Born 15 June 1903 in Tuzla, Austria-Hungary (today Bosnia-Herzegovina)

Died on

20 December 1999 in Vienna,

Austria

Occupation: Art historian, professor, housekeeper, tourist

guide

Migration: Egypt, 1936 | Austria, 1947 | Egypt, 1947 | Austria, 1968 | Canada, 1970 | Austria, 1974

“By now I have understood that the longing for past times, lost places, is nothing more than the longing for oneself, for that happy self, one once was.” Hilde Zaloscer, Eine Heimkehr gibt es nicht. Ein österreichisches curriculum vitae, Wien: Löcker Verlag, 1988, 11 (Translation provided by the author). Throughout her life, the Austrian art historian Hilde Zaloscer struggled with feelings of having lost her home and the wish to return to the places that had been taken from her through displacement and flight. Two years before the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, she found a new home in Egyptian exile and only reluctantly returned to Vienna in 1968. Despite remaining connected to German-speaking culture, Zaloscer felt like a stranger in Austria after her time in exile and mourned her expulsion from Egypt until her death.

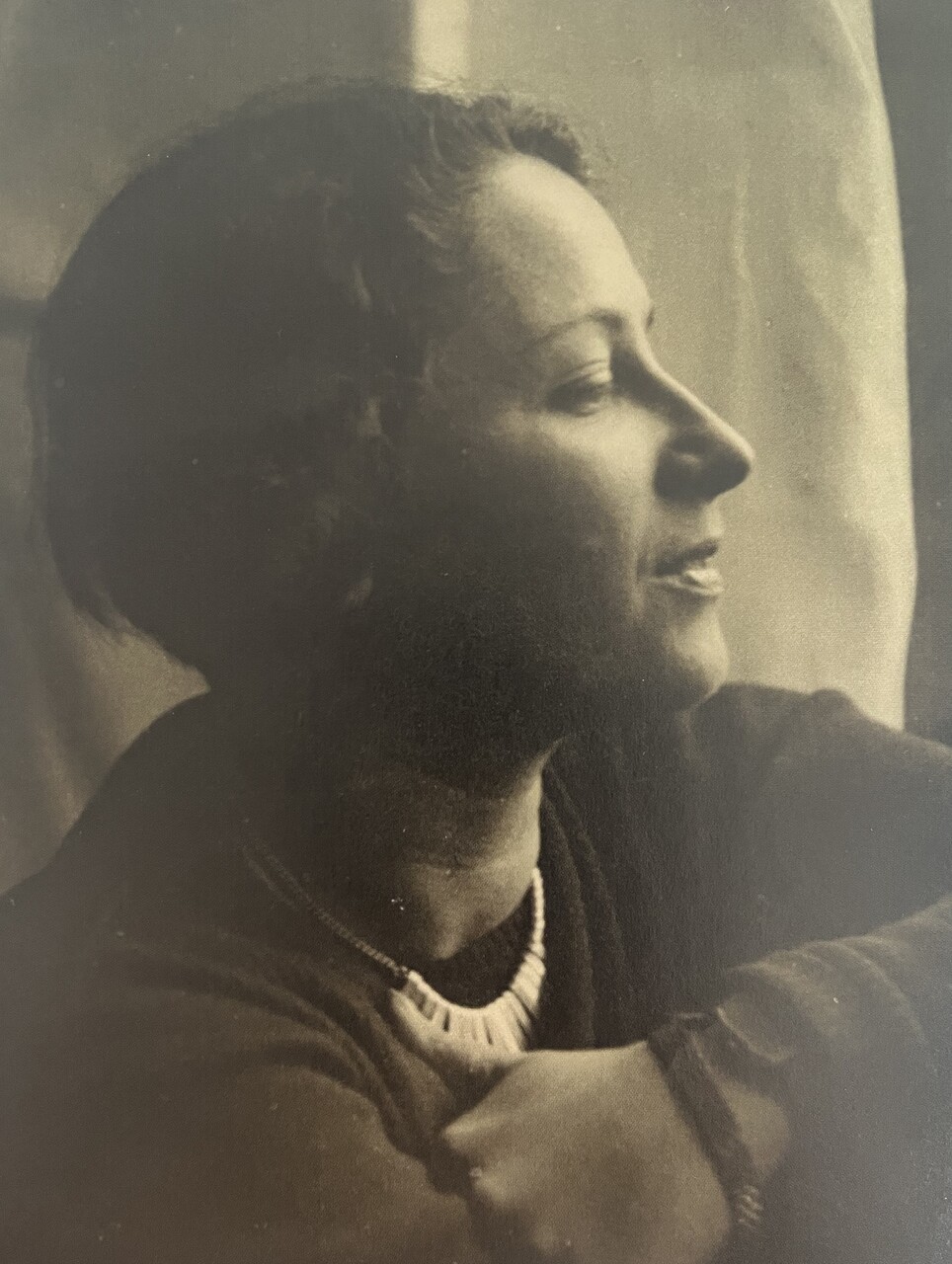

Fig. 1: Portrait of Hilde Zaloscer in Egypt, around 1940; estate of Hilde Zaloscer, Institute Vienna Circle, John Sailer private archive.

Hilde Zaloscer was born in Tuzla in 1903 as one of three children of a wealthy Jewish family that belonged to the middle class. Zaloscer spent her childhood in Tuzla and Banja Luka, which both belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the end of the First World War. Her father, Jacob Zaloscer (1869–1951), worked as an administrative lawyer for the Danubian monarchy; her mother, Bertha Zaloscer née Kallach (1881–1939), was a pianist. According to Zaloscer’s autobiography, which was published in Vienna in 1988, neither politics nor religion were discussed in her family, and she only became aware of her Jewish ancestry when she grew older. Instead, the family spoke German and English at home and emphasized to their children the importance of reading literary classics by German and French authors. The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918 brought a sudden end to Zaloscer’s sheltered childhood: the family had to leave Bosnia abruptly, which became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and was forced to start a new life in Vienna.

Fig. 2: Hilde Zaloscer (right) and her younger sister Erna around 1911, photo by Johann Patzelt; estate of Hilde Zaloscer, Institute Vienna Circle, John Sailer private archive.

In Vienna, Zaloscer finished secondary school and enrolled in the art history program at the University of Vienna in 1921. The 1920s in Vienna were characterized by political turmoil and violent conflicts between parties on both sides of the political spectrum. Zaloscer became aware of the increasing polarization and rise in antisemitism only after she finished school with her dissertation in 1927. She struggled to find work in Austria because Jews were increasingly ostracized from the job market. While Zaloscer found employment as an editor with the art magazine Belvedere after a while, this position confronted her with her colleagues’ antisemitism on the regular. Even though she sought further training as a bookbinder, interior designer, and a specialist in repress techniques, her prospects for a future in Vienna continued to worsen, eventually forcing her to emigrate at the beginning of the 1930s.

In 1936, Zaloscer received the opportunity to work as a housekeeper in Alexandria. This position did not match her qualifications, and she did not know what life in Egypt would be like. But starting a new life there seemed more promising than her outlooks in Vienna. Emigrating as a domestic servant offered many, mostly Jewish women, the opportunity to leave their home countries. Still, it also involved entering into a precarious dependency with one’s employer, as Zaloscer’s case shows.

In August of 1936, Zaloscer started her new position as Dr. Ahmed el-Nakeeb’s (?–?) housekeeper, who served as the director of the Al-Moassat hospital in Alexandria. Zaloscer quickly adapted to her new occupation and oversaw the coordination of the other house servants. Due to the fact that Egyptian society had been shaped by British colonialism, she soon ran into problems with the family, as it was highly unusual at this time that Europeans worked for Egyptians. Ultimately, it was not cultural differences that led Zaloscer to quit her job as a housekeeper after only five months. According to Zaloscer, her employer’s wife harassed her out of jealousy and forced her to quit.

Without any savings or the prospect of a new job, Zaloscer took a great risk by leaving her position. She did not want to leave Egypt so soon again because, after only a short time there, she had fallen for the country and was incredibly fascinated by the foreign culture. After she quit her job as a housekeeper, Zaloscer started earning her living as a tourist guide and author.

Shortly after arriving in Alexandria, Zaloscer was able to get in touch with the local branch of the Association of Academic Women, which also helped her find a new accommodation after quitting her housekeeping job. Zaloscer had already joined this association in Vienna, which was founded at the beginning of the twentieth century in London and was well-connected internationally. By joining several more clubs, Zaloscer was introduced to other emigrants and expanded her social network and job prospects in Egypt. “If you knew an émigré”, as Zaloscer recalled, “you were passed around, met others, and were gradually integrated into the émigré colony.” Hilde Zaloscer, “Das Dreimalige Exil,“ in: Friedrich Stadler (ed.), Vertriebene Vernunft: Emigration und Exil österreichischer Wissenschaft 1930–1940, vol. 1, Wien: Jugend & Volk, 1987, 544–572, 554 (Translation provided by the author).

Fig. 3: Hilde Zaloscer during a trip to Kitchener’s Island in Egypt, undated; estate of Hilde Zaloscer. Austrian Archive for Exile Studies at the Literaturhaus Wien, John Sailer private archive.

Zaloscer primarily associated herself with the larger German and French exile communities since the number of emigrants from Austria during this time remained rather small. She started giving talks at the Atelier, Groupement des Artistes, and was a member of the learned societies Société Royale d’Archéologie and Société d’Archéologie Copte, which were founded in Alexandria in 1893 and Cairo in 1934, respectively. Belonging to these communities instilled new confidence in Zaloscer and made her feel more at home in Egypt. Nevertheless, she was also very critical of these closed European circles because she observed that they had initially inhibited her from seeing the effects of colonialism and the discrimination against the Egyptian population. Egypt, which had been under British control since 1882, became nominally independent in 1922. However, until gaining full independence, it remained under the ‘protection’ of the British Empire. In later years, Zaloscer became very vocal about the fact that Egyptians were systematically denied high-ranking positions and that they did not receive the same access to education as Europeans in the country did.

Even before the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938, Zaloscer’s family strongly discouraged her from coming back to Vienna, which soon led her to reject the idea of return entirely and made her accept the idea of living in exile in Egypt permanently. Before the Second World War broke out, Zaloscer’s family managed to flee Austria, and in the summer of 1939, Zaloscer was able to meet up with her father and her sister Erna Zaloscer (1908–2004) in Paris. Zaloscer’s mother had passed shortly after the family’s successful escape, and her other sister had fled to Yugoslavia.

When Zaloscer returned from Paris, she was again confronted with an uncertain future. Her main source of income – the archeological and art history excursions – had become all but impossible as a result of the war. Furthermore, as an Austrian citizen, Zaloscer was declared an enemy alien in Egypt. To avoid being detained or possibly deported back to Austria, Zaloscer decided to enter a marriage of convenience with an Egyptian man to attain Egyptian citizenship.

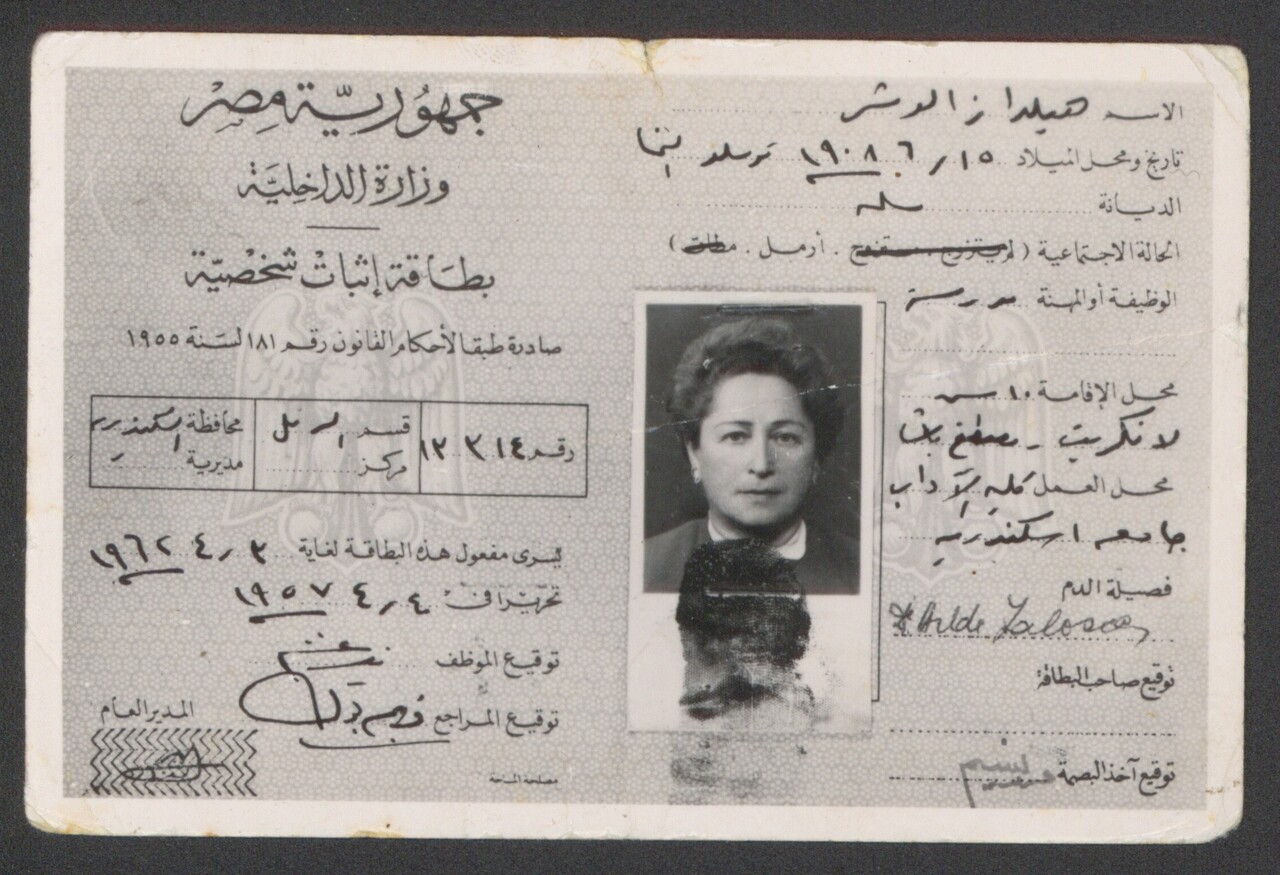

Fig. 4: Hilde Zaloscer’s passport during her time in Egyptian exile; estate of Hilde Zaloscer, Austrian Archive for Exile Studies at the Literaturhaus Wien, John Sailer private archive.

Marriages of convenience played an important role in protecting Jews from Nazi persecution and discrimination not just in exile. In some cases, they were even arranged by institutions such as the Jewish hospital in Alexandria. In Zaloscer’s case, a couple of friends put her in touch with an Egyptian factory employee, who agreed to marry her and secure her stay in the country in exchange for 50 pounds. Zaloscer adopted the name ‘Samira Shukri’ and formally converted to Islam during the ceremony. She did not keep in touch with her husband after the wedding and had to learn from a friend shortly afterwards that she had become a widow. For Zaloscer, the marriage was a purely pragmatic means to ensure that she could stay in Egypt, and she did not feel any obligation towards her Egyptian husband or Islam.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Egypt declared itself neutral. However, it soon became a target of German and Italian attacks because it played a crucial strategic role as an Allied military base in the Eastern Mediterranean. As a result thereof, Zaloscer began witnessing the first bombings of Alexandria in June of 1940. During the war, she became acquainted with members of the Jewish Brigade whom she met through a Jewish soldiers’ club. Talking to these soldiers, who had formed their own unit within the British Army in 1944, Zaloscer heard the first reports about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943 and began to fear the prospect of falling into the hands of the German Army. After the end of the war, Zaloscer was able to gather information about her family’s whereabouts – most of whom had managed to flee to the United States. Even her youngest sister, Ruth Zaloscer (1911–1998), who had been deported to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, had survived.

After her father and her sister had returned to Vienna in 1947, Zaloscer longed to be reunited with them and decided to start a new life in Vienna. She returned in hopes of now having better prospects there and not encountering the same level of antisemitism as before the war. However, Zaloscer quickly found herself disappointed by what she found in Vienna: instead of a clean slate, the situation had not improved much, and many ex-Nazis occupied important positions in the country. Zaloscer was enraged by the lack of willingness to grapple with the recent past and returned to Egypt that same year.

When Zaloscer returned to Alexandria at the end of the 1940s, her situation there improved dramatically. Her acquaintance, the renowned Egyptian writer Taha Hussein (1889–1973), had been named minister of education and appointed her to a professorship of art history at the University in Alexandria. Receiving this appointment marked a caesura in Zaloscer’s relationship with Egypt because she ceased to see the country as her exile and instead started thinking of it as her home. Her perception of herself changed as well. She no longer saw herself as “an emigrant in emigrant circles, but [as] an Egyptian official working at an Egyptian university with Egyptian colleagues and Egyptian students.” Hilde Zaloscer, Heimkehr, 124 (Translation provided by the author).

Fig. 5: Hilde Zaloscer (seated front left) with her students in Alexandria, around 1965; estate of Hilde Zaloscer, Institute Vienna Circle, John Sailer private archive.

More than ten years after she had first come to Egypt, Zaloscer felt like she had arrived and no longer had to worry about her livelihood. Looking back on the years between 1950 and her later escape from Egypt, she described this time as the happiest period in her life. However, Zaloscer soon realized that the country, which had gained independence in 1936, was undergoing massive changes and that the political situation had become highly volatile. Egypt had lost several wars against the State of Israel, which was founded in 1948, and saw an awakening of nationalist sentiments, which both gave rise to antisemitism and xenophobia in the country. Already in the 1930s, the Muslim Brotherhood had stoked antisemitic resentments. Zaloscer frequently found herself victimized by these attitudes, was accused of being a spy several times, and was openly attacked on the street.

After the end of the Six-Day War in 1967, the situation for Jews in Egypt worsened again dramatically. Jewish financial assets were confiscated, and male Jews between the ages of 16 and 60 were detained. An estimated 80,000 to 85,000 lived in Egypt in 1927. Only around 2,500 Jews remained in the country by the end of the Six-Day War, as a result of the Arab-Israeli wars and the subsequent repressions, which triggered several emigration waves.

Zaloscer herself was brought in for questioning by the police repeatedly and then put under house arrest. The professor began fearing for her safety and started planning her escape from Egypt. However, the Egyptian citizenship that had guaranteed her protection during the Second World War posed a problem now. As an Egyptian by law, Zaloscer needed an exit visa to leave the country. This visa was difficult to attain, and Zaloscer only managed to get a two-week visitor visa to see her family in Vienna by soliciting the help of an acquaintance. At this time, Zaloscer already knew that she would not return to Egypt and said her final goodbyes to Alexandria in August of 1968.

Fig. 6: Hilde Zaloscer in Vienna, undated; Hilde Zaloscer estate, Institute Vienna Circle, John Sailer private archive.

At the age of 65, Zaloscer returned to Vienna – a city she no longer considered to be her home but her new exile. She felt like a stranger in Vienna and became severely depressed because she was unable to find a new job and found herself in a precarious financial situation. When Zaloscer was offered a position as visiting professor in Ottawa, she left Vienna again in 1970 for another four years.

Even though Zaloscer retained a connection to German-speaking culture and specifically valued the works of German writers throughout her life, she felt more at home in Egypt, where she had survived the Second World War as a Jew, than she ever did in Austria. This explains why she delayed her escape from Egypt as long as possible and why she chose to remain in Alexandria, even when the majority of Jews had already left the country.

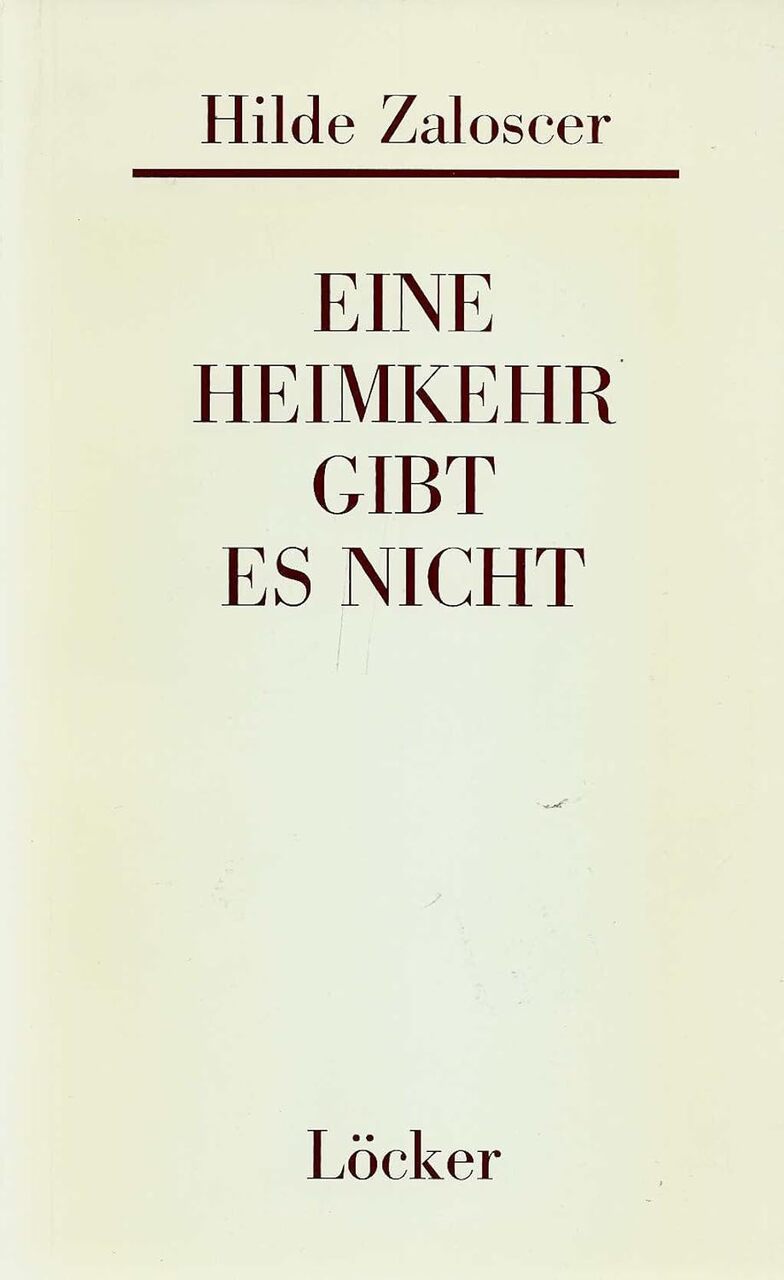

Fig. 7: Hilde Zaloscer’s memoirs, published in 1988 by Löcker in Vienna.

For Zaloscer, being displaced multiple times throughout her life constituted a traumatic caesura, which she reflected in the title of her autobiography Eine Heimkehr gibt es nicht (1988) – There is no Return Home. It was published at a time when the Austrian public was beginning to engage more intensively with the National Socialist era for the first time. The experience of exile became a key moment for defining herself and her academic oeuvre. Hilde Zaloscer died in Vienna in 1999 at the age of 96.

Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance (DÖW), Vienna, collection “Erzählte Geschichte,“ interview no. 416.

Literature by and about Hilde Zaloscer in the catalogue of the German National Library: https://portal.dnb.de/opac.htm?method=simpleSearch&query=119114461

Memorial for the persecuted, displaced, and murdered at the Institute of Art History at the University of Vienna, entry for Hilde Zaloscer:

https://geschichtegesichtet.univie.ac.at/h_zaloscer.html

Exhibition Persecuted. Engaged. Married: Marriages of Convenience in Exile, Jewish Museum Vienna. The curators Irene Messinger and Sabine Bergler explain how a marriage of convenience became a survival strategy for Hilde Zaloscer, 2018:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Anna Günter received her BA in British and American Studies and History at Bielefeld University. In 2023, she finished her MA in History at Missouri State University with a thesis on the acts of revenge and revenge fantasies of Jewish Holocaust survivors in postwar Vienna, which received the Missouri State University Distinguished Thesis Award in the Humanities category. Her essay “The 1931 Biatorbágh Train Attack as an Example of Political Polarization of Austrian Newspapers in the Interwar Period” won the Journal of Austrian Studies Graduate Student Essay Prize in 2024. For the eightieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War, zeitgeschichte|online published her essay on Jewish revenge as a critical tool for the discussion of memory politics. Starting in the fall of 2025, she was accepted into the PhD program in History at Northwestern University.

Anna Günter, Hilde Zaloscer (1903–1999), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, June 18, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-30> [February 03, 2026].