The history of Jewish immigration to New Zealand is closely linked to the larger history of European settlement on the two main islands of this South Pacific archipelago. In 1838, the Jewish merchants Joseph Barrow Montefiore (1803–1893) and Joel Samuel Polack (1807–1882) called upon the British House of Lords to support the colonization of New Zealand. They viewed the small archipelago as a paradise, considering its landscape, fertility, and climate to be absolutely ‘perfect.’ The extended Montefiore family, Sephardic Jews rooted in Italy and England, had been linked to the Frankfurt-based Rothschild banking dynasty since 1815 by the marriage of Abraham Montefiore (1788–1824) to Henriette Rothschild (1791–1866). The Montefiores invested in the planned settlement of New Zealand and supported numerous Jews of German origin in the process.

As the refuge in the (post-)colonial world farthest away from Central Europe, New Zealand occupies a unique place in the history of German-Jewish migration and diaspora. Trade and travel hinged on trans-cultural channels of communication across vast distances and required remarkable mobility and multilingualism. These trade connections often centered on ties between extended families, neighbors, and Jewish communities. Networks founded in the nineteenth century supported migration chains that, though modest in scale, were often vital to survival. Between 1938 and 1939, these connections proved crucial to those persecuted by the Nazi regime, whose chances of emigration from Germany and the annexed countries were growing ever slimmer. This complex web of connections remained a defining feature of the German-speaking Jewish community in New Zealand across all generations.

It also shaped the community’s good relations with the Māori, the tangata whenua or Indigenous people of Aotearoa/New Zealand. In the nineteenth century, some Māori groups saw themselves as descendants of one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, even referring to themselves as “huria” (transliteration for Jews) in the ‘furthest Promised Land.’

The systematic colonization of New Zealand by the British Crown began in 1840, a process carried out by the New Zealand Company and often supported by Jewish mercantile families. In Germany, the Hamburg-based agencies J.C. Godeffroy & Sohn and John N. Beit administered the colonization program of the trading company, which was active in New Zealand from 1825 to 1858. The main European ports of departure for the five-month sea voyage were London, Hamburg, Bremen, and Rotterdam, though passengers could also board in Sydney or Melbourne.

On the whole, German-speaking Jewish immigration during the colonial period between 1842 and 1899 consisted largely of chain migrations involving groups of three to twelve individuals. The first immigrants in a group were often joined later by some of their relatives and neighbors. Most of the early German-speaking settlers in New Zealand were Jews of German origin who had already spent time in England or Australia and had engaged in business there. A second group were young men who, after the failure of the democratic revolution in Germany of 1848, sought political refuge in the ‘New World,’ where Jewish colonists were accepted as equal.

The most significant waves of migration occurred in the early years of European settlement (1842–1847) and during the New Zealand gold rush (1861–1867). Another wave followed between 1872 and 1886, supported by Prime Minister Julius Vogel (1835–1899), who held the high office until 1886. Vogel himself was Jewish and raised in London.

Overall, however, there were only a modest number of Jewish immigrants from German-speaking parts of Europe. By the outbreak of the First World War, only around 900 German-speaking Jews had settled in New Zealand, which had a total population of 1,089,825 at the time. The first group to arrive, before 1847, numbered just 22, while the last group before 1914 included 364 members of this demographic. Most came from Prussia and northern Germany, including cities such as Hamburg, Braunschweig, and the Prussian province of Posen. Throughout the period, male immigrants outnumbered female ones by far – even in urban areas, where the gender ratio around 1899 averaged 65 to 35.

The small, scarcely developed island territory of New Zealand, which had an Indigenous population of around 80,000 in 1840, posed tremendous challenges to the first generation of settlers, who endured the unfamiliar hardships of life in the dense rainforest and were faced with a harsh climate and persistent south winds from the Antarctic and some 170 rainy days per year.

On the North Island, German-speaking Jewish immigrants were drawn primarily to the commercial centers of Auckland and Wellington. Most were merchants or craftsmen from the twin port cities of Hamburg and Altona and the town of Barth on the Baltic coast. Small, owner-run tailoring shops, jewelry and clothing stores, as well as furniture makers and furriers, quickly developed into established businesses in Auckland’s Princes Street and Waterloo Quadrant and Wellington’s Willis Street. Early on, German-speaking Jews also settled in towns and settlements of the South Island such as Dunedin, Christchurch, Timaru, Oamaru, Nelson, and Thames.

Many acquired land or founded shipping agencies, skilfully leveraging their overseas contacts to export grain and wool to England and Germany. Importing food and spirits and exporting whale oil and whale bone also proved to be lucrative. Some firms evolved into veritable business dynasties, such as the extended Hallenstein/Michaelis/Theomin family in Dunedin.

Fig. 1: Bendix Hallenstein (seated at the center) with his family, around 1890; Dunedin Public Libraries.

After building the Brunswick Flour Mill in Otago, the country’s first inland grain mill, Bendix Hallenstein (1835–1905) went on to found New Zealand’s first clothing factory in 1873. Within a decade, its staff grew to three hundred. By the turn of the century, there were thirty-four Hallenstein stores nationwide.

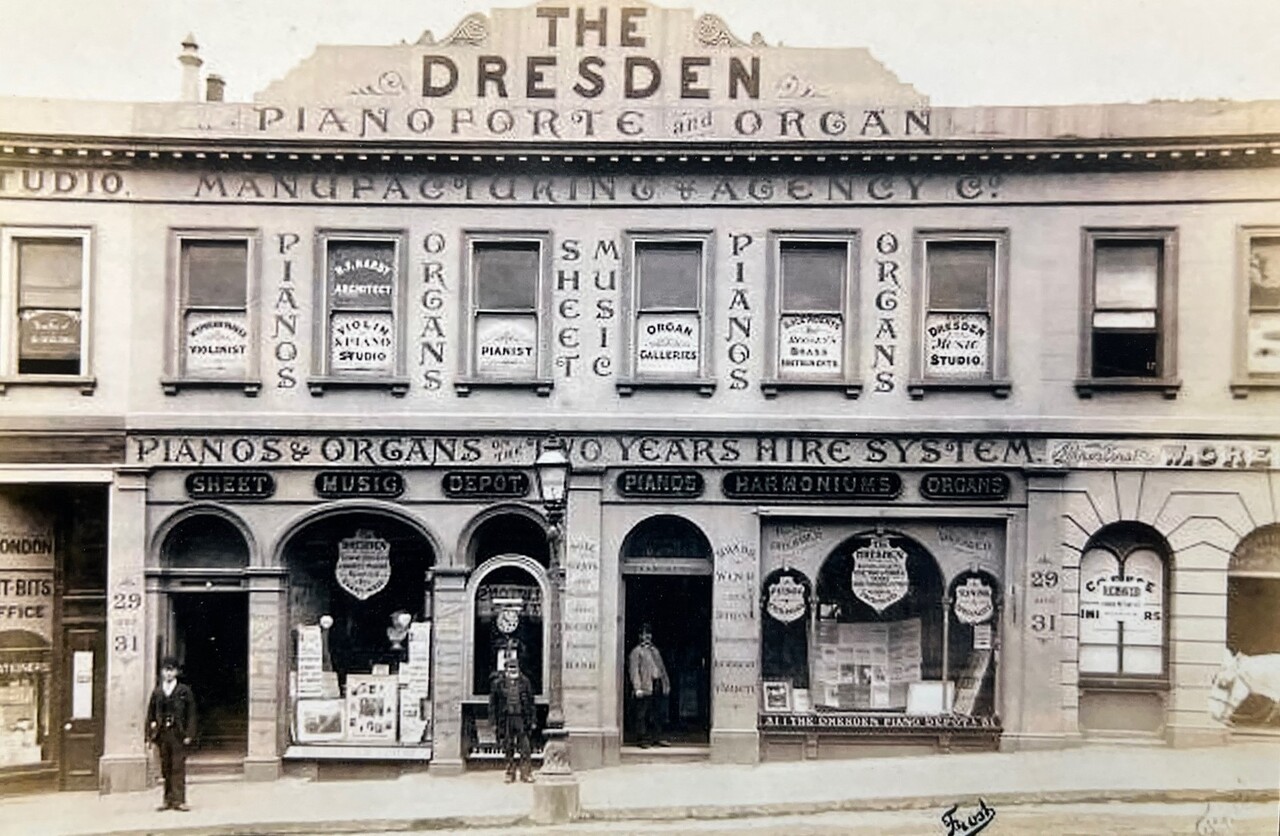

The tanning industry and the leather trade were also predominantly Jewish. The Hallenstein business empire soon expanded into tanning, and Bendix was joined in 1885 by his cousin from Melbourne, Moritz Michaelis (1820–1902), who had been born in Hanover. Michaelis’s son-in-law, David Ezekiel Benjamin – later known as David Edward Theomin (1852–1933) – contributed to the development of the tannery business and became the leading supplier of musical instruments in New Zealand as the proprietor of the Dresden Pianoforte Manufacturing Company, founded in 1883.

Fig. 2: David Theomin’s Dresden Pianoforte Manufacturing Company, founded in 1883, Dunedin; Dunedin Public Libraries.

Transnational connections with Jewish merchants and traders in Australia, England, and Germany were essential to the commercial success of Jewish immigrants in New Zealand. The Hallenstein-Michaelis-Theomin family is one of many extended families that maintained and expanded their overseas networks with energetic enterprise.

As members of a small Jewish community, the German-speaking settlers knew each other well, supported one another, and often had family ties. In the year 1843, ten male members gathered for the first time to form a minyan in Auckland, and a small group celebrated the first Passover in the Wellington home of the German carpenter Johann Levien (1811–1871). With a few exceptions – such as Rabbi Bernard Lichtenstein (1843–1892), who was born in the Neustadt district of West Prussia – the leadership of the Jewish community remained entirely in the hands of Anglo-Jews. Dietary laws were loosely observed, given the difficulty of preparing kosher meat according to ritual standards, and Shabbat services were only an hour long so that the merchants could return to work.

As in most colonial Jewish communities, the first priority was to establish a cemetery, followed by acquiring a building to serve as a permanent house of worship. When gold was discovered in Otago and on the West Coast in the 1860s, the Jewish population rose to around 1,200, and synagogues were built across the country. New prayer spaces were established for newcomers – including more than a hundred from the German-speaking world – even in remote and inhospitable locations such as Hokitika, situated on the South Island’s storm-battered West Coast. On the High Holidays, the Hokitika Synagogue on Tancred Street became a gathering place for Jews from across the West Coast, which is 600 kilometers long.

The world’s southernmost German-speaking Jewish diaspora also flourished in Dunedin. In 1860, only five Jewish families lived there, including that of the wholesaler Adolf Bing (?–1870), born in Altona, and that of Yiddish-speaking Wolf Harris (1833–1926), born in Kraków. The first brick building in Dunedin was built to house their import firm Bing, Harris & Co. After prospectors struck gold in Tuapeka in 1865, the Jewish community expanded so rapidly that by 1878 it had grown to 428 members, including around fifty German-speaking families, and a six-hundred-seat synagogue was built.

In a settler society, buildings and institutions serve as an important expression of a community’s identity. The grand synagogue in colonial Dunedin was thus seen as a symbol of Jews’ equality among the newly arrived Europeans in New Zealand. At the time, 80 percent of Dunedin’s Jews were merchants, and the influx of German-speaking community members under Julius Vogel’s assisted migration program, introduced in 1872, was strongly supported by the Hallenstein-Michaelis-Theomin business dynasty. In the absence of other Jewish associations or social institutions, Jewish communal life revolved entirely around the synagogue until the end of the nineteenth century. The small number of German-speaking Jews tried to maintain certain traditions of neo-Orthodox Judaism within the broader Anglophone community.

That the German-speaking Jewry flourished so quickly after their arrival in New Zealand was not only thanks to their members’ resourcefulness and perseverance. Their philanthropy, aligned with the Jewish principle of tsedakah, earned them the respect of their English-speaking neighbors. New Zealand’s egalitarian culture – with its emphasis on fairness, consensus, and cooperation – facilitated the rapid social integration of Jewish immigrants. They joined the same horse racing clubs and yacht clubs as the predominantly Protestant colonists, and many Jewish merchants entered occasional business partnerships with Christians. Owing to the small number of women among the first cohorts of settlers, interfaith marriages were not uncommon – though mixed families usually maintained ties to the Jewish community. In addition, the colonial period saw strong identifications between Jews and Māori. Around the mid-nineteenth century, Te Ua Haumēne (1820–1866), leader of a syncretic religious movement known as Hauhauism, even claimed that Māori were huria, one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. This belief worked to the Jewish settlers’ advantage: during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s, Haumēne’s followers spared their lives, regarding them as ‘distant relatives’.

Economic success and the opportunity to participate in the social, political, and cultural life of the British Dominion gave Jewish immigrants a sense of security and belonging. Jews could hold public office and take part in both municipal and national politics. In this regard, they were considered equal to their fellow New Zealanders of European origin, known as “Pākehā.”

For instance, the Member of Parliament Samuel Edward Shrimski (1828–1902), who was born in Posen, Prussia, introduced the Education Act of 1877, abolishing denominational schooling and creating today’s system of free, secular, and compulsory education. Businesspeople such as the Hallenstein-Theomin family in Dunedin and Gustav Kronfeld in Auckland became known nationwide as patrons and sponsors of cultural activities. David Edward Theomin’s mansion in Dunedin, called Olveston, and Kronfeld’s home in Auckland, Oli Ula, became popular gathering places for discussions, readings, and musical performances. As social and intellectual centers, these residences fostered a sense of belonging to the German-Jewish diasporic community through exchange and conviviality.

After arriving in New Zealand, German-speaking Jewish immigrants had to naturalize as British subjects. English was the official language, while German remained confined to the private sphere of family and close friends. Even though they did not develop a unified diasporic culture with their own German-language associations and periodicals, German-speaking Jews formed a self-assured subgroup of the Anglophone Jewish community. Following the wave of naturalizations around the turn of the century, German speakers made up a quarter of the entire Jewish population of New Zealand, which stood at 1,611 in 1900. Jews thus represented 0.2 percent of the total population.

Many families maintained ties with their countries of origin, underlining the transcontinental dimension of this small diasporic community and its various networks. Valuing both education and family bonds, they often sent their children – who were fluent in German – to universities in Germany.

The German-speaking Jewish immigrants of the nineteenth century were driven above all by the hope of improving their social and economic situation. While the early years of settlement were marked by a hard struggle for existence, the remote Dominion of the British Empire also offered greater social mobility. During the First World War, however, German-speaking Jewish settlers came under growing pressure. They were considered politically suspect, placed under surveillance, and in some cases interned as ‘enemy aliens’. A parallel development occurred during the Second World War, when a new group of German-speaking Jews moved into the public spotlight. The influx of refugees brought the German-speaking Jewish community to its historical peak in both numbers and, arguably, cultural influence.

As the situation of the Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe became increasingly desperate following the Anschluss, or annexation, of Austria in 1938, many began to consider even the farthest countries overseas as potential destinations to escape to. Among them was New Zealand – a destination that the philosopher Karl Popper (1902–1994) described from a European perspective as: “not quite the moon, but after the moon it is the farthest place in the world.” As quoted in James Kierstead, “Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies, and Its Enemies,” The Journal of New Zealand Studies, no. NS28 (2019): 4, https://doi.org/10.26686/jnzs.v0iNS28.5418. Refugees often explained their decision to flee to New Zealand by saying they wanted to go as far away as possible. Their family history played a significant role in these decisions. For the Berlin-born actress Minnie Kronfeld (1904–1987), later known as Maria Dronke, the ‘choice’ of New Zealand was influenced by the adventurous tales of her ancestor Gustav Kronfeld.

However, sparsely populated New Zealand – which had 1,573,812 inhabitants according to the 1936 census – was not particularly inclined to take in refugees from Nazi Germany and the territories it later occupied. The Immigration Restriction Act of 1920 had already imposed severe limitations on immigrants of non-British origin. Unlike the United States or Australia, New Zealand had no official quotas for the admission of European refugees. Immigration regulations included stipulations that foreign immigrants had to present ‘landing money’ in the amount of 200 British pounds. In addition, a New Zealand citizen or organization had to guarantee that the newcomer would not become a financial burden on the state and that they would swiftly integrate into the labor market.

As with Australia, refugees needed the right connections to go to New Zealand, given the immense distances and restrictive immigration laws. These contacts were often provided by the German-speaking Jewish community and charitable organizations, including the New Zealand branch of the Australian Jewish Welfare Society and the Wellington Hebrew Philanthropic Society, founded in 1940. The Jewish community in Dunedin played a key role in this context, especially as figures like Hallenstein and Theomin had been instrumental in building up the German-speaking Jewish diaspora locally. Hallenstein’s son-in-law, Willi Fels (1858–1946), founded the Christchurch Refugees’ Emergency Committee on the South Island together with Karl Popper, quoted above, and the geneticist Otto Frankel (1900–1998). From 1938 to 1940, this committee operated out of Christchurch and Dunedin, actively campaigning for the admission of refugees. By 1940, the Dunedin Jewish community had 250 members, 160 of whom came from Germany and Austria.

Around 1,100 refugees – that is, one for every 1,500 residents – succeeded in obtaining a visa to enter New Zealand, although the authorities received applications from at least ten times that number. Despite the restrictive immigration policy, which favored farmers, artisans, and technicians, most refugees worked in independent professions such as medicine, law, or trade. They were mostly young men, although some couples and young families also immigrated. Well-known personalities were the exception. In addition to Karl Popper, notable examples include the poet Karl Wolfskehl (1869–1948) and the architects Ernst Plischke (1903–1992) from Austria and Henry Kulka (1900–1971) from Czechoslovakia.

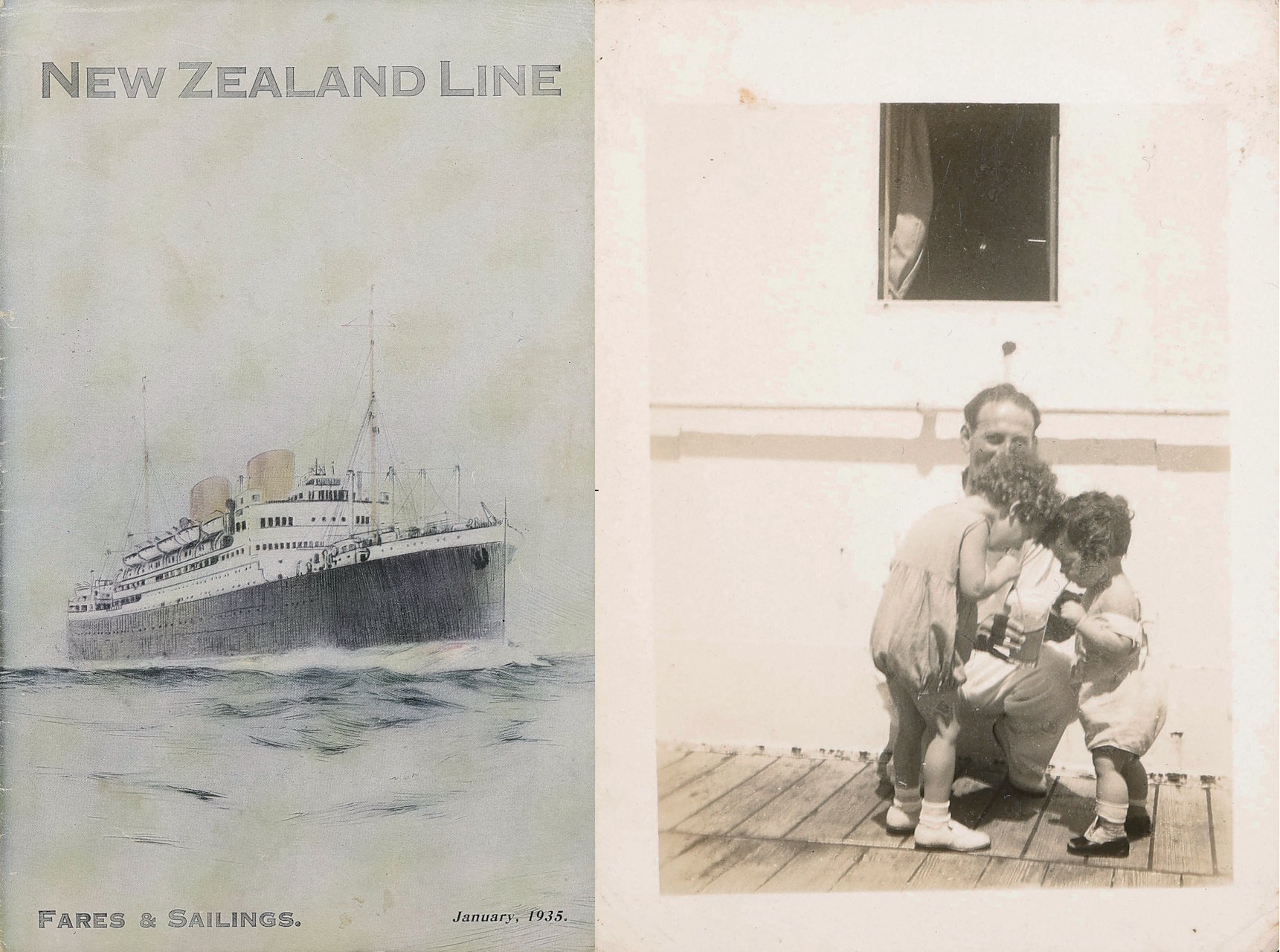

Many families used their diasporic networks to reach these far-flung Pacific islands. They typically obtained a transit visa for the United Kingdom and then embarked for New Zealand from London. The voyage usually lasted nine weeks and often passed through Tangier, Bombay, Colombo, and Sydney before reaching Wellington or Auckland.

Fig. 3 and 4: New Zealand Line, brochure printed in English, January 1935; Jewish Museum Berlin, inv. no. 2015/14/232; Georg Lemchen with his daughters Hannah Beate and Susanna Renate on the ship to New Zealand, May 1935; Jewish Museum Berlin, inv. no. 2015/14/263. Donated by Hannah Templeton, Susi Williams, and Barbara Cole. Digitization funded by the Adler-Salomon family, Siemens AG, the Berthold Leibinger Foundation, and Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA.

Most refugees had never even heard of the small island state in the South Pacific until they were forced to leave Europe. Their arrival in New Zealand’s cities often came as a culture shock. The style of the colonial buildings – small wooden houses with corrugated iron roofs and narrow shopping streets – was unfamiliar to them. The homes, typically heated by a single stove, felt makeshift and temporary.

New Zealand entered the war early, in September 1939. The many special regulations introduced after the outbreak of war made it even more difficult for refugees to begin new lives. In October 1940, all German-speaking refugees were classified as ‘enemy aliens.’ From then on, they were subject to mandatory registration, banned from public gatherings, and placed under official surveillance. They were prohibited from owning radios, cameras, maps, binoculars, or even flashlights. The intense fear of German espionage among New Zealanders, combined with spying by neighbors and frequent police visits, created an atmosphere of alienation and helplessness. This was compounded by the refugees’ tormenting concern for loved ones they had left behind in Europe, with whom it was almost impossible to communicate.

Meanwhile, their nerve-wracking daily lives were often dominated by a forced career shift. This frequently meant working as domestic servants, assistants in wool warehouses, or factory workers. For doctors, the situation was particularly difficult. To practice medicine in New Zealand, they had to complete additional training and pass challenging examinations, all while facing restrictions from the local branch of the British Medical Association. A total of 34 refugee doctors managed to gain a foothold in their profession by 1945, including Dr. Georg Lemchen from Berlin, who had begun practicing medicine in 1937 at his sponsor’s group medical practice. After the war, Lemchen took in two of the five Kindertransport children who had made their way to New Zealand, and looked after them.

After modest beginnings, refugees with business backgrounds who identified a gap in the market were sometimes able to establish companies. For example, Viennese chemical technician Arthur Hirschbein (1909–1982) drew on his knowledge of the oil industry to found a company producing chemical industrial goods, which supplied customers such as the New Zealand Railways Department. Like many other German-speaking Jews, Hirschbein anglicized his name—in his case, to Arthur Hilton.

By 1945, Jewish refugees had founded around 123 businesses. Some of these developed into strategically important wartime industries – in fact, seven of these sectors had not existed in New Zealand before.

Although traditional gender roles were far more rigid in New Zealand than in Europe, circumstances forced many women to provide for their families, as in other immigrant societies. The actress Maria Dronke, for example, showed considerable initiative and resourcefulness in converting her small living room on Hay Street in Wellington into a studio for drama and voice production, where she trained New Zealand’s first generation of professional actors during the war years.

Fig. 5: Actress Maria Dronke with participants of the Wallis House Residential Drama School, 1948; private archive, Monica Tempian.

Her husband, Adolf John Rudolf Dronke (1897–1982), who had served until 1928 as personal assistant to Chancellor Wilhelm Marx (1863–1946) at the German Ministry of Justice, was forced to make ends meet as a factory worker.

Many refugee memoirs described New Zealand as both ‘safe’ and ‘boring’. In addition, their new host country was predominantly Anglophone and British. The many small details of everyday life in the Dominion required interpretation, acclimation, and adaptation. For German-speaking immigrants, being classified as ‘enemy aliens’ and having their professional qualifications disregarded were central to their sense of foreignness and otherness. Alienation and isolation shaped the lives of many refugees. In this context, maintaining the German language and culture became an important source of comfort and strength.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, conducting public gatherings in German was no longer permitted by the authorities. The only permanent institution with its own premises that offered refugees a space for social exchange during the war was the Czech Club in Wellington – because refugees from annexed countries were classified as ‘friendly aliens’ and therefore allowed to establish their own coffeehouse, where both Czech and German were spoken. Otherwise, all cultural activities by these groups were confined to private households. In Wellington, the aforementioned Dronkes hosted a literary salon; the Berlin-born musicians Erika Schorss (1908–2009) and Marie Vanderwart-Blaschke (1911–2006) performed in various families’ front yards and gardens.

In Auckland, a small group of refugees regarded the local poet Karl Wolfskehl as a vibrant representative of European culture. In Dunedin, many doctors undergoing retraining at the Otago Medical School gathered in the apartment of Walter Griesbach (1888–1968), a former professor of pharmacology from Hamburg. Meanwhile, many refugee families found an important space for connection at the gatherings hosted by Austrian scholar Caesar Steinhof (1909–1954) in his Maori Hill Bungalow. These private literary and musical salons satisfied refugees’ cravings for familiar culture and slowly cultivated meaningful spaces for exchange with like-minded New Zealanders. Given the geographical isolation of the small island nation, the salons served as crucial meeting places.

In the 1940s, New Zealand had no professional theater, no symphony orchestra, and no regular chamber music concerts. There were no training programs for actors or musicians according to European standards, and there was a shortage of cafés and restaurants. After the war ended in 1945, German-speaking refugees increasingly played an important role in shaping public cultural life. They came together around shared cultural interests through newly founded clubs and associations, and launched new committees and projects. At the initiative of Maria Dronke, the New Zealand Drama Council, the country’s first amateur theatrical association, was established in 1945. In 1946, Adolf John Rudolf Dronke, an accomplished amateur cellist, and violinist Erika Schorss were founding members of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. In the same year, Fred Turnovsky (1916–1994), a businessman from Prague, founded Wellington’s first chamber music society. The introduction of a subscription model inspired by that of Prague’s Deutscher Kammermusikverein (German Chamber Music Society) ensured continuity for the institution in New Zealand, which had some 600 members the year of its founding. Among its first guest performers were the Jewish musicians Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999), Lili Kraus (1905–1986), and Isaac Stern (1920–2001).

The emergence of a café culture, fostered by refugee entrepreneurs such as Hamburg-born Harry Seresin (1919–1994), greatly facilitated the growth of artistic networks. Finally, many German-speaking Jews formed the audience for the cultural sector that emerged in postwar New Zealand, and helped secure its success through their connections to international artists.

New opportunities also opened for refugees in other fields during the postwar years. In 1948, the first Jewish library in Wellington was founded, quickly becoming a major cultural center and home to many collected editions of German literary classics. Around the same time, several German-speaking refugees were hired for academic positions at New Zealand universities, including the historian Peter Munz (1921–2006), who had been born in Chemnitz.

According to the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act (1914), foreigners who had resided for five years in a Dominion of the British Empire, such as New Zealand, could apply for citizenship. However, in October 1940, the Department of Internal Affairs in Wellington suspended the naturalization of refugees from Nazi Germany for the duration of the war. In view of the upcoming 1946 elections, the Labour government ultimately decided to establish a legal basis for integrating refugees into New Zealand society. Given the chance, most of them chose to remain and become citizens.

These South Pacific islands, once so far from home, had become the country where they wished to remain. As was common in New Zealand, many had built their own houses; their children had been born and educated there. German-speaking Jews had created their own solidarity networks and actively contributed to New Zealand’s cultural and economic development. For those who returned to Europe for a visit, their first encounter with their former homelands often reinforced the sense that their lives were now firmly rooted in New Zealand. Very few considered returning permanently after the war – among them Ernst Plischke and Karl Popper, who perceived the intense pressure to conform to colonial attitudes and behavior as a trying ordeal.

The first generation of refugees viewed German language and culture as part of their heritage, which they were able to take with them to a new continent. This enduring attachment to their culture of origin also left an indelible mark on their children raised in the diaspora. Many of them described the strange sensation of visiting Germany or Austria, speaking fluent German, not being perceived as foreigners – and yet feeling foreign all the same. Sir Thomas Eichelbaum (1931–2018), Chief Justice of New Zealand from 1989 to 1999, who had been born in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) and fled to New Zealand at the age of seven, attributed his exceptional professional achievements to cultural values such as punctuality, precision, and industriousness, which he associated with his German identity.

Similarly, most former child refugees described their sense of Jewishness in terms of a secular worldview based on ethics and morality. This outlook had already been notable in their parents’ generation and was significantly shaped by early experiences of antisemitism. It also inspired many of them to establish commemorative spaces and to raise public awareness in New Zealand of the history of German-speaking Jewry. In 2007, when the Holocaust Centre of New Zealand (HCNZ) opened in Wellington, the Vienna-born founding director Inge Woolf, née Ponger (1934–2021), explained that the center’s primary goals were Holocaust education in New Zealand schools and public remembrance. The work of the HCNZ is complemented by the activities of the Auckland-based Holocaust and Antisemitism Foundation Aotearoa New Zealand. Since 2012, this foundation has focused on collecting and archiving survivors’ testimonies and curating exhibitions. One of its longtime chairs is Robert Narev, born 1935 in Eschwege and one of the few survivors of the Theresienstadt ghetto, who is dedicated to preserving the memory and legacy of German-speaking Jewry.

By contrast, the second and third generations tend to see themselves as New Zealanders, identifying strongly as Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent) – a term that resists clear ethnic or cultural categorization and instead reflects the many layers of New Zealand’s settlement history. The key experiences of displacement and re-rooting, the emotions preserved in memory, and the meanings attached to these layers of identity play a central role in the discussions of second- and third-generation groups in Wellington and Auckland. The Wellington group, founded in 2018 by business communication lecturer Irene Buxton, née Frohlich (born in 1944), now has 70 members. According to Buxton, the group’s meetings – especially for the descendants of refugees from Chemnitz – have been instrumental in helping members come to terms with what it meant to grow up as the child of refugee parents from the other end of the world.

Today, there is no longer an active German-speaking diasporic culture in New Zealand. However, in recent years, programs of official visits organized by various German cities seem to have played a positive role in sparking interest in the little-researched personal archives of departed German-speaking Jews. In several cases, they have inspired descendants to engage artistically with their family histories. Since Ann Beaglehole’s pioneering work in 1988, research on the refugee generation has gained new momentum in recent years, particularly through conferences and publications by scholars at Victoria University of Wellington and the University of Auckland. In 2024, the first systematic research and data collection began on the history of the German-speaking Jewish community during the colonial period – a history that had previously been limited to a handful of brief references to the contribution of individual settlers.

Conversation with historian Ann Beaglehole about New Zealand’s refugee history, Jewish Lives New Zealand: https://www.jewishlives.nz/podcast/episode-3

Conversation with Claire Bruell about her experiences as the child of Holocaust survivors who found refuge in New Zealand, Jewish Lives New Zealand: https://www.jewishlives.nz/podcast/episode-5

Television New Zealand’s Neighbourhood Series 3 with survivors of the Shoah and the Holocaust Centre of New Zealand, episode 31: Karori. Production company Satellite Media Ltd, 2015: https://youtu.be/7zifCNjdbRQ

The Third Richard, documentary film by Danny Mulheron and Sara Stretton about the German-Jewish composer Richard Fuchs (1887–1947), who fled to New Zealand, 2019: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HjhqfiWjr5k

Opening of the Anne Frank Memorial in Wellington, June 13, 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMnxOw_4epA

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Dr. Monica Tempian (https://people.wgtn.ac.nz/monica.tempian) is a Senior Lecturer in German language and literature at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. Her research focuses on the interrelated areas of Diaspora and Exile Studies, Memory Studies, Multicultural Literatures, and German-Hebrew Studies. Her most recent publications include (with Jan Kühne), Manfred Winkler, “Noch hör ich deine Schritte”. Deutsch- und hebräischsprachige Gedichte (100th anniversary edition of Manfred Winkler’s bilingual, German and Hebrew poetry), Frankfurt: Edition Faust, 2022; (with Hans-Jürgen Schrader), Manfred Winkler, Haschen nach Wind: Die Gedichte, Wien/Würzburg: Arco Verlag, 2017; Minnie Maria Korten. Ein Schauspielerleben rund um die Welt, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2015 (in English: Maria Dronke. Glimpses of an Acting Life, Wellington: Playmarket, 2021; (with Simone Gigliotti), The Young Victims of the Nazi Regime: Migration, the Holocaust, and Postwar Displacement, London/New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

Monica Tempian, A Refuge in the Furthest Promised Land: German-Speaking Jews in New Zealand, in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, May 08, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-8> [February 19, 2026].