Born on March 11, 1889 in Ober-Heiduk, municipality of Königshütte (Chorzów), Germany (today Poland)

Died on June 24, 1966 in Leeds,

England

Occupation: Pacifist, teacher of German, art history, and theatre

Migration: Great

Britain, 1924

In August 1936, the German teacher and internationally renowned peace activist Martha Steinitz wrote an open letter to The Friend, the world’s most significant Quaker weekly, published in London. In her letter, she protested against the view that Jews had no right to the establishment of a national ‘homeland’ in the League of Nations’ Mandate for Palestine. By introducing herself to readers right at the beginning as “a pacifist and socialist, and as a Jew” Martha Steinitz, “Jews in Palestine”, in: The Friend, 14 August 1936, 768., she increased the moral pressure to take her position seriously. Steinitz not only called on the Christian-influenced Quaker community to raise its voice against antisemitism, but also to condemn the acts of terror committed against Jews in the British Mandate during the ongoing so-called Arab revolt since April 1936. This letter is remarkable in part because it was written from the perspective of a Jewish German woman who had emigrated to Britain eight years before power was transferred to the National Socialists in 1933 and had since become a British citizen. Addressing the British Quakers—a community committed to peace, nonviolence, and social justice—she highlighted the foreign and domestic political consequences of hatred toward Jews. Steinitz did this not least with full awareness of the increasingly aggressive persecution policies of the National Socialists, which also threatened her family members in Germany. From her longtime place of residence in the northern English city of Leeds, she helped many people with their escape and during their arrival in the United Kingdom. Steinitz’s humanitarian work for refugees amounts to a snapshot of her decades-long activity as a cultural mediator between Germany and the United Kingdom.

Fig. 1: Martha Steinitz at the Honorary Degree Ceremony on 18 May 1961 at Leeds University. Reproduced with the permission of Cultural Collections and Galleries, University of Leeds Libraries, Leeds University Archive, [LUA/PHC/005/36].

Martha Steinitz was born as the tenth and youngest child of Ida Steinitz (1848–1889) and Hermann Steinitz (1838–1892), a trained locksmith, in Ober-Heiduk, a district of the city of Königshütte (Chorzów), which at the time belonged to Prussia. Her father took a position as procurement manager and authorized signatory (Prokurist) at the nearby Bismarckhütte ironworks (Chorzów Batory). A year before Steinitz’s birth, he had signed an employment contract there that guaranteed the family an apartment and a pension. Both would prove crucial to securing the family’s modest middle-class existence, because two weeks after Steinitz’s birth, her mother died unexpectedly, and her father only three years later. From then on, her aunt Selma Steinitz (1852–1938) took over the upbringing of the children. She did her best to cultivate their intellectual and musical talents. In this way, Steinitz learned to play the piano.

Little is known about her youth in the historical region of Upper Silesia. Judaism apparently played a minor role in the family’s everyday life. As a young woman, Steinitz first learned the touch typing system for typewriters, which enabled her to take a job at the Berlin branch of the Upper Silesian Ironworks (Oberschlesische Hüttenwerke). Later, she completed teacher training, passed the state examination, and worked as an educator in Paris. Her command of the French language is likely due to this period of employment.

Fig. 2: Martha Steinitz on the lap of her aunt Selma Steinitz, her sisters, and her brother Georg (Jorg) can be seen in the background, around 1900; Private collection Yuval L. Steinitz, Jerusalem, Israel.

After the First World War, Steinitz became politically active in Berlin. She was involved in several pacifist organizations, including the German Peace Society (Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft) and the New Fatherland League (Bund Neues Vaterland). From 1922 to 1924, she headed the Berlin office of the League of War Resisters (Bund der Kriegsdienstgegner), the German section of the London-based War Resisters’ International (WRI). Founded in 1921, this network developed into an advocacy group for antimilitarist and pacifist organizations and individuals. Following the First World War, the most costly war to date in Europe, with millions of deaths, its founding declaration advocated a comprehensive understanding of conscientious objection. For its authors, war constituted “a crime against humanity,” which is why they were determined “to strive for the removal of all causes of war.” War Resisters’ International (ed.), War Resisters of the World. An Account of the Movement in twenty countries and a Report of the International Conference held at Hoddesdon, Herts., England, July 1925, Enfield, Middlesex: War Resisters’ International, 1925, 9.

Fig. 3: Portrait of Martha Steinitz captioned “Fraulein Steinitz”, in: No More War [London], vol. 1, no. 1, 10 February 1922, 4.

Steinitz collaborated in the German League of War Resisters with notable figures such as Armin T. Wegner (1886–1978), Arnold Kalisch (1882–1956), and Erna Kalisch (1889–1961), as well as Kurt Hiller (1885–1972) and Helene Stöcker (1869–1943). She also represented the organization outside Germany, thereby contributing early on to the development of a transnational network of the peace movement. At an event jointly organized by British, German, and French anti-war activists in London in February 1922, Steinitz impressed the audience with her account of the annual “No More War” rallies, which attracted up to 200,000 people in Berlin’s Lustgarten alone. Among them were celebrities such as the physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and his wife Elsa Einstein (1876–1936).

Fig. 4: Elsa Einstein (center) at the “No More War” rally in Berlin’s Lustgarten, 31 July 1921. Standing behind her, wearing a light-colored hat, is the women’s rights activist Maud von Ossietzky (1884–1974); Archive of the Peace Pledge Union and War Resisters’ International, London.

In the spirit of the peace movement, Steinitz wrote articles, reports, and reviews for progressive journals such as Die Friedens-Warte, Die Neue Generation, Die Frau im Staat, and Die Neue Erziehung. She also published pamphlets and books, and took part in events such as a lecture series organized by the Berlin branch of the German Peace Society, where the organization’s then–executive secretary, the writer and future Nobel Peace Prize laureate Carl von Ossietzky (1889–1938), also spoke. On 21 June 1920, Steinitz delivered a lecture against racism, denouncing it as one of the causes of war. The critique of racism remained a recurring theme in her essays throughout the following decade. She emphasized the shared origins of modern movements for emancipation, such as the abolition of slavery and the struggle for women’s rights. Her sensitivity to antisemitism led her, certainly by the spring of 1938, to admonish her friends in the WRI for underestimating the significance of hatred toward all things Jewish as a core element of the Nazi regime’s racist ideology.

Between 1923 and 1934, Steinitz’s pacifist commitment focused primarily on the WRI. Together with its chairman, Fenner Brockway (1888–1988), she managed the affairs of the executive committee alongside the Honorary Secretary, Herbert Runham Brown (1879–1949), initially as Associate Secretary, and later also as Literature Executive. Within this body, which at times comprised up to 14 people from ten different countries – including five women – Steinitz was highly valued for her organizational skills, programmatic proposals, journalistic activities, and connections to the German peace movement. Her Jewish background played no significant role until the transfer of power to the National Socialists; during the 1920s, she was regarded primarily as a representative of the German peace movement. What is remarkable, however, is a letter she wrote to Albert Einstein in Berlin in which she, on WRI letterhead, declared herself both a Zionist and a pacifist.

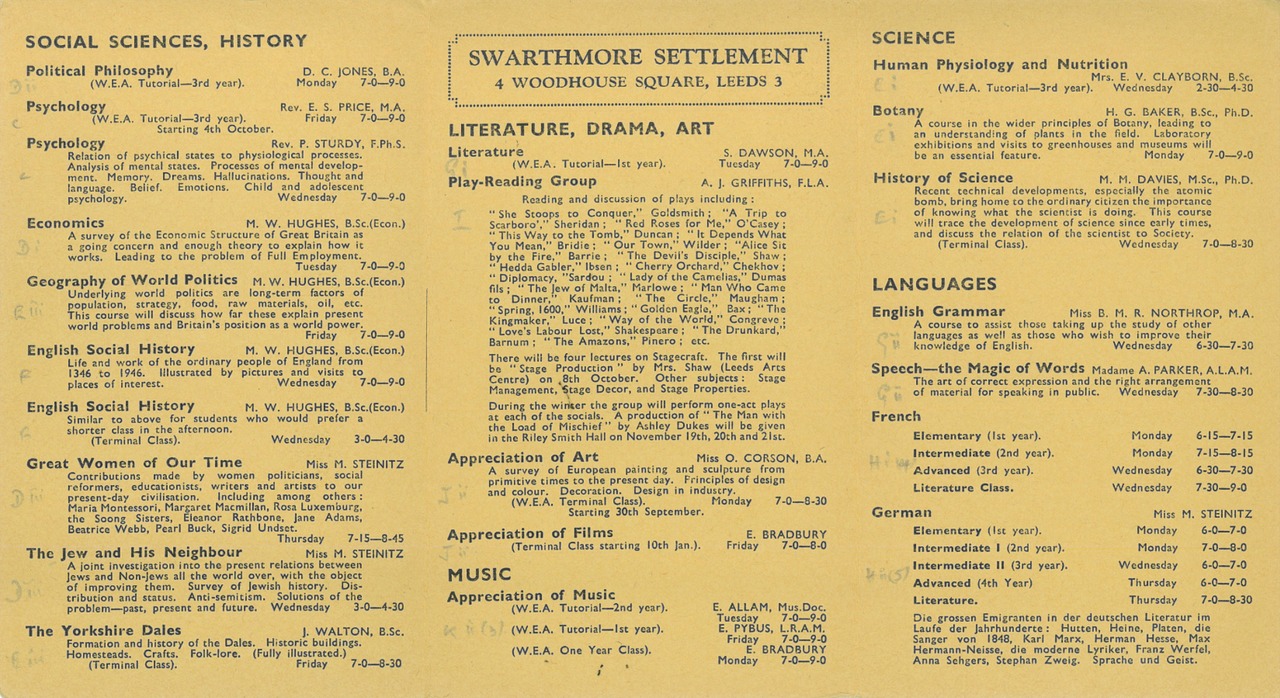

In order to devote herself entirely to the WRI, Steinitz moved permanently to England during the second half of 1924. The exact circumstances and precise chronology of her emigration are not completely clear. She may have already made this decision after spending Christmas of 1921 there with the Quaker family of Lucy Whiting (1858–1951) and William Whiting (1856–1934). This contact arose through her connections to the British peace movement, in which many members of this religious community were deeply engaged. Family memories also indicate that upon her emigration, Steinitz initially stayed in a London home for young women, run by Lily Montague (1873–1963), a social worker and important representative of Liberal Reform Judaism in the United Kingdom. From 1925 until the early 1930s, Steinitz lived in the Whitings’ home in Headingley, a northern district of Leeds. From 1929 until her death, she earned her living as a teacher at Swarthmore Settlement, a Quaker educational institution for adults. In September 1933, eight months after Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) was appointed Chancellor, Steinitz became a British citizen.

Steinitz’s intensive work for the WRI greatly expanded the organization’s reach. Her annual trips to Germany also contributed to this, serving both for family visits and for peace movement campaigns. On 30 August 1930, for example, during a visit to Einstein’s summer house in Caputh near Potsdam, Steinitz, together with pacifist Harold Frederick Bing (1898–1975), convinced the famous physicist of the legitimacy of the stance taken by some conscientious objectors in rejecting even civilian alternative service.

Thanks to her native German and her excellent command of English and French, Steinitz handled translation work and correspondence for the WRI. In addition, she helped to organize the major triennial conferences, which her nephew, Esra Erich Steinitz (1902–2001), also attended. Because his own life was in danger due to the transfer of power in 1933, he fled Germany, eventually reaching England via several stops to join his aunt. Through her friend Selig Brodetsky (1888–1954), a mathematics professor and later president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, she helped him obtain entry papers for the British Mandate of Palestine. As a result of his life-saving Aliyah in the winter of 1935, he adopted the second name Esra and initially worked in the moshav of Nahalal on the farm of Natan Hofshi (1889–1980) and Tovah Hofshi (1888–1968), west of the city of Nazareth. The peace movement’s network had helped him make the connection. Natan Hofshi was one of the WRI’s representatives in Palestine, since the better-known Hans Kohn (1891–1971), historian and former member of the pacifist Brit Shalom, had emigrated to the United States of America in 1934. During a five-week trip to Israel in the late summer of 1950, Martha Steinitz also visited Hofshi, with whom she had already been in correspondence for over two decades.

Through the courses in German language and literature that she offered regularly from September 1929, Steinitz shaped the adult education center in Leeds – today known as the Swarthmore Education Centre – for nearly four decades. Her favorite author, Goethe (1749–1832), whose Faust (1808) she translated into English for teaching purposes, was frequently part of the curriculum. On the occasion of Swarthmore’s fiftieth anniversary in 1959, she even composed a short ode to Goethe, linking one line to her warning against the escalation of the so-called Cold War: “All knowledge liberating our intellect without increasing our self-control is dangerous. (Vide: the atom bomb!)” Martha Steinitz, “Goethe (1749–1832). Prophetically on and to Swarthmore”, in: Swarthmore Jubilee Magazine 1909–1959, Leeds 1959, 39.

Early on, Steinitz began writing her own plays and staging them with the participants of her German courses. Her greatest success came in 1951 with the production of Buddenbrooks (1901) by Thomas Mann (1875–1955). She had written a letter to the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, asking for his approval for her dramatization of his novel, for which Mann subsequently congratulated her. She also corresponded with the philosopher of religion Martin Buber (1878–1965), who had been living in Jerusalem since 1938, regarding her English-language adaptation of his Die Legende des Baal-schem (1908).

Beyond her teaching in art and music history, (exile) literature, theatre, and German language, Steinitz developed courses between 1943 and 1947 on the history and religion of Judaism, Zionism, and on combating antisemitism.

Fig. 5: Swarthmore Settlement, Programme Winter 1946-47. Steinitz introduced her students, among other topics, to the works of the “great emigrants in German literature over the centuries”; Archive: Swarthmore Education Centre, Leeds.

After Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938, the British government issued new entry regulations in April. Anyone wishing to enter the country now had to apply for a visa in a time-consuming process. Approval also depended on whether the applicant could provide a financial guarantee or a concrete job offer to cover living expenses in the country. Despite these obstacles, more than 60,000 refugees reached Britain by the beginning of the war in September 1939. Jewish relief organizations played an important role in this effort, such as the Jewish Refugees Committee, founded in the spring of 1933 by the Frankfurt-born banker Otto Schiff (1875–1952), and the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR), which began its work in July 1941. Steinitz used her contacts with both organizations, her friends at the WRI, and the Quakers to assist Jewish and non-Jewish refugees in coming to the United Kingdom. Furthermore, she raised public awareness of the problems and hardships faced by this group.

Later in 1939, Steinitz gradually brought four of her sisters from Breslau (Wrocław) to England, thus saving them from murder by the National Socialists. In early summer 1940, when the four were interned on the Isle of Man as ‘enemy aliens’ due to their German citizenship, Steinitz, by writing dozens of letters, secured their release: Hedwig Steinitz (1882–1975) and Klara Steinitz (1885–1964) were the last to return, on 1 March 1941, to their sister’s home. Since the summer of 1937, one of her nephews had already been living there. Thanks to her employment at Swarthmore – and the fact that Klara Steinitz also sporadically offered German courses there from 1943 onwards – Steinitz was able to provide several relatives seeking protection with a place to live under her roof.

Fig. 6: Else Opel née Lichtenstein (1881–1963) with her cousins Martha, Klara, Margarete (1873–1949) and Gertrud Steinitz (1876–1950) – from left to right –, after the Second World War, photographed in front of Steinitz’s house in Leeds; Private collection Yoram Steinitz, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Her small terraced house became a well-known place of contact for other refugees, such as Margot Hodge née Pogorzelski (1920–2014), a trainee nurse also from Silesia. After Steinitz paid a £50 guarantee, the nineteen-year-old stayed with the Steinitz sisters for several weeks from July 1939 and was able to continue in Leeds her nursing training, which she had begun at the Jewish Hospital in Berlin.

Not least through long-standing friendships – for example, with Esther Simpson (1903–1996), the secretary of the Academic Assistance Council in London – Steinitz maintained contacts with nationwide relief organizations. In cooperation with the local section of the Leeds Jewish Refugees Committee, the counterpart to the Quakers’ Leeds Committee for Non-Jewish Refugees, she herself began in June 1940 to offer evening classes for new arrivals who wished to learn English. Where and how Steinitz had acquired such excellent language skills before her own emigration remains unknown. Unlike the vast majority of refugees, she was thereby at an advantage and sought to put her wide network of contacts and her teaching experience to use accordingly. Not least through these courses, Steinitz assumed an important role as an intermediary. She deliberately sought to promote the social integration of the newly arrived. In 1946, for example, she wrote to the editors of AJR Information, the newsletter of the AJR: “From the time of their arrival it has been my object to get them into personal touch with my numerous English friends, with the result that all those Jewish refugees who wished to move out of their somewhat confined circle were able to form valuable friendships, widening their horizon and, incidentally, that of their Gentile neighbours and friends.” Martha Steinitz, “Letters to the Editor”, in: AJR Information, no. 5, May 1946, 38.

After the end of the war, Steinitz explicitly acknowledged the activities of the AJR and remained connected with them, as later recalled by historian Caesar Caspar Aronsfeld (1910–2002), who had also fled to Leeds and played a key role in establishing what is today the Wiener Holocaust Library in London.

In 1961, the University of Leeds awarded Steinitz an honorary Master of Arts in recognition of her life’s work. She died unexpectedly on 24 June 1966, at the age of 77, in Leeds General Hospital from cancer, a diagnosis that came too late. Steinitz was buried in the historic Lawnswood Cemetery. In her memory, Swarthmore established the Martha Steinitz Fund, which enabled talented students to travel to Europe to take courses in art history, music, or German language and literature. The fund, commemorating Steinitz’s reputation as a mediator for peace and understanding, eventually dried up in the spring of 1980, when Swarthmore awarded the last two scholarships for a summer course in German at the University of Vienna.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Dominique Miething is a lecturer at the Freie Universität Berlin’s Otto Suhr Institute of Political Science. His research and teaching focus on the history of political ideas and on teacher training in civic education, specializing in peace education and peace history, and in combating antisemitism, authoritarianism, as well as right-wing extremism. He is particularly interested in studying engagements with historical and political issues at museums and memorial sites and their didactical settings. Among his publications are Anarchistische Deutungen der Philosophie Friedrich Nietzsches. Deutschland, Großbritannien, USA [Anarchist Readings of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Philosophy. Germany, Great Britain, USA]. 1890–1947, Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2016; Erasmus von Rotterdam: “War is sweet to those who have no experience of it …” - Protest against Violence and War [= Publication series: Exhibitions on the History of Nonviolent Resistance, no. 1, Christian Bartolf/Dominique Miething (ed.)], Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 2022; “Emma Goldman (1869–1940)”, in: Thomas Friedrich (ed.), Handbuch Anarchismus, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2022, n.p.; “Antisemitism in the anarchist tradition”, in: Anarchist Studies, vol. 26, no. 1 (2018), 105–108.

Dominique Miething, Martha Steinitz (1889–1966), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, August 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-33> [February 21, 2026].