Dr. Arthur Ruppin (1876–1943), head of the Jewish Agency in Mandatory Palestine, visited the neighboring island of Cyprus in late May 1935. He traveled there to meet with Jews and report on the situation of the Jewish presence in the British colony. The trip was arranged in collaboration with a German-Jewish associate who had already settled on the island.

Upon his return to Jerusalem on June 5, Ruppin drafted a report on his trip. In this report, he detailed the places he visited in Cyprus, the people he met, and the cost of immigration and settlement on the island. His report also records the various business ventures undertaken by Jewish immigrants, including several German Jews. The source provides a comprehensive overview of the island’s German-Jewish presence in 1935 and discusses the prospects for future settlement in the British colony. The report is archived at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem.

Arthur Ruppin, originally from the Province of Posen (today Poland), served as the head of the Jewish Agency between 1933 and 1935. For many years, he was the Director of the Palestine Office of the Zionist Organization (ZO) in Mandatory Palestine, where he had moved in 1908, and was in charge of the organization’s land purchases. Ruppin played a pivotal role in organising Jewish settlements, as well as promoting Jewish migration from German-speaking areas to Palestine in the 1930s.

His visit to Cyprus occurred before the German-Jewish movement grew significantly on the island. By that time, Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) had already been in power for two years, and antisemitic policy had triggered a growing wave of Jewish migration out of Nazi Germany. As reflected in Ruppin’s report, Zionist circles from Germany and Mandatory Palestine were at that point looking for territories in the Eastern Mediterranean region to accommodate the settlement of German Jews. In the case of Cyprus, this effort was underway as early as 1933, with these circles attempting to lay the groundwork for the influx of Jewish immigrants from Germany to the island. They sought to take advantage of Cyprus’s geographical proximity to Palestine and explored the possibility of organising temporary Jewish settlements through investments in land purchases and private enterprises.

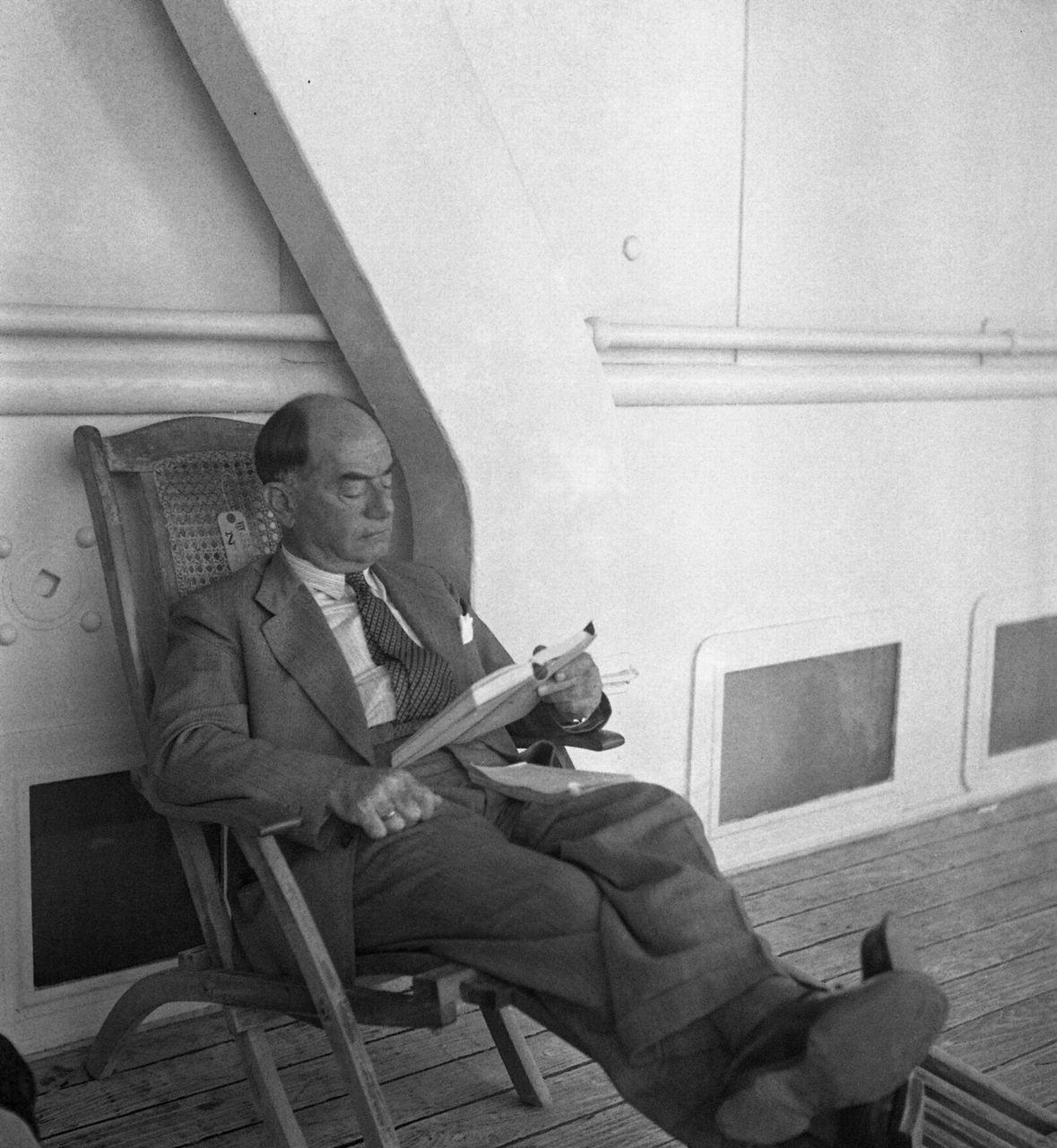

Fig. 1: Arthur Ruppin, who became widely recognized as the ‘father of Zionist settlement’, reading a book on a ship, 1935; Central Zionist Archives, AY327821.

Ruppin visited the island to have a first-hand understanding of the Jewish presence and assess the role Cyprus could play in providing shelter for Jewish immigrants. His report was primarily addressed to the Zionists in Mandatory Palestine, who were particularly interested in Cyprus’s prospects and were exploring alternative locations in the region as a solution to the growing issue of Jewish immigration. Ruppin carefully considered his discussions with German-Jewish immigrants in Cyprus, as well as the economic and political realities on the ground. He argued that a large-scale German-Jewish community on the island could not be sustainable, as Cyprus lacked established Jewish and European communities. Additionally, he noted that an increased German-Jewish presence could provoke reactions from the colonial government and the local population. Moreover, the low cost of living was expected to rise sharply if the demand for labour and land increased due to Jewish migration.

Lastly, Ruppin questioned the quality of land available for developing orchards, which the German Jews could rely on for their livelihood. Nevertheless, he did not rule out the possibility of directing a small number of Jews to Cyprus, given that the cost of living, land prices, and labour costs were significantly lower than in Mandatory Palestine at the time. Still, his primary focus remained on channeling the growing migratory movement toward Palestine.

In 1925, Cyprus was declared a British Crown colony, placing the island under the control of a Western power known for its liberal asylum policy. During the 1930s, Cyprus attracted hundreds of Jews, predominantly from German-speaking areas, who were not only looking for a safer place to settle temporarily with their families, but also hoping to obtain a visa to enter Mandatory Palestine.

The Nazi’s legislative ban of specific professional categories from the economic life of Germany in 1933 prompted the migration of at least 37,000 Jews. At that time, German Jews could reside temporarily in Cyprus as travelers by paying an insurance fee of 25 pounds. With tourist status, they were permitted to stay on the island up to three months while awaiting authorisation to continue their journey to Palestine.

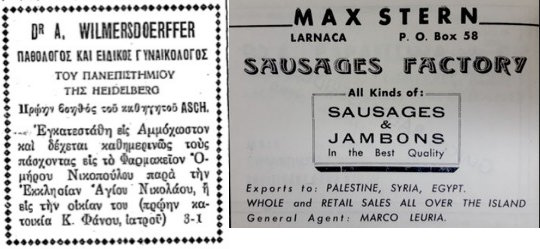

The settlement of German-speaking Jews in Cyprus (until 1938 mainly from Germany) began in 1933 and expanded over the following years, leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. As stated by Ruppin, in 1935, approximately 60 to 80 Jewish migrants lived in various towns of the island. Ruppin met with some of those immigrants, as mentioned in his report. Advertisements published in the local press announced the opening of medical clinics by German doctors. For instance, in July 1933, Dr. Erich Simenauer (1901–1988) from Berlin University, whom Ruppin mentions in his report, informed the Cypriot public that he had begun seeing patients daily at a clinic in a parish in Nicosia. Before settling in Cyprus, Simenauer had served as a surgeon and psychoanalyst at the Urban civil hospital and the gynecological clinic of the Charité hospital in Berlin. Similarly, in September 1933, Dr. Albert Wilmersdoerffer (?–?), a pathologist and specialist in gynecology from the University of Heidelberg, announced the opening of his medical office in Famagusta. In May 1933, Dr. Eduard Gogler (?–?), a surgeon-ophthalmologist from the University of Graz, opened a clinic on Nicosia’s main commercial road, Ledra Street. A year later, he moved his eye clinic to the upper floor of the Ford Agency and the Ottoman Bank building.

According to other sources, there were doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, engineers, electricians, artists, tradesmen, pensioners, and others among the German immigrants. They arrived at Cyprus’s ports with their families after a long and arduous journey, often passing through way stations in countries such as Switzerland, where they could secure visas to other destinations. Opportunities for certain professionals to earn a livelihood in Cyprus were limited. In October 1933, the colonial government amended the 1922 law on foreign missionaries, educational officers, and doctors, banning the issuance of professional licenses to foreign medical practitioners. This decision was based on the fact that Cyprus already had a disproportionately high number of registered doctors, making it difficult for them to sustain a living.

Fig. 2: Greek and English advertisements in local newspaper and commercial directory from the 1930s, promoting Wilmersdoerffer’s medical office in Famagusta and Stern’s sausage factory in Larnaca; Phone tis Kyprou, 09.09.1933 and Cyprus Commercial and Professional Directory 1946, Nicosia 1946.

Some immigrants lived off the money they had brought with them or by selling their personal belongings. Others established businesses in tourism and industry or found employment in large mining firms. In the early stages of settlement, migrant families often supported one another, exchanging services, such as washing clothes and sharing food. In Larnaca and Nicosia, German Jews opened a grocery store and a delicatessen. For example, Max Stern’s (?–?) sausage factory, founded during this period, became a well-known and long-term successful enterprise in the town.

Another couple that settled in the early 1930s was that of Friedrich Adler (1878–1942) and his wife, Frieda Adler (1897–1968), from Hamburg. Friedrich Adler was a professor at the College of Arts in Hamburg and a synagogue architect. Frieda Adler, also an architect, graduated from the same college. While her husband kept a small flat in Hamburg and only visited Palestine and Cyprus regularly, she stayed with their daughter. Friedrich Adler was deported from Hamburg to Auschwitz in 1942, where he was murdered. Before his assassination, Frieda Adler operated her own pension for Jewish tourists in Platres, called The Spring Hotel. In 1937, she was employed as an architect in the Cyprus Asbestos Mines Company in the Troodos mountains.

Parallel to the immigration of individuals, business migrants who were not from German-speaking lands also attempted to establish settlements. Since 1933, the Cyprus-Palestine Plantations Company in Limassol was managed by the Zionist Simcha Ambache (1892–1973) from Cairo and the banker Abraham Hassidoff (1898–1979) from Jerusalem. Also, as mentioned by Ruppin, the Empire Dental Industry Ltd, owned by the Lithuanian-Jew Samuel Simon Bloom (1860–1941), operated in Larnaca, manufacturing false teeth. These enterprises took advantage of the low tariff policy adopted in the 1930s within the British Empire to relocate their businesses to Cyprus. Moreover, they could also provide employment for Jewish migrant laborers if needed.

Ruppin was accompanied on his trip to Cyprus by Dr. Wilhelm Zeev Bruenn (1884–1949), a physician and agricultural entrepreneur from the Province of Posen (today Poland), who had purchased a large estate of more than 7,000 dunams of land in the fertile plain of Eastern Cyprus, in a village of Kouklia. Since 1899, this large estate had been the property of the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) and formed part of a broader agricultural scheme for Jews fleeing Eastern Europe following the rise of antisemitism at the end of the nineteenth century.

Bruenn, a German agriculturist who had settled in Hadera south of Haifa, established the Cyprus Farming Company Ltd in 1934. The company aimed to develop and sell land to German-Jewish individuals with a middle-class background. As stated in Ruppin’s report, two Jews from Gross Gaglow (today a district of Cottbus, Germany) whose property was expropriated by the Nazi government, visited the land seeking settlement either in Cyprus or Palestine. However, the scheme was not supported by Zionist circles and did not materialize as initially planned due to a lack of funding, the British immigration restrictions, and the uncontrolled purchase of land by foreigners. In 1938, Erich Popper (?–?), a Jew from Germany, acquired five plots of land at the price of 500 pounds each, according to the existing law.

Still, the number of German Jews in Cyprus continued to grow a couple of years after Ruppin’s visit. In December 1936, the British colonial government introduced a restrictive immigration law in response to the rising number of Jewish immigrants seeking refuge in Cyprus. The law aimed to control the massive influx of Jews from Nazi Germany. Consequently, those immigrants who got permission to settle on the island up to 1938 were required to have a minimum financial capital that enabled them to start a business and become self-sufficient. According to colonial reports, 240 Germans and 152 Austrians entered Cyprus between 1 April and 30 September 1938. Of these, 37 Germans and 90 Austrians remained on the island, and only 13 were granted a settlement permit.

However, the majority arrived in the period between September 1938 and March 1939 following the annexation of Austria, the military occupation of Czechoslovakia, and the November pogroms. From a total of 1,136 immigrants from Eastern and Central Europe who disembarked at the ports of Cyprus, the bulk originated from Germany. Specifically, 586 traveled from Germany and 458 from Austria, with the rest coming from Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Poland. In total, 480 bona fide Jews from Germany and Austria were granted a residence permit on the island by the colonial government. The majority settled in the major towns of the island, such as Nicosia, Larnaca, and Limassol, a few in rural Famagusta, and the rest in inland areas.

In May 1941, a month before the evacuation of the Jewish population from the island amid the fears of a Nazi invasion, the local Jewish community reported to the Colonial Secretary the number of Jews residing on the island. It was stated that out of 460 Jews, 163 originated from Austria (including 22 children) and the other 92 from Germany (including nine children). The rest were nationals of various countries, including Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the UK, the USA, and Mandatory Palestine. Among them was a well-known Jew in Cyprus, Elsie Slonim (1917–2021), who held an American passport even though she was raised in Austria. In 1941, the population was evacuated to Palestine and other destinations within the spheres of British influence, including Tanganyika (today Tanzania); eventually, very few returned.

Arthur Ruppin’s report illustrates the importance of Cyprus as a transit point for German-Jewish immigrants en route to Palestine, beginning with the early stages of Nazi expulsion. In this regard, it highlights the significance of British colonial territories, such as Cyprus, in the path of this group to Mandatory Palestine during the turbulent interwar years. The role of geography and political context, such as the proximity of Cyprus to Palestine and British colonial governance, was a key factor in promoting a German-Jewish trans-Mediterranean migratory network.

The report also offers a glimpse into the German-Jewish presence on the island during the 1930s. Of course, a robust Jewish community was not encouraged at that point. As Ruppin emphasized in his report, the migratory flow should not be facilitated, as it could pose a threat to the Zionist cause of establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Yet, only a few years after Ruppin’s remarks, and just before the outbreak of the Second World War, Cyprus attracted hundreds of immigrants from German-speaking areas, providing both security, accommodation, and employment. The absence of strong Zionist support for such a scheme ultimately prevented many of them from staying in Cyprus.

Cyprus State Archives, Secretariat Archives: SA1/791/1938, SA1/1208/1938, SA1/670/1941, SA1/730/1941.

Cyprus Gazettes 1933–1934 accessible via Cyprus Digital Library: http://www.cyprusdigitallibrary.org.cy

Newspapers Cyprus Mail and Phone tis Kyprou accessible via the Press and Information Office digital archive (PIO): https://pressarchive.cy

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Evangelia Matthopoulou holds a Ph.D. in Modern and Contemporary History from the University of Cyprus (2016) and an MA in History of International Relations from the London School of Economics (2008). Her Ph.D. thesis elaborated the history of Jewish presence in British Cyprus from 1878 to 1959 with emphasis on the migratory wave of European Jews in Cyprus, their economic impact on the island, and their business activities. She has published several papers in peer-reviewed journals and edited volumes. Since 2016, Matthopoulou has been affiliated as a Special Scientist at the University of Cyprus, teaching the undergraduate course “Economy and Colonialism” at the Department of History and Archaeology. From 2019 to 2021, she pursued post-doctoral research at the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation (POST-DOC/0916/0231). She is currently a Special Scientist for Research at the Archaeological Research Unit of the University of Cyprus (EXCELLENCE/0524/0252). Her research interests lie in the history of migration, colonial business history and enterprises, and the history of migratory and business networks in the Eastern Mediterranean basin.

Evangelia Matthopoulou, A Glimpse into the German-Jewish Presence in Cyprus during the 1930s: Reflections on Arthur Ruppin’s 1935 Report, in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, August 19, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-34> [February 23, 2026].