Jews have never constituted more than a vanishingly small minority in Japan – of which German-speakers form an even smaller fraction. Of the country’s nearly 125 million inhabitants today, only around 2,000 are Jewish, most of them foreign nationals residing in the country temporarily as diplomats, business executives, or language teachers. Nevertheless, Japan had a historically significant relationship with groups of Jewish refugees, particularly during the years of Japan’s imperial expansion between 1931 and 1945.

First, roughly 10,000 Jewish refugees from Russia who were living in northeastern China, mainly in the city of Harbin, came under Japanese rule during this period. Later, approximately 4,000 Jewish emigrants – many from Germany and Austria – found refuge in Mainland Japan. Some had arrived even before the Nazi rise to power, seeking to pursue artistic or scholarly careers there, for example. In addition, about 18,000 Jewish refugees, primarily from Germany, Austria, and Poland, sought shelter from the Nazi regime in the port city of Shanghai. Beginning in 1937, large areas of Shanghai came under Japanese control. From late 1941 until the end of the war, Japan held the entire city. Japanese government and military authorities’ treatment of these refugees was deeply shaped by both antisemitic and philosemitic ideas circulating globally at the time. These notions have continued, in various ways, to shape Japanese perceptions of Jews to this day.

For two hundred years, Japan maintained a policy of isolationism, during which there were no known traces of Jewish life in the country. A few years after 1853, when the country was forced to open to the West under US pressure, Jewish merchants arrived from Europe and the United States, settling in port cities such as Yokohama, Nagasaki, and Kobe. These foreigners enjoyed certain privileges – for instance, they and other residents from Western countries were not under the jurisdiction of the Japanese legal system. To the Japanese, these Westerners appeared as a privileged group, regarded as a seemingly homogeneous community of predominantly ‘white’ Westerners differing only by nationality.

With the accession of Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) in 1868, Japan entered a period of intense reform and modernization. More merchants and businesspeople arrived, among them the first German-speaking Jews. Among these were Rubin Haskell Goldenberg (1839–1898), a German citizen born in Romania, and Sigmund David Lessner (1859–1920), an Austrian citizen from Bukovina. Both lived in Nagasaki and achieved notable success – Goldenberg in the hospitality trade, and Lessner as a businessman.

At that time, Nagasaki was also home to around one hundred Jewish families from the Russian Empire who had fled pogroms in their places of origin. Gradually, a Jewish community emerged there, supported above all by the construction of the Beth Israel Synagogue, which opened in 1896 as one of Japan’s first synagogues. Goldenberg and Lessner were among the principal benefactors supporting its construction.

Roughly fifty Jewish families – mainly from the United States, England, and Poland – lived in Yokohama, where Japan’s first synagogue was opened in 1895. After the First World War, the center of Western immigrant life in Japan – and by extension, Jewish life – gradually shifted to Yokohama and Kobe.

Fig. 1 and 2: Nora Tavor, née Heller, as a young girl in Yokohama, 1909 (left), and as a toddler with her Japanese nanny (right). Tavor was born in 1906 into a Jewish family from Prague that had settled in Yokohama’s growing Jewish community. Her father ran an insurance agency, and her mother was a Classical singer. Moshe and Nora Tavor Collection, AR 6148, F 80522 and F 50824, Leo Baeck Institute.

Many foreigners also lived in the capital of Tokyo, among them German-Jewish merchants such as Michael Martin Bair (1841–1904), who had settled in Japan in 1869. Thanks to his strong ties with the Japanese government, Bair was even temporarily appointed the German consul. In 1873, he was also among the founding members of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens (German East Asiatic Society, known by the abbreviation, OAG) in Tokyo. Modeled on the British Asiatic Society of Japan, the OAG began as a scholarly society but soon became the most important social club for Germans in Japan. Its members often included German merchants, scholars, and experts (oyatoi gaikokujin), who had been recruited by the Japanese government to support the country’s modernizing reforms.

At that time, Japan regarded Germany as a role model to emulate in many respects, admiring the country’s military, legal, and constitutional systems as well as its accomplishments in areas such as medicine, the humanities, and music. By the 1880s, there was a circle of about two hundred “Meiji Germans,” most of whom lived in Tokyo or Yokohama, viewing themselves as an exclusive (and exclusively male) elite shaping German–Japanese relations. Around ten percent of this group were Jewish.

When an 1886 article in Leipzig’s Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums (General Newspaper of Judaism) claimed “the restrictions and discrimination against Jews” Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums, 14 September 1886, no. 38, 603. common in many European countries did not exist in Japan, it overlooked the imported antisemitism that prevailed among many Meiji Germans and made life difficult for their Jewish peers.

One target of these attitudes was Albert Mosse (1846–1925), a German-Jewish legal scholar from the prominent Mosse family of Berlin. From 1886 to 1890, Mosse served as legal adviser to the Japanese cabinet and became one of the most influential foreign experts in Meiji Japan. In letters from Japan, Mosse complained about the other local Germans, including his legal colleagues, who – as he wrote in 1887 – were “inwardly consumed by antisemitism.” Albert Mosse, letter dated 26 June 1887, quoted in Rolf-Harald Wippich, “Judenfeindschaft unter den Deutschen in Meiji-Japan (1868–1912),” in: Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung 30 (2021): 79.

One Jewish contemporary was the historian Ludwig Rieß (1861–1928) from Berlin, who served as a professor of history at the Imperial University of Tokyo from 1887 to 1902, where he introduced Western methods of historiography, such as the ideal of adopting a neutral perspective in historical writing.

Despite the prejudice they faced, both Mosse and Rieß remained active within the larger German community. For example, both were members of the OAG. Rieß even served on its board and later became an honorary member. With so few German-speaking Jews in Japan, this specific demographic did not have any of its own organizations or associations, and they were thus somewhat dependent on these broader-based societies.

Fig. 3: Order of the Rising Sun (kyokujitsushō) awarded to Albert Mosse, c. 1890. Mosse received this decoration – awarded since 1875 in recognition of exceptional service to Japanese culture and society – for his achievements as the most influential foreign legal adviser to the Japanese government. Mosse Family Collection, AR 25184, 61.79a, Leo Baeck Institute.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 marked the first time Japanese society developed specific conceptions about Jews or Jewishness. Many Jews in the global Diaspora supported Japan in this conflict because Tsar Nicholas II (1868–1918), who led the opposing side, was notorious for his antisemitic policies, which had led to numerous pogroms under his reign. Many Jews, therefore, hoped that a Russian defeat would improve circumstances for the empire’s Jewish population. The American banker Jacob Henry Schiff (1847–1920), born into a Frankfurt Jewish family, helped finance Japan’s war effort by arranging the sale of Japanese government bonds, ensuring that Japan had sufficient funds to win the war. This brought Schiff fame and honor in Japan, though Japanese press reports about him often reflected the stereotype of Jews as inherently wealthy and powerful.

Yet these early stereotypes were soon replaced by imported, explicitly antisemitic ideas. After Japan’s victory in the First World War, Japanese troops were sent to Siberia in 1918 to support the Russian White Army against the Bolsheviks. In Siberia, Japanese soldiers encountered antisemitic propaganda, including the Protocols of the Elders of Zion – a forgery first published in 1903, probably written by Russian antisemites and fabricating a Jewish conspiracy for world domination.

In 1931, the Japanese army occupied Manchuria in northeastern China and, a year later, established the puppet state of Manchukuo (State of Manchuria) under its control. This put more than 10,000 Russian Jews – some of whom had fled to China during the upheavals of the Russian Revolution, and many now living in the Manchurian city of Harbin – under Japanese rule. Some Japanese military officials and industrialists began to see these Jewish refugees as potentially useful to Japan’s national interests. There were even proposals to encourage further Jewish settlement in Manchuria, in the hope that Jewish communities in the United States might then be persuaded to invest capital there.

These schemes, however, were not universally accepted within the Japanese military. Japan’s growing alliance with Nazi Germany – formalized in 1936 with the so-called Anti-Comintern Pact, primarily established as a counterweight to the Soviet Union – emboldened radical antisemites in Japan. One of these was Lieutenant General (chūjō) Shiōden Nobutaka Following Japanese practice, Japanese names in this article list the family name before the given name, the opposite sequence from English names. Diacritics marking long vowels in the names of well-known cities have been omitted. (1879–1962), who promoted a variety of antisemitic campaigns in the media and politics alongside other ultranationalists.

Thus, two opposing camps emerged within Japan: on one side, those who sought to ‘make use’ of Jews for the nation’s benefit by encouraging limited settlement under Japanese control; and on the other, those who – like their German counterparts – wanted to exclude Jews from society altogether and keep them away from Japanese soil if possible.

The annexation of Austria by the German Reich in 1938 and the pogroms of that November led to a sharp rise in Jewish emigration, some of which reached Japanese shores. The port city of Kobe, for instance, served as an important transit point for refugees seeking to travel onward to the United States or other destinations. Their escape routes often led through territories under Japanese control or within the empire’s sphere of influence, including Shanghai and Manchukuo.

Most European refugees reached East Asia by ship from Italian ports, a route that remained open until June 1940, when Italy entered the war as Germany’s ally. Thereafter, the only remaining option was the land route via the Trans-Siberian Railway – that is, until the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 made even that passage impossible.

Shanghai had been captured by Japanese forces in 1937, during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The city’s International Settlement (primarily under British and American control) and its French Concession were the only districts not occupied by Imperial Japan. The International Settlement – including the Hongkou district, which was home to both Chinese and Japanese residents – came under nearly total Japanese control from the early 1930s onward. Beginning in 1938, large numbers of Jewish refugees from Europe settled there. In mid-1943, the Japanese authorities created what became known as the Shanghai Ghetto, a roughly 2.5-square-kilometer area to which about 18,000 German and Austrian Jews were forcibly relocated from other parts of the city. Despite the often intolerable living conditions there, most survived the Shoah.

Fig. 4: Barbed-wire barricades and sandbags in Shanghai, c. 1937. Photograph by Suse Schauss titled “Drahtverhaue in den Strassen Shanghais” (Barbed Wire in the Streets of Shanghai). Private collection Sonja Mühlberger.

Faced with this wave of Jewish immigration, the Japanese government adopted a formal immigration policy in December 1938. It was decided at a conference of key ministers known as the Five Ministers’ Conference. The resulting policies for the treatment of Jews represented a compromise between the two opposing camps described earlier. Under the new resolution, Jews residing in Mainland Japan or in territories under Japanese control, as well as those seeking entry, were to be treated like other foreigners. However, in accordance with antisemitic pressures within the administration, their immigration was expressly not to be encouraged.

In practice, this restriction had a limited effect. Jews from Europe – especially Germany and Austria – continued to reach Shanghai, provided they could secure passage there. A few even managed to flee as late as June 1941. By October 1941, however, the Nazi regime had prohibited all Jewish emigration from the German Reich.

In Mainland Japan, there were essentially two groups of German-speaking Jewish émigrés. The first group consisted of those who were passing through – more or less involuntarily – for whom Japan, and especially the port cities of Yokohama and Kobe, served as a temporary waystation en route to other destinations. Many, however, needed to stay there for some time before they could continue their journeys. One such example was the Katzenstein family, who fled Germany in 1940 by way of Moscow and Manchukuo, eventually reaching Kobe. There they lived for a time among other refugees and cooked meals for fellow exiles. A second group comprised German-Jewish scholars and musicians who had come to Japan for professional reasons, often at the invitation of Japanese institutions, before the Nazi Party took power in 1933.

This group included the Leipzig-born physicochemist Louis Hugo C. Frank (1886–1973), who lived in Japan from 1913 to 1949 with his wife, Amy Frank (1884–1979), and their two sons. He taught courses in materials science and electrochemistry – first at the Otaru Higher Commercial School on Hokkaidō, and from 1926 at a technical college in Kōfu, later incorporated into the University of Yamanashi. As was typical among foreigners who lacked fluency in Japanese, Frank lectured in English.

In 1944, the Franks – like other citizens of ‘friendly countries’ – were evacuated to the mountain resort town of Karuizawa, while nationals of ‘enemy countries’ were imprisoned in internment camps. The evacuation was also meant to protect residents from US air raids. Their elder son, Hugo C. Frank (?–1945), was later arrested on unfounded espionage charges and died in prison in June 1945. After the war, the surviving family emigrated to the United States, which had become the preferred destination for most German-Jewish refugees in Japan.

Fig. 5: From left to right: Hugo, Louis, Amy, and Ludy (Ludwig) Frank in front of the Great Buddha (daibutsu) of Kamakura, 1934. Gift of the Frank family. Courtesy of W. Puck Brecher.

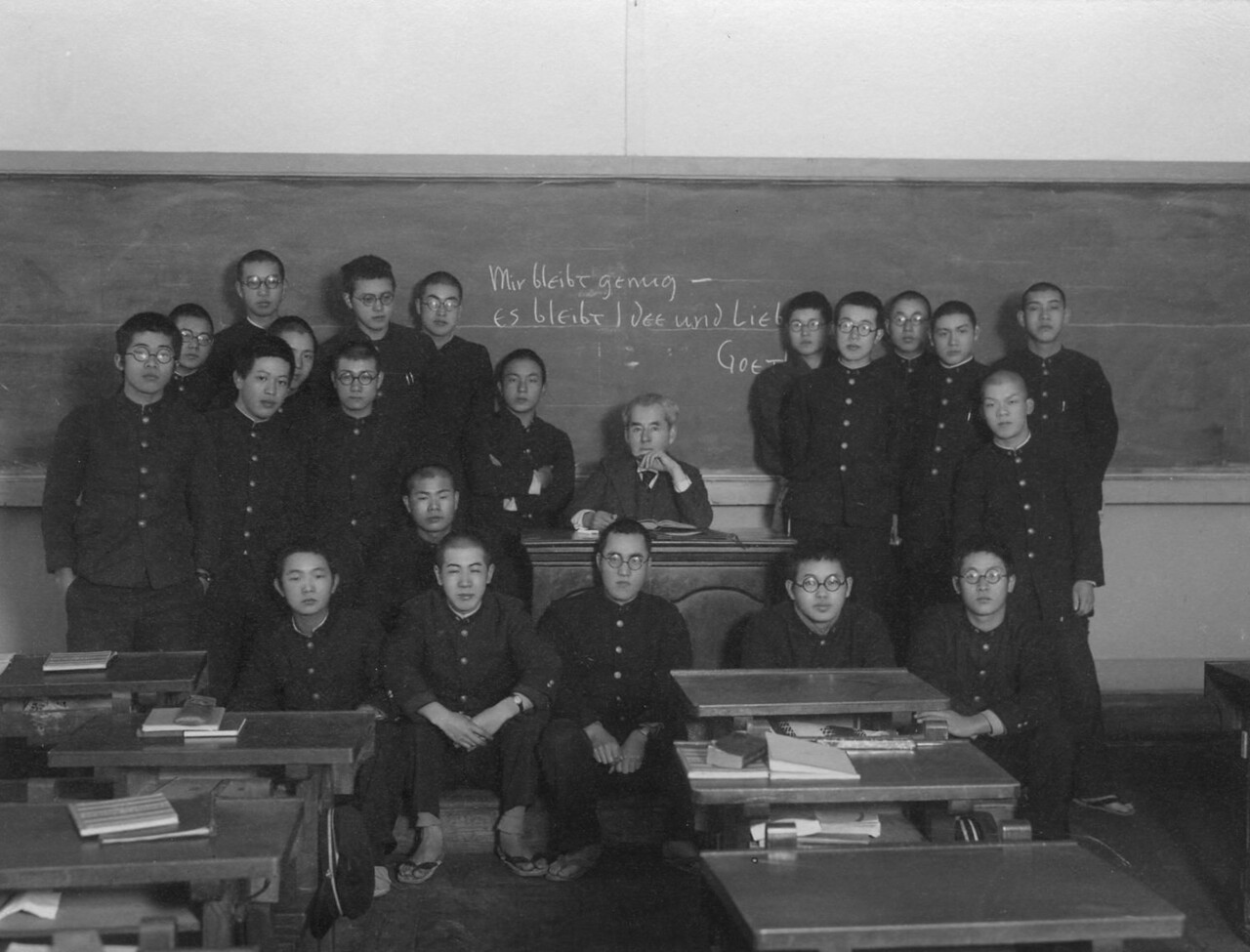

Another scholar was the philosopher, economist, and cultural scientist Kurt Singer (1886–1962). He was appointed to a temporary position at the University of Tokyo in 1931, which he held until 1935. Unwilling to return to Germany as a Jew, he accepted a less prestigious post as a German teacher at a secondary school (Dai ni kōtō gakkō) in Sendai, northern Japan. Many émigrés, especially Jewish ones, experienced similar professional setbacks.

In 1938, Singer was dismissed from his position under pressure from Nazi Party (NSDAP) institutions in Japan, including the Tokyo–Yokohama NSDAP Local Group and the National Socialist Teachers’ League (NSLB). One year later, Singer emigrated to Australia, where he wrote the book Mirror, Sword and Jewel (published posthumously in 1973), reflecting on his experiences and observations in Japan. Although deeply marked by Singer’s cultural pessimism – his rejection of modernity and idealization of elitist leadership – it remains an important Western perspective on Japan. He returned to Europe in 1957 and died in Athens in 1962.

Fig. 6: Kurt Singer with his students in Sendai, 1938. The group photograph was taken on his last day of class. A Goethe quotation on the blackboard translates to “I have enough yet – love remains, and the idea!”; Tohoku University Archives/Tōhoku daigaku shiryōkan shosai.

The philosopher Karl Löwith (1897–1973), a student of Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), likewise escaped Nazi persecution for his Jewish ancestry by emigrating to Japan. He himself was baptized as a Protestant. In 1936, Löwith was appointed to the Tōhoku University in Sendai, where Singer also lived. At the university, he delivered his lectures in German – as was expected of him, given the strong tradition of German philosophy in Japan. Löwith emigrated to the United States in 1941 and returned to Germany in 1952, later becoming a professor of philosophy in Heidelberg. He had been one of the most outspoken critics of Nazism among German academics in Japan.

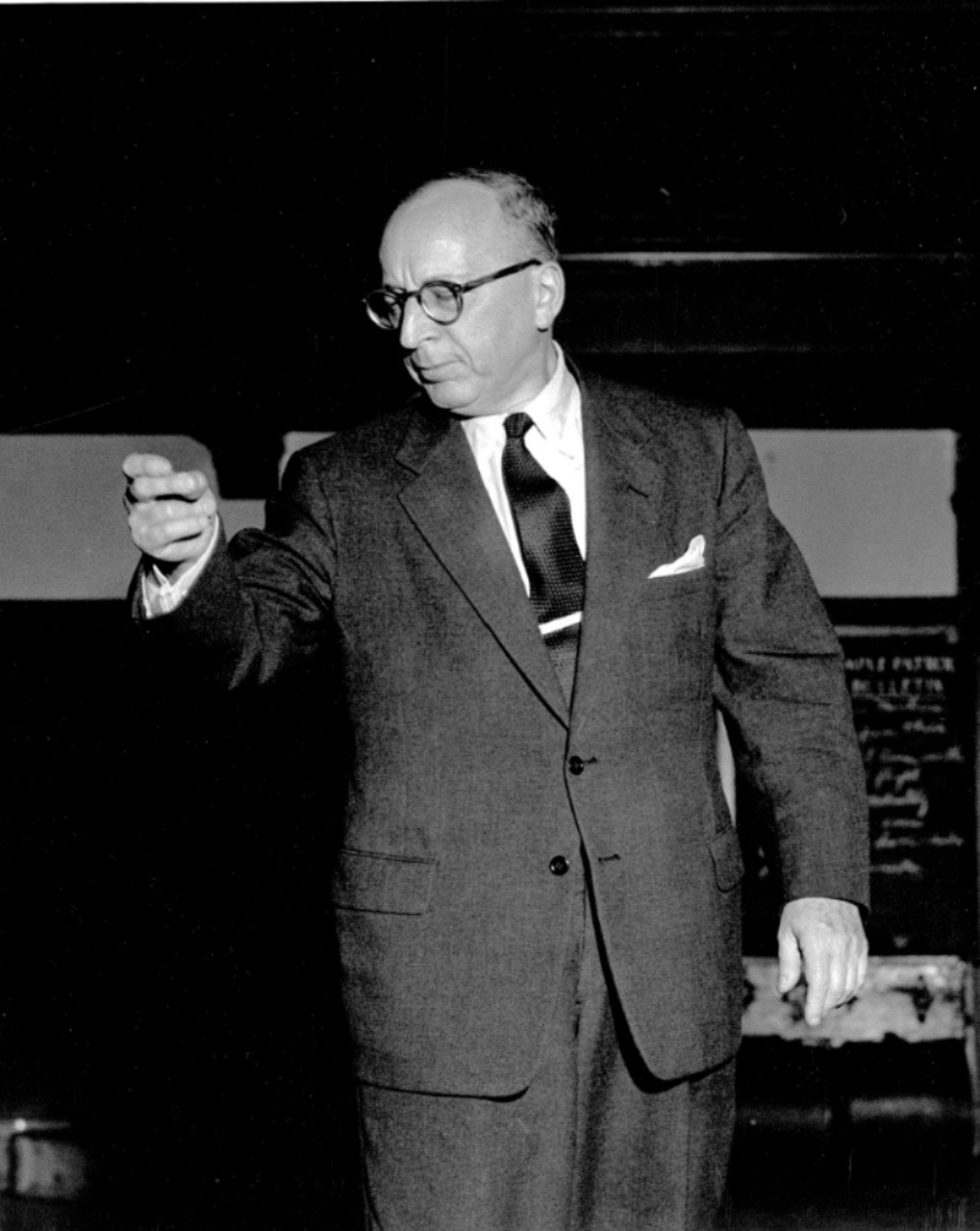

Alongside the scholars, a number of German-Jewish musicians also found work in Japan. Among them was the conductor and composer Klaus Pringsheim (1883–1972), brother-in-law of the writer Thomas Mann (1875–1955). Hired as professor of composition and counterpoint in 1931 at the Tokyo Music School (today Tokyo University of the Arts) on a two-year contract, Pringsheim remained there when the Nazis came to power in 1933, for returning to Germany was no longer possible. His contract was extended until 1937, but then allowed to lapse under pressure from the German embassy. After a year in Thailand, where he founded a music academy, he returned to Japan and survived the war years under precarious circumstances, giving private lessons to Japanese musicians. After the war, Pringsheim – by then over sixty – was unable to re-establish his career in either Europe or the United States. He eventually returned to Japan, where he secured a permanent position at the prestigious Musashino Academia Musicae (Musashino ongaku daigaku) in Tokyo, remaining in the country until his death.

Another was the Kraków-born, Vienna-trained conductor Joseph Rosenstock (1895–1985). Having conducted most recently for the Jüdischer Kulturbund in Berlin, he emigrated to Japan in 1936 to become conductor of the New Symphony Orchestra of Tokyo (Shin kōkyō gakudan), today’s NHK Symphony Orchestra. Rosenstock retained his post throughout the war, though he was evacuated to Karuizawa during the final months. After 1945, he continued his successful career in the United States. His nearly uninterrupted wartime position as conductor of one of Japan’s leading orchestras illustrates that Japanese authorities did not always yield to demands by local Nazi offices to dismiss Jewish musicians and scholars.

Numerous other German-Jewish musicians could be mentioned. Japan’s musical world, driven by its desire for Western expertise, benefited from these rigorously trained artists – largely irrespective of their religion or, in Nazi terminology, their ‘racial classification.’ Thus, in a sense, Japan benefited from this group’s forcible departure from Europe.

Fig. 7: The Vienna-trained conductor Joseph Rosenstock, 1955. Private collection. Courtesy of Thomas Pekar.

Overall, German-Jewish émigrés in Japan had to navigate very difficult circumstances. On one level, they were confronted by a formidable cultural barrier and language gap; most only learned very rudimentary Japanese. At the same time, they endured job insecurity and faced the constant threat of dismissal. Unlike most other countries of exile, Japan harbored a significant Nazi Party presence: local party branches, teachers’ organizations, and individual Nazi fanatics who made life difficult for the refugees. One notorious example was Walter Donat (1898–1970), ‘Cultural Commissioner’ of the NSDAP Local Group Tokyo–Yokohama, who personally intervened with the Ministry of Education (monbushō) against Jewish émigrés.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, spreading the war to the Pacific theater and drawing in the United States, further deepened the country’s alliance with Germany. The Tripartite Pact, signed in September 1940 by Japan, Italy, and Germany, formalized the so-called Axis of Berlin–Rome–Tokyo. As part of this pact, the ideological cooperation between Japan and Germany intensified. For Jews living in places under Japanese control, this meant they were confronted with an increase in official antisemitism where they lived and a corresponding deterioration of their living conditions.

This was compounded by the growing influence of German Nazi organizations. Beginning in 1933, Nazi activities had a palpable presence even in Japan. That year, a Tokyo–Yokohama Local Group of the Nazi Party was founded, and the group soon held regular indoctrination meetings. By degrees, the lives of the roughly 1,200 Germans living there were brought into line with Nazi ideology. The OAG lost its Jewish members, who were expelled or resigned. Other German institutions in Japan, such as the German School Association (Deutscher Schulverein), underwent the same process.

Antisemitism among Germans in Japan toward local German-speaking Jews became increasingly palpable in daily life. Beate Sirota Gordon (1923–2021), the daughter of pianist Leo Sirota (1885–1965) and later a noted women’s rights advocate and performing arts presenter, was forced to switch schools in 1938 due to growing antisemitic discrimination. Gordon had been attending the German School in Tokyo, which had very few Jewish students. (For instance, school records from 1937 mention a ‘Japanese-American-Jewish’ pupil named Franz Wertheimber [?–?].) By the time she left, the school had already adopted nationalist rituals such as the daily flag salute and a Nazi-aligned curriculum.

The appointment of SS Standartenführer Josef Meisinger (1899–1947) as police liaison officer and special representative of the Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers SS (SD) at the German Embassy in Tokyo in early 1941 marked another escalation. In addition to monitoring German émigrés in the country, Meisinger sought to prevail upon Japanese authorities to take harsher measures against the Jews in Shanghai, possibly even ‘recommending’ their mass murder, a proposal the authorities rejected.

In the decades following the war, Jewish themes played only a minor role in Japan, apart from an intense engagement with the Shoah that became closely linked to the story of Anne Frank (1929–1945). A Japanese translation of her diary – first published in Dutch in 1947 – appeared as early as 1952 and was widely read. The Holocaust Education Center near Hiroshima, founded in 1995, focuses on her life and those of other children and adolescents who were murdered in the Shoah. Likewise, the Tokyo Holocaust Education Resource Center, established in 1998, offers educational programs for Japanese schoolchildren. Neither institution, however, focuses on the history of German-Jewish émigrés in Japan. Japanese engagement with the Shoah often compares the mass murder and suffering of European Jews to the fate of the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki who were killed by US atomic bombs in August 1945.

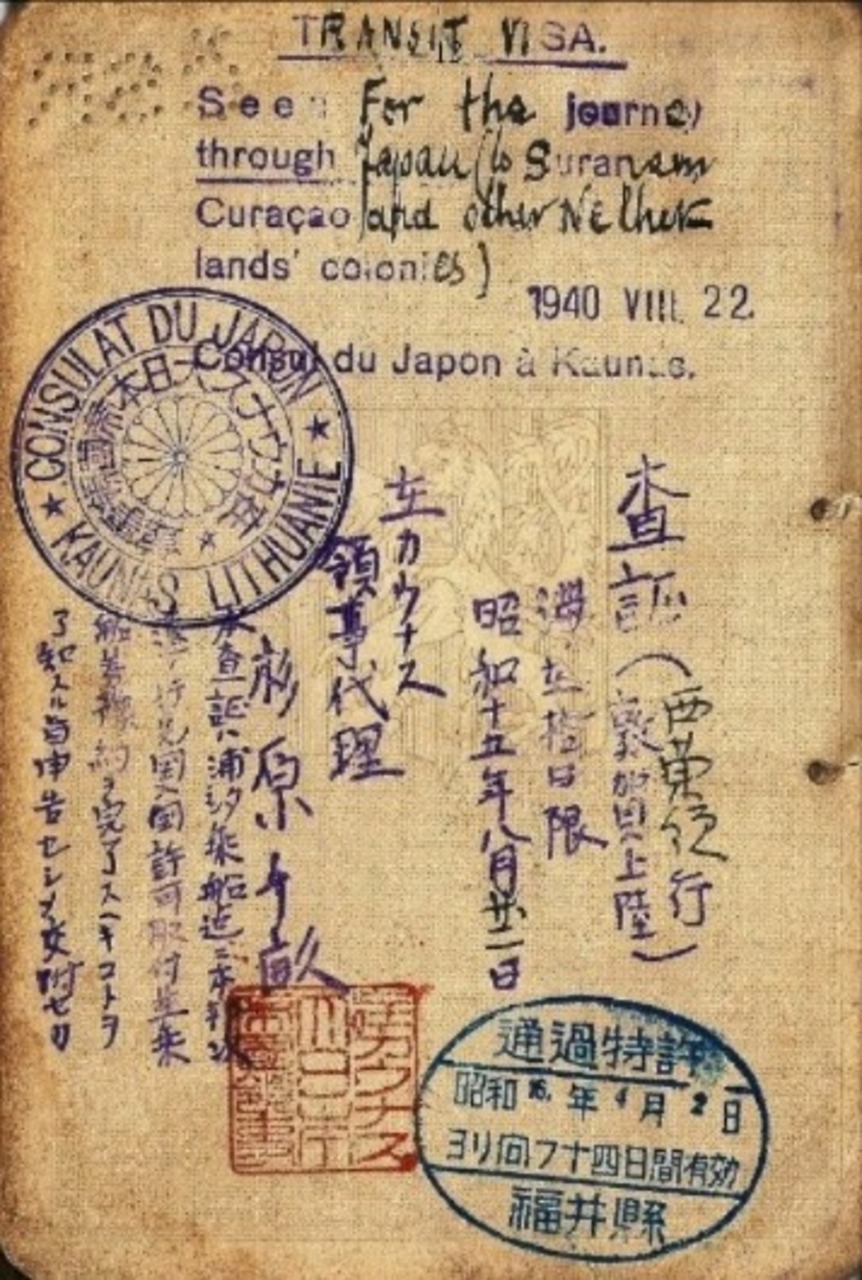

Recent years have seen the emergence of a new revisionist historical narrative that exploits the story of the diplomat Sugihara Chiune (1900–1986) for political purposes. As Japan’s vice-consul in Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1940, Sugihara issued between 2,000 and 6,000 transit visas – mainly to Polish Jews but also to roughly 200 German Jews – allowing them to travel through the Soviet Union to Japan, thereby escaping the Nazis. Today, some Japanese revisionists invoke his humanitarian actions to deflect attention from Japan’s own wartime atrocities, portraying them instead as evidence of the supposedly ‘humane’ side of the Japanese Empire during the war.

Fig. 8: Transit visa issued by Sugihara Chiune, 1940. Its holder had fled from Czechoslovakia through Poland to Lithuania. The visa permitted onward travel to Dutch colonies, including Suriname and Curaçao. Creative Commons license, Sugihara visa - File:Sugihara visa.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

Today, roughly 2,000 Jews – most of them foreign nationals – live in Japan, much as they did in the late nineteenth century when the country first opened to the world. They are generally perceived as part of the growing community of foreign-born residents rather than as a distinct religious or ethnic group. Jewish life is centered on three synagogues and Jewish Community Centers in Kobe and Tokyo, all served by rabbis from the US.

Whereas in the nineteenth century, German-speaking Jews – such as the merchants and businessmen Rubin Haskell Goldenberg and Sigmund David Lessner – once played leading roles in Japan’s early Jewish congregations, their presence today is negligible. The country’s Jewish communities are now primarily international and dominated by Americans.

In general, German-speaking Jews in Japan never formed a cohesive group. Before 1933, they were largely integrated into the wider German community, participating in its schools and associations, though not without encountering antisemitic prejudice. After the Nazi rise to power, they became increasingly isolated. A new wave of Jewish émigrés – almost all men and often highly accomplished scholars and musicians – joined them, having been invited by Japanese universities and cultural institutions to help raise the standards in scholarship and music. For many, Japan was a country of refuge whose hospitality spared them from being murdered in the Shoah. A few of these émigrés, such as Karl Löwith, Klaus Pringsheim, and Joseph Rosenstock, are still remembered in Japan today – not primarily as persecuted refugees, but as important intellectuals and artists.

We would like to thank Professor Kawashima Takashi (University of Kyoto, Japan Society for Jewish Studies in Kobe) for his generous assistance with the research for this article.

Jewish Community of Japan (JCC): https://jccjapan.jp/our-history/

Mara Weiss/Mitchell Bard, “Japan Virtual Jewish History Tour”, in: Jewish Virtual Library, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/japan-virtual-jewish-history-tour - google_vignette

“Jewish Settlement in the Empire of Japan”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_settlement_in_the_Japanese_Empire

“History of the Jews in Japan”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Japan

“History of the Jews in Japan”, film by History Media-HD, 2021: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6vnjyYzYvM

“About the Jewish Community of Kobe“, Jewish Community Chabad Kobe & Osaka, Japan (JCC): https://jewishkobeosaka.com/about-2/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Mechthild Duppel-Takayama holds a master’s degree in German studies and a doctorate in Japanese studies (Ph.D., thesis on Japanese Nobel Prize winner Kawabata Yasunari). Her research focuses on comparative literature and cultural studies. She has been in Tokyo since 1998, initially as a DAAD lecturer at Keio University, where she then served as an Associate Professor at the Institute of German Studies until 2012. From 2012 to 2024, she was a professor in the Department of German Literature at Sophia University and also taught in the Japanology program. Since her retirement, she has been a lecturer at Sophia University. Her publications include works on cultural contact, literary reception, and exile literature.

Thomas Pekar wrote his doctoral thesis on the Austrian writer Robert Musil; habilitation in modern German literature at the University of Munich with a study on the European reception of Japan. Scholarships and fellowships (including at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Historisches Kolleg in Munich), research projects, and teaching in Germany, Japan, South Korea, and the USA. DAAD lecturer at the University of Tokyo. Since 2001, he has been a professor of German literature and cultural studies at Gakushuin University in Tokyo. Research on exile literature, cultural contacts (especially Jewish exile in Asia), and classical modernist literature.

Mechthild Duppel-Takayama, Thomas Pekar, A Temporary Home: German-Speaking Jews in Japan (translated by Jake Schneider), in: (Hi)stories of the German-Jewish Diaspora, July 10, 2025. <https://diaspora.jewish-history-online.net/article/gjd:article-31> [February 17, 2026].