issue of employment and wages: when allowed to work, thanks to a permit, it was believed that Jewish professionals would compete unfairly with local ones, particularly doctors. Finally, and perhaps the most sensitive issue, was the matter of cultural assimilation: Jews were depicted as a growing group forming within Haitian society that was voluntarily separate and unwilling to contribute to the national life.

Describing the presence of at most 300 immigrants within a population of over 3 million as a concern is disproportionate. These articles were more likely to represent the opinions and interests of a specific, economically and politically privileged Haitian minority. Antisemitism and anti-Judaism, as organized phenomena, never took root in Haiti. Today, the Jewish community numbers around twenty individuals on the island, but has a prominent presence in its business and economic life.

If some Haitians were skeptical of the validity and sincerity of the underlying reasons for the hospitality granted to the Jews, the prospect of migration to Haiti had not won over many Jewish advocates either. Reports from JDC employees described the country as primitive, severely impoverished, with an underdeveloped infrastructure and social standards. Those whose destination was Haiti were often designated as ‘unfortunate.’ An anonymous warning against such relocation sent to the President of the National Council of Jewish Women in Washington criticized the Haitian project as nothing more than a dishonorable and immoral scheme. It is alleged that its true purpose was to replenish the public treasury and circumvent American and international immigration laws.

Fig. 7: Group portrait of the Meinberg family in Haiti. Among them on the left: Erich Meinberg with his wife Ruth Meinberg (wearing a turban) and their daughter Anita. Eva Meinberg’s mother, Herta Meinberg, is in the middle. On the right: Ruth Meinberg’s sister, who married a local Haitian, Geo de Landes (next to her); United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eva Aviad.

It was Haiti’s elected president, Élie Lescot (1883–1974), who opposed naturalization in absentia and put any request on probation in October 1941, thereby ending Jewish immigration to Haiti during the Second World War. As late as 1948 and 1949, Jewish families were still indicating Haiti as their destination on the American Joint Distribution Committee Paris Emigration Cards after making the journey from their home countries or displaced persons camps to France to await final visas and travel arrangements. Haiti most likely served as a temporary stopover rather than a permanent destination, providing those families with an opportunity to await entry into another country within the northern or southern regions of the Americas.

A few years after the end of the war, in November 1947, as the preliminary vote at the United Nations session showed that three additional ballots were required to pass the resolution to establish the State of Israel, delegates of the Jewish Agency focused on persuading Haiti, Liberia, and the Philippines. Thanks to strong ties to the Black community of Pittsburgh, Mayor David L. Lawrence (1889–1966) was sent to New York to gain the support of Haiti. On the island, representatives of the Sephardic Jewish community intervened to convince President Dumarsais Estimé (1900–1953) to vote in favor of the creation of the Jewish nation. These missions were successful as, on 29 November 1947, Senator Emile Saint-Lôt (1904–1976), Haiti’s first United Nations Ambassador and a member of the Security Council, cast one of the deciding votes on behalf of President Estimé to pass Resolution 181.

Despite the founding of Israel, some Jewish families remained in Haiti until François Duvalier’s (1907–1971) autocratic regime came to power in 1957. Then, compelled by the prevailing poverty and violence, they left for the United States, Latin America, or Israel. The number of Jewish households in Haiti decreased to approximately twelve families during the 1970s. Today, Haiti’s Jewish community is very small, consisting mainly of descendants of Levantine immigrants, with no synagogue or distinct neighborhood in any major city. Religious observances are primarily conducted in private homes. In the absence of an Israeli embassy in Port-au-Prince, Reuven Shalom Bigio (*1973), a member of one of the oldest Sephardic Jewish families, serves as Israel’s honorary Consul and leader of the Jewish community.

Although most refugees left the island, the 1938 gesture of humanity on the part of the Haitian government toward the Jewish people was remembered. Jewish and Israeli organizations were among the first ones to assist Haiti following the devastating earthquake that struck on 12 January 2010. As rescue teams reached Port-au-Prince, children of refugees born on the island or who were very young when they arrived formed an online group to ‘reconnect with their past’ and draw attention to the unfolding disaster. Like the rest of the archipelago, Haiti bears the traces of the many communities that have shaped its social landscape over time. While mainstream historical narratives have often overlooked the Jewish community's contributions in the region, literary writers have filled this gap. Through their works, authors have brought to light the numerous ‘crossings’ between Jewish and Black communities, weaving a rich and intricate tapestry of the Caribbean’s cultural heritage. What other hidden stories might be revealed between Haitians and Jews as we continue to uncover new threads?

Haiti Refugee Legacy Project created by Harriet and Bill Mohr: https://haitiholocaustsurvivors.wordpress.com/documents/item-1-%E2%80%93-the-mohr-family-immigration-and-the-new-york-times/

Online Exhibition Closed Borders. The International Conference on Refugees in Évian 1938, Haiti: https://evian1938.de/en/haiti/

JDC Archives, Records of the New York Office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Haiti, Folders 691 and 692.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Nadège Veldwachter is an Associate Professor of Francophone Literatures and Cultures at Purdue University. Her research interests include literary sociology, globalization, translation, postcolonial historiography, and genocide studies. She is one of the founding members of the Genocide and Human Rights Research in Africa and the Diaspora (GHRAD) Center at Northeastern Illinois University. Dr. Veldwachter’s articles have been published in scientific journals such as Cahiers d’études africaines, Literary Studies, Research in African Literatures, Modern Language Notes, or Shofar. She is the author of Littérature francophone et mondialisation, published by Karthala editions, Paris, in 2012. Her current research examines the Second World War and the Shoah from a Caribbean perspective.

Nadège Veldwachter, Haiti’s Humanitarian Offer: Jewish Refugees in the Caribbean During the Second World War, in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, August 20, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-32> [February 26, 2026].