Born on October 2, 1894 in Schweizer-Reneke, South Africa

Died on August 23, 1966 in Cape

Town, South Africa

Occupation: Artist, painter, sculptor

Migration: Germany,

1901/1914 | South

Africa, 1920 (Between 1901 and 1920, Stern commuted between Germany and South Africa)

“Today I accepted an invitation to Swaziland. The car drove through remote areas to a remote village – consisting of just a few huts. And here, in front of a hut, I found three girls of enchanting beauty, whom I immediately tried to capture.” Irma Stern, “Drei Swasimädchen“, in: Frau und Gegenwart. Zeitschrift für die gesamten Fraueninteressen. Offizielle Ankündigung des Stadtbundes Hamburgischer Frauenvereine und des Verbandes Norddeutscher Frauenvereine, no. 16, 1927, 3. „Heute folgte ich einer Einladung nach Swasiland. Das Auto fuhr durch einsame Gegenden in ein abgelegenes Dorf – bestehend aus nur wenigen Hütten. Und hier vor einer Hütte fand ich drei Mädchen von zauberhafter Schönheit, die ich sofort festzuhalten versuchte.“ (translation by the author) This scene, described in a travelogue to Swaziland by the South African-German Jewish artist Irma Stern, is also visually depicted in a painting entitled “Three Swazi Girls”, which was created around 1925, presumably in the context of this journey. In the visual language and aesthetics of Expressionism, the painting shows three women standing side by side, closely embraced in front of the hilly green landscape of Swaziland. They are wearing traditional clothing and jewelry, and their heads are adorned with the gray clay headdress of Swazi women.

In 1927, the painting was reproduced under the title “Three Swazi Girls with Clay Headdresses” in the German magazine Frau und Gegenwart, together with the quoted text. This circulation of Stern’s life and works between Germany and South Africa in the first half of the twentieth century is exemplary and particular for the artist. It is also evident in her artistic expressions, which illustrate the encounter and cross-cultural contact zones of German Expressionism with themes and motifs of South Africa.

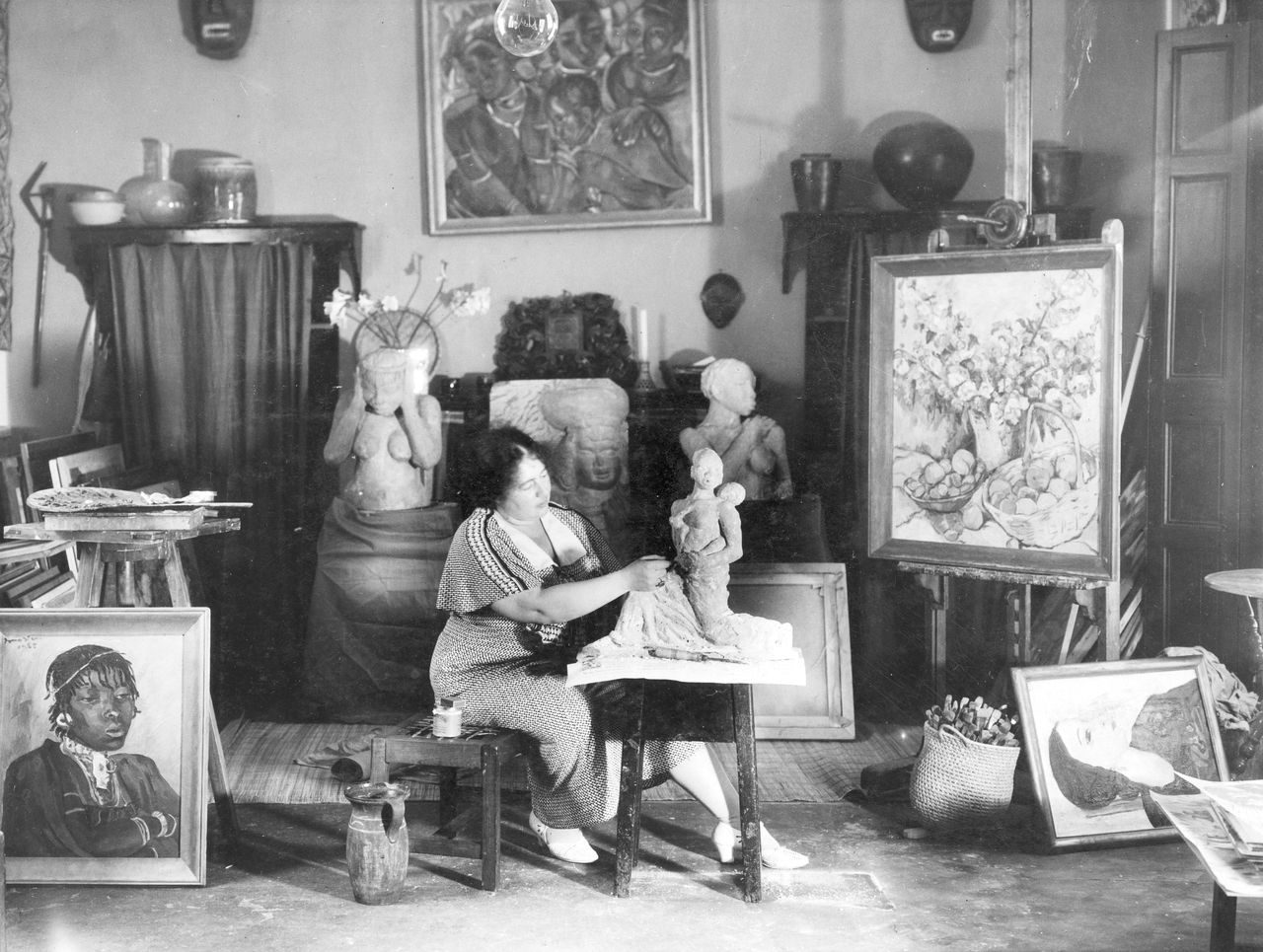

Fig. 1: Irma Stern in her studio in Cape Town, 1936; National Library of South Africa, Cape Town. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Irma Stern Collection, Cape Town.

Fig. 2: Irma Stern, “Three Swazi Girls”, around 1925; Collection UCT Irma Stern Museum, Cape Town. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Irma Stern Collection, Cape Town.

Irma Stern was born and spent her early childhood years in Schweizer-Reneke, a village in the southwest of the Transvaal Republic of South Africa. Her parents, Samuel (1863–1935) and Henny Stern née Fels (1875–1944), were German-Jewish immigrants who owned a farm and a small trading business. Samuel Stern was born in 1863 in Reichensachsen, in the Electorate of Hesse, Germany, where a small Jewish community had established itself. As a young man, he tried his luck as a businessman in the USA. When Samuel Stern failed there, he moved to South Africa, where he quickly became successful with his trading activities. During the nineteenth century, several Jewish migrants from the German lands helped create an efficient trading network connecting South Africa with Europe. Their activities attracted scores of more German-Jewish families to trickle in. In 1893, during a short stay in his old home country of Germany, Stern married Henny Fels, who lived in Hanover, and moved to South Africa with him out of a thirst for adventure. In the course of the South African War (1899–1902), the family had to flee and moved to Cape Town. In 1901, when the bubonic plague broke out in the city, the Jewish population was increasingly exposed to antisemitic resentment. Against this background, the Sterns decided to return to Germany.

Between 1901 and 1920, the family commuted between Germany and South Africa. Thus, Irma Stern grew up in and between both worlds. After the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the family had to stay in Germany until 1920. Thus, it was not until then that Stern returned to South Africa with her family. She settled in Cape Town – usually the port of arrival for German-Jewish immigrants – and lived and worked as an artist until her death in 1966.

Irma Stern decided to become an artist at an early age. From 1912, she attended the private Reimann Art School in Berlin. But she did not feel she was making any progress in her artistic work there. Instead, she wanted to go to a state art academy: a difficult undertaking, as women were not allowed to study at art academies at that time. Stern was finally accepted into the women’s class at the Grand Ducal Academy for Fine Arts in Weimar (Großherzoglich-Sächsische Hochschule für Bildende Kunst in Weimar) in 1913. However, she moved back to Berlin in 1914. It was, in particular, Stern’s encounter and friendship with the successful expressionist artist Max Pechstein (1881–1955) in 1917 that paved her way into the Berlin art scene. Their common interest and enthusiasm in primitivism – an artistic movement and style of modernism in search of the origins of art and life, which it found in the art and culture of indigenous peoples – connected them in a lifelong friendship between Cape Town and Berlin. It found expression in numerous letters and works of art.

In 1918, Stern was a founding member of the artistically revolutionary Novembergruppe (November Group) in Berlin and took part in its exhibitions in 1919, 1920, and 1927. In 1919, the renowned Galerie Fritz Gurlitt in Berlin dedicated a solo exhibition to her work, which was very well received by the art world and the press. The exhibition included paintings with themes and motifs from Stern’s South African homeland, executed in the artistic style and avant-garde aesthetics of German Expressionism. In the context of her meteoric rise in the Berlin art world and in Europe, the German-Jewish art critic and journalist Max Osborn (1870–1946) dedicated the first monograph to Stern’s work in 1927, entitled Irma Stern. Mit einem Auszug aus dem „Tagebuch einer Malerin“ und 32 Bildern (Irma Stern. With an Excerpt from the “Diary of a Painter” and 32 Images). The monograph appeared in the series Junge Kunst, in which Osborn had already written a volume on Max Pechstein. Other artist monographs that were published in this renowned series included Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907). In comparing Irma Stern with the French painter and sculptor Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), however, Osborn emphasized her peculiarity, namely the fact that her gaze on Africa was not that of a traveler discovering the Other, but a familiar one, on her own homeland.

In 1920, Irma Stern returned with her family to South Africa, where she settled in Cape Town and continued her work as an artist. Two years later, she had her first major exhibition in the city. However, her way of living and working as a woman in a male-dominated art world, her choice of themes and motifs as well as the use of avant-garde expressionist aesthetics and visual language, caused controversy and was met with great criticism, especially in conservative circles of the White colonial society. As a woman, Stern moved in avant-garde circles in European metropolises while simultaneously in areas of South Africa and the African continent seemingly untouched by ‘civilization’.

The negative reception and rejection of Stern’s artistic work in South Africa continued even after her death. They were sometimes pejoratively described and interpreted as the result and a counter-image of her supposedly opulent appearance and frustration. Against the backdrop of this hostility, Stern turned to like-minded people, to friends and colleagues in the cultural circles of Jewish intellectuals in Cape Town and Johannesburg, most of whom had immigrated from Lithuania or Germany. At the turn of the twentieth century, around 40,000 Lithuanian Jews came to dominate South Africa’s Jewish community in search of economic opportunity. Their arrival coincided with a period of growing local antisemitism. The idea that Jews were ‘unassimilable’ had found increasing support during the 1920s in South Africa, especially in Afrikaner nationalist circles.

Among those immigrants from Europe were the teacher and journalist Roza van Gelderen (1890–1976) and her life partner, the writer and teacher Hilda Purwitsky (1901–1998), as well as the cultural professional Richard Feldman (1897–1968). Van Gelderen was born into a prestigious Dutch family in Amsterdam, who settled in Cape Town in 1903. Hilda Purwitsky arrived in Cape Town in 1901 as a baby, immigrating with her parents from Lithuania. Stern and her Jewish friends were close to the Jewish community in Cape Town and always active in their circle. Numerous portraits by the artist bear witness to these artistic friendships, as well as appreciative reviews and critiques of her work in the press and publications by them. The diverse countries of origin of the Jewish circle of Stern’s friends are also reflected in the languages they used to communicate with each other and discuss their artistic work, such as English, Dutch, German, and Yiddish.

Fig. 3: Irma Stern, „Roza van Gelderen“, 193(?); Collection UCT Irma Stern Museum, Cape Town. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Irma Stern Collection, Cape Town.

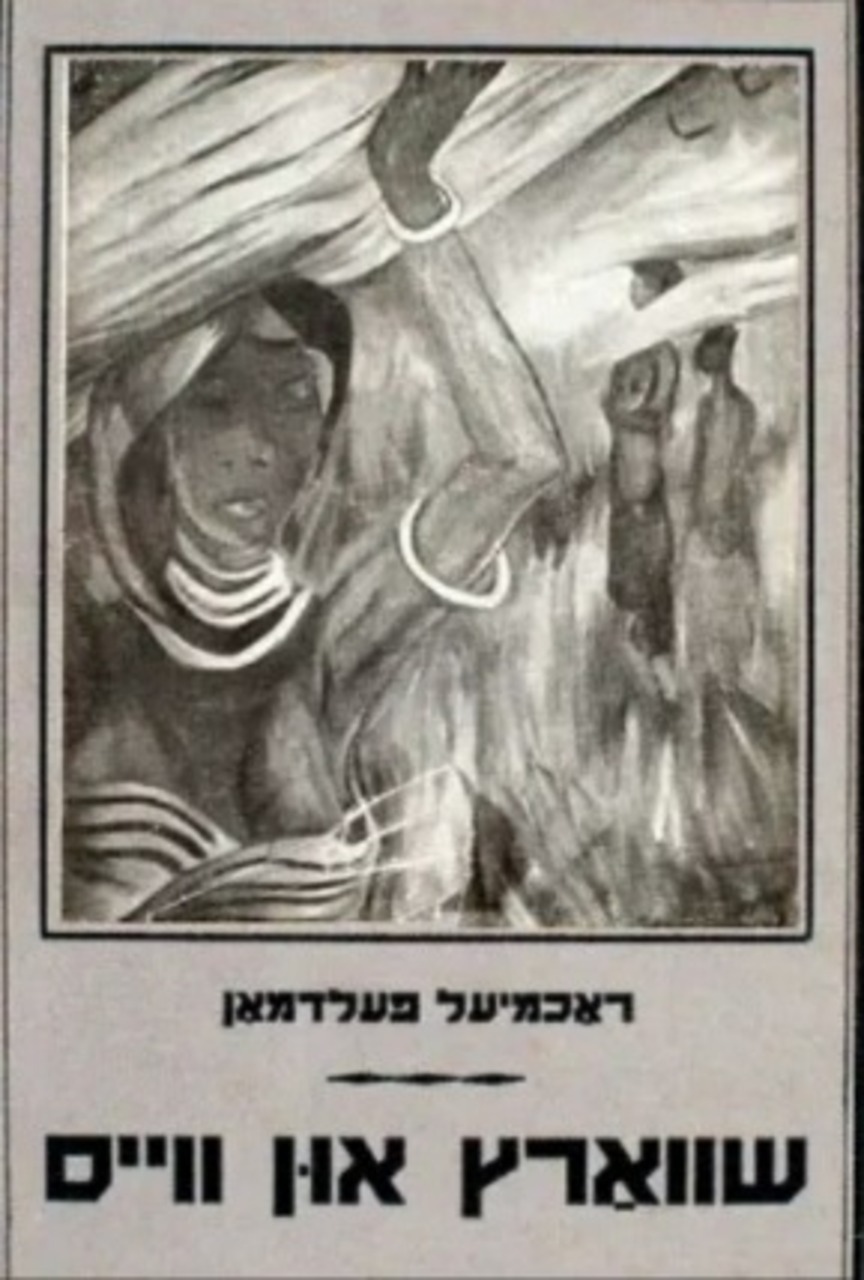

In this context, it was particularly Feldman’s home in Johannesburg, which served as a place for artists, writers, musicians, and actors, especially from the Yiddish communities. Richard Feldman was born in Lithuania in 1897 and worked in a Kibbutz in Mandatory Palestine as a convinced Zionist and socialist in the 1920s, before settling in Johannesburg. Most European Jews made their way to South Africa’s commercial center, where Feldman established a business in tobacco and published regularly on politics and culture. Stern and Feldman became close friends and admirers of each other’s work. Thus, when Feldman published a book of Yiddish short stories entitled Schvarts un Veys (Black and White) in 1935, a socially critical portrayal of the working class, which addressed and criticized the problems of racism in South Africa, Stern gave him four of her paintings to illustrate his work and to support his political and socially critical commitment.

Fig. 4: Richard Feldman, Schvarts un Veys (Black and White), 1935, with illustrations by Irma Stern. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Irma Stern Collection, Cape Town.

When the Nazis seized power in 1933, Stern broke off her contacts in Germany and no longer exhibited there. With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 and the fact that, as a Jew, she could no longer travel to Germany and Europe, Stern concentrated her artistic work and travel activities on the African continent. From 1939 to 1945, she spent long periods in Zanzibar and the Congo. The South African writer and scholar Claudia Braude (*1967) suggests reading these journeys as directly related to Stern’s German-Jewish identity and the developments in Germany after 1933. According to Braude, Stern set out in search of alternatives to the supposed ‘European civilization’, which was now developing into barbarism. She hoped to find culture and civilization among the indigenous population of sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, Stern’s travels and associated artistic works can be understood as a continuation of Expressionism, even as a political act of resistance. At the beginning of the twentieth century, primitivism was seen as a counter-image to European industrialization.

Stern shared and exchanged these views with the ethnologist Leo Frobenius (1873–1938) from Frankfurt, whose scientific work involved exploring African cultures and warned against their destruction through the colonization of the continent by the Europeans. Stern and Frobenius were united by the desire to use their work to revise the racist image of the indigenous peoples and cultures of Africa circulating in Europe.

Stern took a critical position on the so-called ‘civilization’ and spoke out against the colonialist ‘modernization’ of South Africa and its threat to the living conditions, traditions, and cultures of the various ethnic groups. It can be seen as Stern’s main concern for travelling the African continent, especially to areas seemingly untouched by ‘civilization’. There, Stern captured nature, people, and cultures in her artistic works. However, her paintings and written testimonies are not free of exoticizing, romanticizing, and civilizational gazes on the African continent. While Stern challenged colonial perceptions of indigenous peoples, her own European perspective eventually shaped that approach and reveals colonial power dispositions of the time.

Stern’s life and work raise manifold questions of belonging and recognition. As a German-Jewish South African artist, she succeeded in rising in the artistic avant-garde circles in Berlin in the 1920s. While her artistic work was positively received in Germany, it was received in the opposite way in South Africa, where she found encouragement and support for her work in Jewish intellectual circles.

Due to the systematic exclusion and persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany and the lack of recognition in her home country of South Africa, where, as a Jew, she also did not belong as part of the White colonial society, Stern lived and worked in an in-between space throughout her life. Against this background, she embarked on a search for herself, for her sense of belonging, which she hoped to find in the cultures and peoples who lived seemingly untouched by the barbarism of European civilization. Thereby, Stern related to her surroundings through her artistic work. In particular, the portraits of women and the female body of indigenous women, which are central to her work, can be regarded as a means of identification in the context of Stern’s personal and artistic search for herself and her sense of belonging.

Fig. 5: Irma Stern in her studio in Cape Town, around 1945; Collection UCT Irma Stern Museum, Cape Town. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Irma Stern Collection, Cape Town.

Today, Stern is recognized as a pioneer of modern art in South Africa. Her oeuvre comprises around 800 paintings as well as numerous drawings, watercolors, prints, sculptures, and ceramics. The themes and motifs of her artworks, executed in the visual language and aesthetics of Expressionism, which she brought in the sense of a cultural transfer from Germany to South Africa, include particularly still lifes and portraits of the indigenous population of the African continent. A large part of Stern’s work is kept in her house and studio in Cape Town, which is now home to the Irma Stern Museum.

In Germany, her life and work fell into oblivion. In recent years, the first scholarly attempts have been made to bring Stern back into the spotlight. In 1996/1997, she was rediscovered in Germany by the art historian Irene Below (*1942), who dedicated an exhibition to her at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld and analyzed the artist’s life and work for the first time from a feminist and postcolonial perspective. In 2025, the Brücke-Museum holds the first solo museum exhibition in Stern’s former home city of Berlin to present her art of global modernism and reflect on it from a queer Black perspective.

Irma Stern Museum, Cape Town: https://irmasternmuseum.co.za/

Special Exhibition „Irma Stern. A Modern Artist between Berlin and Cape Town” (July 13 – November 2, 2025), Brücke-Museum: https://www.bruecke-museum.de/en/programm/ausstellungen/3817/irma-stern-a-modern-artist-between-berlin-and-cape-town

Documentary „Das Regenbogenkap der Malerin Irma Stern“, in: Stadt, Land, Kunst – ARTE, February 20, 2024: https://www.arte.tv/de/videos/118907-001-A/das-regenbogenkap-der-malerin-irma-stern/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Anna Sophia Messner is an art historian and scientific staff member in the European Research Council project MEDMACH (https://medmach.hypotheses.org/team-members/anna-sophia-messner) at the Institute for Cultural Studies, Department of Transcultural Studies at the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (https://www.kunstgeschichte.hhu.de/teams/anna-sophia-messner). Her research interests include Jewish art, culture, and historiography with a special focus on migration, exile, and transcultural exchange processes, as well as Jewish visual and material culture in the Mediterranean region. Her recent publications include: Photography and Migration, Special Issue of the International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020 (edited with Eva-Maria Troelenberg and Costanza Caraffa); Palästina/Israel im Blick. Bildgeographien deutsch-jüdischer Fotografinnen nach 1933 (Gazing at Palestine/Israel. Visual Geographies of German-Jewish Women Photographers after 1933), Göttingen: Wallstein, 2023; “Visualizing Marseille as a City of Transit”, in: Kristina Schulz/Doerte Bischoff/Moritz Wagner (ed.): Exilforschung. Ein internationales Jahrbuch, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2025, 221–237.

Anna Sophia Messner, Irma Stern (1894–1966), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, October 13, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-41> [February 28, 2026].