Born on December 5, 1897 in Berlin,

Germany

Died on February 21, 1982 in Jerusalem, Israel

Occupation: Professor, historian, philosopher

Migration: Mandatory Palestine (today Israel), 1923

“I turned away from a German feeling with complete consciousness not in 1917, but rather no later than 1913.” Gershom Scholem to Reinhold Scholem, 29.05.1972; National Library of Israel, Archives Department, Arc. 4*1599, series 01, file 3031. The famous German-born Israeli scholar Gershom Scholem wrote these words in a letter to his brother Reinhold Scholem (1891–1985) in 1972, as they evaluated the situation of German Jewry in their youth and Scholem prepared to write his memoir Von Berlin nach Jerusalem (From Berlin to Jerusalem, 1977). Reinhold Scholem maintained that German Jews had had a place in German society before the Nazi era. By contrast, his younger brother insisted that the German Jews had never been truly accepted in German society and claimed that he had rejected an identity as a German (or Jewish-German) in favor of an exclusively Jewish identity even before the First World War, which led to an increase in popular antisemitism.

From an early age, Gershom Scholem intended to make Aliyah, doing so in 1923. However, despite presenting his identity as solely Jewish – and later Israeli – rather than German or German-Jewish, Scholem maintained both a lifelong attachment to German culture and a significant connection to the German-speaking scholarly community.

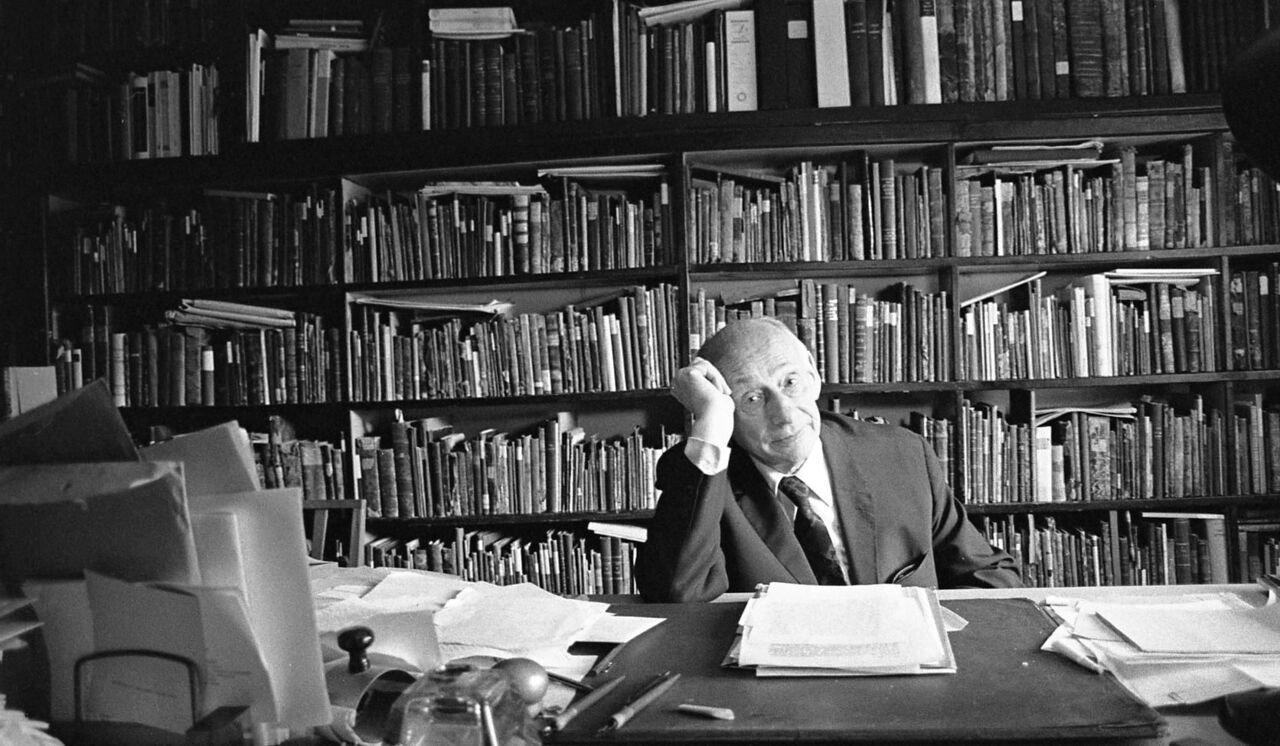

Fig. 1: Gershom Scholem in his library, Jerusalem, 1974; Aliza Auerbach Archive, ARC. 4* 2025 01 18A 0013, National Library of Israel.

Gershom Scholem, born Gerhard, was the youngest son of Arthur Scholem (1863–1925) and Betty Scholem née Hirsch (1866–1946). He was raised in the Neukölln am Wasser and Luisenstadt neighborhoods of central Berlin, where his parents owned a print shop. His family was not religious and rarely attended services. Scholem had a bar mitzvah at Berlin’s liberal Lindenstraße synagogue days before his fourteenth birthday. Though his family gathered with aunts, uncles, and cousins for Shabbat and holiday meals, young Scholem felt that his family neither respected nor valued Jewish traditions, and in December, a Christmas tree adorned their parlor. Repelled by his parents’ relationship to Judaism, Scholem sought more meaning in Judaism. As a boy, he studied with Rabbi Isaac Bleichrode (1867–1954) and briefly practiced Orthodox Judaism before realizing his Jewish identity through Judaic scholarship and use of the Hebrew language.

Fig. 2: Gershom Scholem (on the right) with family members in Schierke, Harz, 1913; Gershom Gerhard Scholem Archive, ARC. 4* 1599 10 08, National Library of Israel.

Scholem was an active Zionist, though he espoused cultural Zionism along the lines of the journalist and Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am (1856–1927) and opposed traditional, Herzlian political Zionism. While a student in Jena, Heidelberg, and Munich, Scholem was involved in study groups that focused on Jewish texts in Hebrew. He completed his doctorate in Semitic studies at the University of Munich in 1922 with a dissertation on a Jewish mystical text, the Book of Illumination (Sefer ha-Bahir), which was published the following year. Around that time, he also taught classes on the Kabbalah at the Free House of Jewish Study (Freies Jüdisches Lehrhaus), founded in Frankfurt by the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929).

Through friends studying in Heidelberg, Scholem met Elsa (called ‘Escha’) Burchhardt (1896–1978), the daughter of an Orthodox Jewish physician from Hamburg. Having similar interests and similar opinions about Judaism and Zionism, a friendship developed, which turned into a romantic relationship. They made plans to make Aliyah and marry. In September 1923, in the final months of the so-called Third Aliyah – the third major wave of modern Jewish immigration to Palestine – Scholem traveled to Mandatory Palestine together with the German-born scholar Shlomo Dov Goitein (1900–1985), who was also making Aliyah. Scholem and Escha Burchhardt married on his twenty-sixth birthday, December 5, 1923.

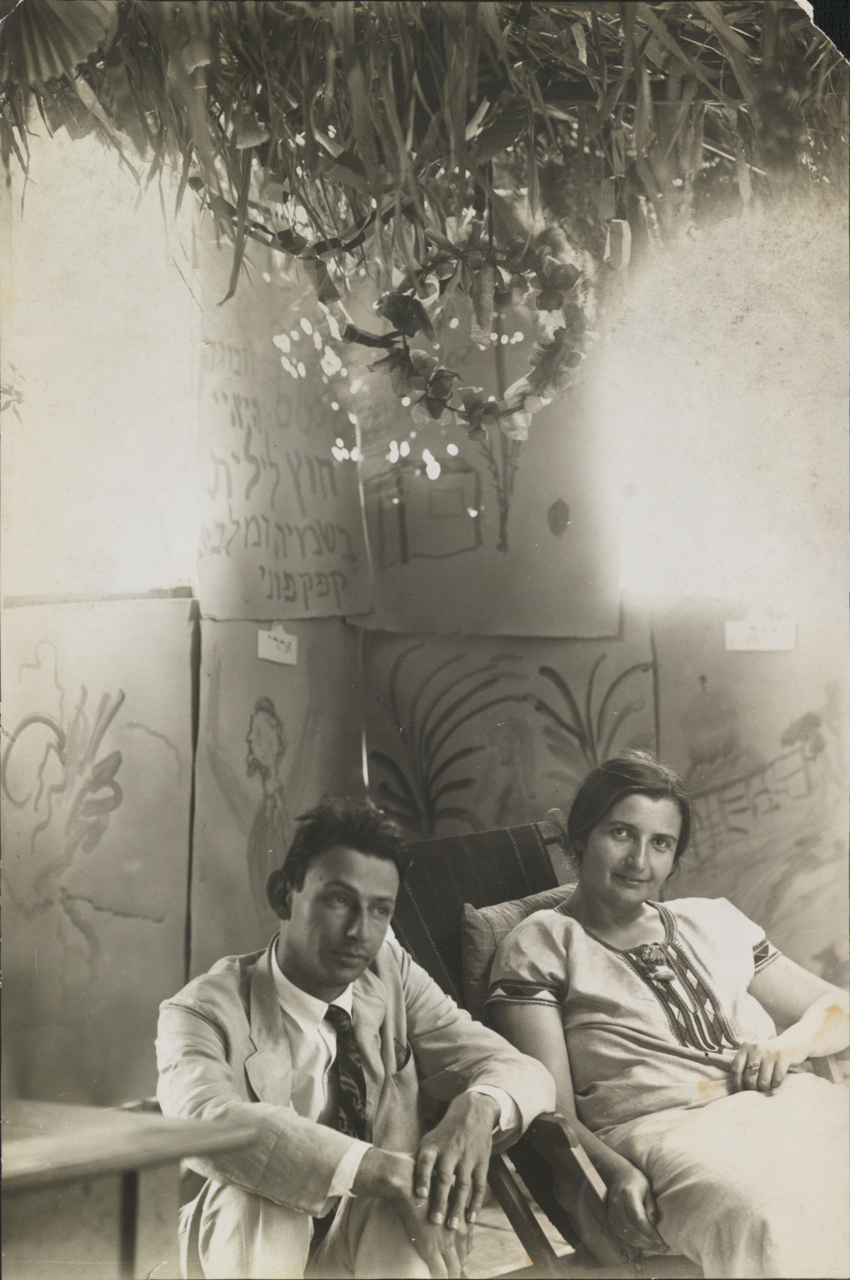

Fig. 3: Gershom and Escha Scholem in a Sukkah, 1926; Gershom Gerhard Scholem Archive, ARC. 4* 1599 10 23, National Library of Israel.

Soon after arriving in Palestine, Scholem took a position as a Hebrew-language bibliographer at the Jewish National Library in Jerusalem. After the establishment of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925, he was offered a position as a lecturer and eventually was promoted to the rank of Professor and dean of the Faculty of Humanities. He helped install European and especially German standards of academic rigor and scholarship at the young university.

By the 1960s, Scholem was one of the most important scholars in Israel, with an international reputation and many honorary doctorates and prizes, including the Israel Prize. In 1968, he became president of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, established seven years earlier as a national focal point for Israeli scholarship in the natural sciences and the humanities.

In the years after making Aliyah, Gershom Scholem had a social circle that was overwhelmingly comprised of intellectuals from German-speaking Central Europe. Among his closest friends was Shmuel Hugo Bergmann (1883–1975). Originally from Prague, Bergmann was director of the National Library and later a professor at the Hebrew University. In 1932, the architect Lotte Cohn (1893–1983), originally from Berlin, designed a duplex for the Bergmanns and the Scholems in Jerusalem’s Rehavia neighborhood, which was often described as a German-Jewish neighborhood that offered modern homes, parks, and cafés. It was especially popular with the secular or semi-secular intelligentsia and immigrants from Central Europe.

A few years later, the Bergmanns and the Scholems both divorced. Hugo Bergmann then married Escha Scholem, and Gershom Scholem married Fania Freud (1909–1999), who had immigrated from Galicia and studied under Scholem’s direction at the Hebrew University. Gershom Scholem moved out of the duplex and into an apartment in a house also designed by Lotte Cohn, just three minutes’ walk away.

Scholem was also politically active in Jerusalem, most famously as a member of the Brit Shalom (covenant of peace) association, a group of Jews – mainly German-speaking intellectuals from Central Europe – who promoted Arab-Jewish reconciliation and the establishment of a binational state in Palestine. Even after the violence of riots in Hebron and Jerusalem in 1929, Scholem harbored hopes for binationalism. Only later, and reluctantly, did he come to support the partition of Mandatory Palestine and the creation of a small Jewish-majority state.

Although Scholem was a master of the Hebrew language and published scholarly essays and books in Hebrew, he maintained his connection to the German language. His famous book Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941) was first composed in German and then translated into English. The use of German allowed Scholem to remain connected to the international scholarly community. Even in his private life, he continued to speak German and to correspond with family and friends in German. Indeed, many of his close friends continued to call him ‘Gerhard’, not ‘Gershom’. Scholem maintained an express preference for German products while living in Mandatory Palestine. His correspondence with his mother was full of requests for German-made clothes, foodstuffs, including sausage or marzipan, and household products. Scholem was also known for his formal style of dress, which was more typical of Germany than of the relaxed atmosphere of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine.

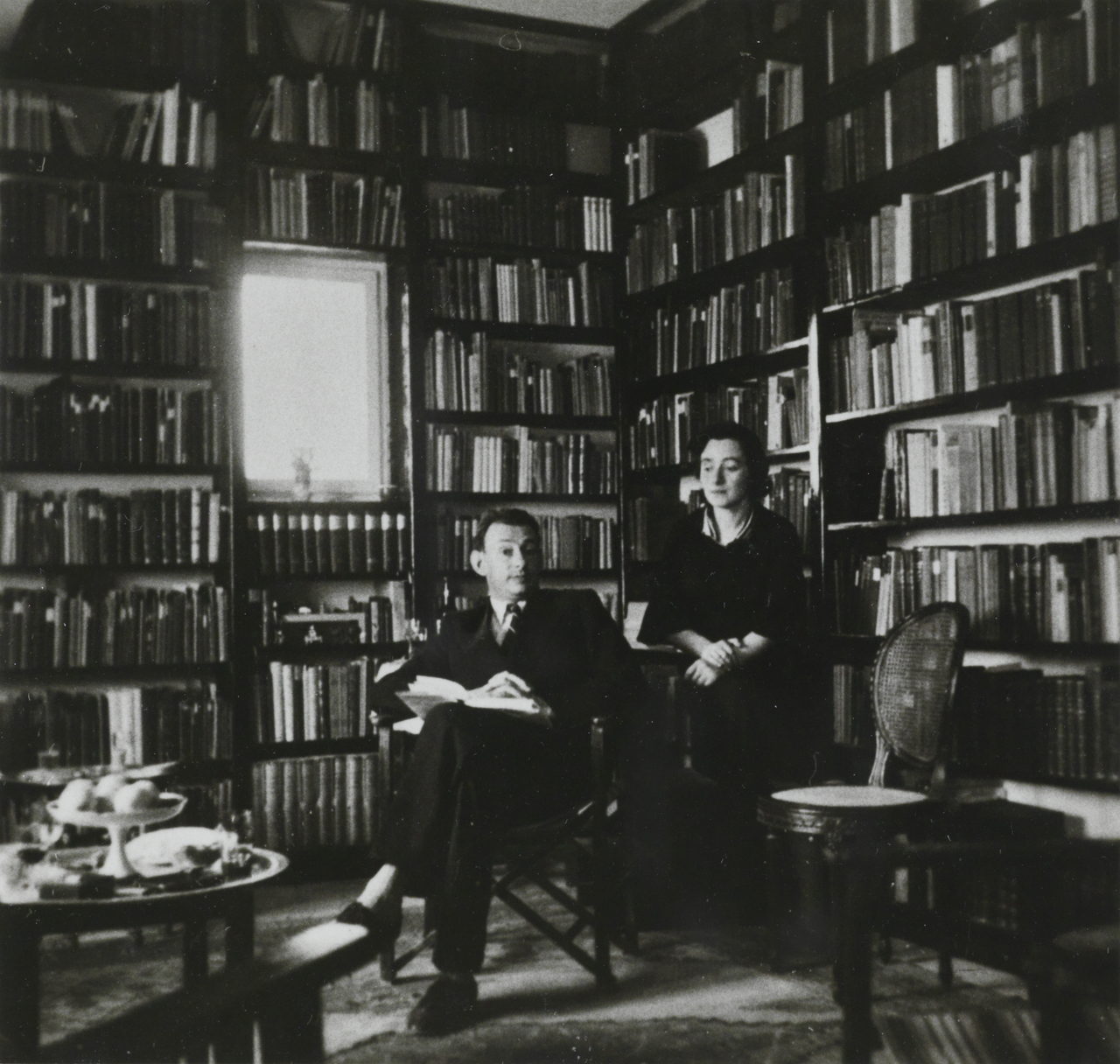

Fig. 4: Gershom and Fania Scholem at their home in Rehavia, Jerusalem, around 1939; Gershom Gerhard Scholem Archive, ARC. 4* 1599 10 45, National Library of Israel.

In 1933, the Nazis came to power, and the political, economic, and social situation of the Jews of Germany rapidly deteriorated. Tens of thousands of German Jews, and later Austrian and Czech Jews, who had not been Zionists, moved to Palestine in the so-called Fifth Aliyah, the wave of immigration between 1929 and 1939. While many of the refugees would have preferred sanctuary in the United States, Great Britain, or another European country, the urgency of their situation and difficulty of gaining admittance elsewhere often tipped the balance in favor of Palestine.

Scholem, who had immigrated to Palestine in 1923 out of Zionist conviction, especially cultural Zionist conviction, showed little sympathy for the recent arrivals. On 26 April 1933, he wrote to his mother, Betty Scholem, who was still in Berlin: “On one of the last ships, there arrived a district court judge, who explained to the relief committee that he is ready to do any kind of work, demands only a minimum wage (nonetheless approximately RM 200), and would even, if it were necessary, give up his title. For this gentleman, such a proclamation is surely an expression of the most extreme sacrifice; for a local Jew, it is an incomprehensible curiosity.” Gershom Scholem to Betty Scholem, 26.04.1933, in: Betty Scholem/Gershom Scholem, Mutter und Sohn im Briefwechsel, 1917–1946, ed. by Itta Shedletzky, München: C. H. Beck, 1989, 297.

The German Jewish migrants of the Fifth Aliyah had great difficulties with life in Mandatory Palestine, including the climate, social conditions, and economic situation, but they also transformed the society of the Yishuv. Their presence and their investment capital in the cities led to the establishment of shops, cafés, and places of entertainment that catered to a more sophisticated clientele than had previously been the case. Scholem disapproved of this trend. At the end of 1934, he wrote to his mother that he could not convince newly arrived German Jews that Palestine did not need luxury shops. He explained that “the early settlers had immigrated to a stranger, wilder region and without any connection, to say nothing of jobs.” Gershom Scholem to Betty Scholem, 26.12.1934, in: ibid, 377. And despite his own use of German, he felt discomfited by the immigrants’ widespread and public use of the language. As he wrote to his friend, the German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940): “One hears German spoken on the streets to such an extent here, and even more conspicuously in Tel Aviv […] that it makes people like me feel even more like withdrawing into Hebrew.” Gershom Scholem to Walter Benjamin, 15.06.1933, in: Walter Benjamin/Gershom Scholem, The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem, 1932–1940, edited by Gershom Scholem, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992, 56.

Gershom Scholem was one of four brothers. His oldest two brothers, Reinhold and Erich Scholem (1895–1965), escaped to Australia in 1938. However, his brother Werner Scholem (1895–1940), to whom Scholem was closest, was arrested in 1933 and murdered in Buchenwald concentration camp in 1940. Their mother was able to flee Berlin and join her oldest sons in Sydney in 1939. On his father’s side of the family, Scholem had cousins and an aunt and uncle who fled to Palestine. His mother’s brother found refuge in Brazil, but his mother’s sister was unable to emigrate and died in the Theresienstadt Ghetto in 1943. Scholem’s best friend, the aforementioned Walter Benjamin, committed suicide in September 1940, fearing that he would be turned over to the Gestapo by the French police. By 1945, European Jewish civilization had been destroyed. At the war’s end, Scholem was deeply depressed and pessimistic.

Fig. 5: Erich, Gershom, and Reinhold Scholem in Montreal, 1938 (from left to right). Erich and Reinhold Scholem were on their way to Australia via Canada, while Gershom Scholem was spending time in the United States as a visitor scholar; Gershom Gerhard Scholem Archive, ARC. 4* 1599 10 47, National Library of Israel.

In 1946, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem sent Scholem to Europe to claim heirless Jewish books and have them sent to Jerusalem before American or other Diaspora Jewish institutions could take them. Seeing the remnant of a once flourishing civilization further darkened his mood. Nonetheless, beginning in the 1950s, Scholem began a process of scholarly exchange with German-speaking European scholars and later worked for German-Jewish rapprochement. He frequently visited Europe, where he spoke at German universities, was interviewed for German newspapers, and even appeared on German radio. Scholem’s writings, many of them originally composed in German, gained a significant readership in the Federal Republic of Germany and Switzerland.

In the winter of 1981/1982, Scholem took a position as a member of the first class of fellows at the newly founded Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin (Berlin Institute for Advanced Study). However, he fell ill during that time and was unable to return to West Berlin after a visit back to Jerusalem.

Gershom Scholem died in February 1982. His tombstone in Jerusalem’s Sanhedria Cemetery expressly notes that he was “A man of the Third Aliyah”, emphasizing that Scholem arrived as a Zionist and not as a Yekke, a Jew fleeing Nazi Germany with the Fifth Aliyah.

The Gershom Scholem Collection relating to the field of Kabbalah and based on the extensive personal library of Scholem at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem: https://www.nli.org.il/en/at-your-service/who-we-are/collections/scholem-collection

Tour of the Gershom Scholem Collection with Zvi Leshem at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, August 17, 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SoKjm6_OejU

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Prof. Dr. Jay Howard Geller is the Samuel Rosenthal Professor of Judaic Studies in the Department of History at Case Western Reserve University. His research explores the history of Jews in modern Germany, with particular focus on Jewish politics, identity, and urban life. He has written extensively on German-Jewish history, including Jews in Post-Holocaust Germany, 1945–1953 (Cambridge University Press, 2005) and The Scholems: A Story of the German-Jewish Bourgeoisie from Emancipation to Destruction (Cornell University Press, 2019; German edition: Die Scholems, Suhrkamp, 2020). Geller has co-edited several volumes, including Three-Way Street: Jews, Germans, and the Transnational (University of Michigan Press, 2016, with Leslie Morris) and Rebuilding Jewish Life in Germany (Rutgers University Press, 2020, with Michael Meng).

Jay Howard Geller, Gershom Scholem (1897–1982), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, September 15, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-36> [February 03, 2026].